Many of you will have seen it before: a sappy-sweet film in which the Fresh Prince plays a down-on-his-luck entrepreneur, Chris Gardner, who is trying to provide a better life for himself and his son (a younger, less obnoxious Jaden Smith). By the end, through wits, determination, and a little bit of luck, he succeeds—obviously. The memory stayed with me, cast in glittering amber, unexamined; Will Smith was my Santa Claus.

The entire thesis of the film is that life’s present struggle is in service to a brighter future; when difficulties and stresses fade away in the warm glow of material success; life’s tensions resolved by the corporate ladder. There is no contentedness, only the climb.

But is that really ‘happyness’? The UN seems to think so.

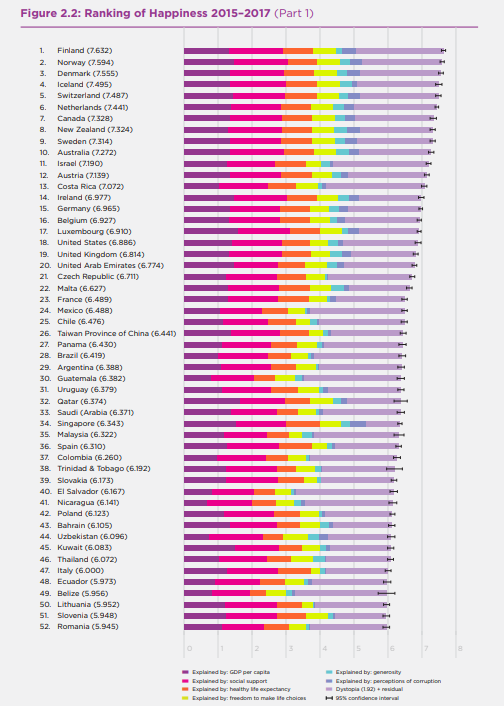

In March, the United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network released its World Happiness Report for 2018, ranking Singapore 34th out of all countries globally; 2nd in East Asia, behind Taiwan. Not bad; not bad at all. But if you look at the chart, some interesting details stand out.

Secondly, we see the numerous factors used to rate the top 52 countries: GDP per capita, social support, life expectancy, freedom, generosity, corruption, and lastly, dystopia. Wait, what? What does dystopia even mean?

Essentially, the report attempts to account for overall happiness (on a scale of 1-10) by approximating the contributions made by the first six factors. The last portion of each country’s happiness bar, appropriately coloured in mauve, is the ‘dystopia’ factor.

If a country’s hexa-colour-rainbow is very short, yet their happiness is high, the dystopia bar will be longer (i.e. more dystopic). Conversely, the shorter the dystopia bar, the more dystopic that country is, because they should be happier, based on the previous six factors, but they aren’t.

Simply put, ‘dystopia’ is just a placeholder term for whatever amorphous affects the researchers couldn’t account for with the other six factors.

Now back to the chart. If you notice, on the ‘total happiness’ bar (i.e, all seven factors), Singapore fits smoothly into the gentle slope of decreasing happiness. But if you limit your scope to the six measurable factors, you notice that Singapore’s bar is the largest, meaning that we should be the happiest — but we aren’t.

The most obvious reason for this is that, well, the grand total of six factors measured are pretty myopic. Like in Pursuit of Happyness, the myth of greater economic wealth-per-capita being able to purchase more happiness is, well, childish.

The problem of oversimplification applies to other factors as well. Having a longer life expectancy, such as living till 80 instead of 50, won’t leave you happier for having had eight miserable decades when compared to five good ones.

Those factors that do account for the more immaterial concerns are amorphous and notoriously tricky to measure. After all, does generosity account for competitiveness or performative kindness; does perceived corruption account for soft realities like social immobility?

But getting into the gunk of statistical theory and research methodology is besides the point. Perhaps the reason the study can account for so little in human ‘happiness’ is that its very foundations are flawed.

You see, the World Happiness Report uses a simple metric to ascertain the value of happiness for each individual surveyed, from each country. It takes the form of the Cantril Ladder survey, in which all participants are told to think of their lives as a ladder with ten rungs; the worst possible life being the first, and the best possible the tenth, closest to the sky. The surveyee is then asked: where do you stand?

And hence The Pursuit of Happyness comes into play. Have you fulfilled your potential? Have you hunted down that golden deer? Like the cover of a third-rate pop digest, the questionnaire screams “ARE YOU LIVING YOUR BEST LIFE?”

The problem with the literal ‘Pursuit Of Happyness’ is not the happyness, but the pursuing. And nobody knows that better than Singaporeans, living in our capitalist paradise (so conservative parties across the West view us), yet singularly un-satisfied.

The Pursuit of Happyness pitches life as a struggle for better—and it isn’t wrong. But perhaps in the framing of that question, as a ladder, measured up against infinite sky of possibility, the World Happiness Report has missed the essence of contentment.

I recall the zen-like stoicity of ‘Asian values’: the ability to live in the here and now, accepting it as our reality, even as we work to an improved one. To grow up, to give up on Santa Claus.

Ironically, by pursuing Happyness, through fleeting consumption and idle daydreams, we rob ourselves of the deeper appreciation of the present. Perhaps it is in the ability to inhabit the present moment, instead of slaving ourselves to an indeterminable future, that is the foundation of mental well-being, of contentment—of some actual ‘happiness’.