All images by Zachary Tang for RICE Media unless otherwise stated.

Not long after my child turned one, I realised I might have a problem with bus seats.

Whenever I have him in the baby carrier, his legs would rest naturally by my side. This means we would end up occupying 1.5 seats on board. On a bus during rush hour, you’d probably catch me tilting so my child’s leg would take up less of the adjoining space.

Sometimes, the closest standing person would smile and nod as I wiggle around to make space for another paying customer. “It’s okay,” they tell me.

Other times, passengers would squeeze through the crowd, eyes locked on the prized space beside me, only to find out the seat they coveted wasn’t that vacant. Cue an audible “tsk” and a roll of their eyes, followed by an awkward silence.

Look. It’s not that I haven’t tried looking for a solution. I could unbuckle the baby carrier after taking my seat. That is, if you don’t mind me fidgeting too much during a 10-minute-long journey.

But more often than not, I just stick to standing up. After all, I still have a diaper bag slung over my shoulder.

I can’t juggle everything on a moving bus. I’m a mum, not an octopus.

How Wide Are Our Bus Seats?

I wonder if it’s just me or if the problem lies in the size of the bus seats.

I emailed the Land Transport Authority (LTA) and told them my dilemma. They were empathetic and informed me that the average public bus seats are 42cm wide.

This is “sufficient for each passenger,” a representative replied.

I’m unconvinced. One day, I decided to measure the width of the bus seat on my way home. It was 37.5cm—the mystery deepens.

“I know your pain. When I was in design school, I’d always struggle to carry my bag, laptop, and all the needed materials while staying within the seat,” Larissa, a client service executive shares. She’s not a mother, but she is the nearest person I can vent to.

As an adult, Larissa still finds herself struggling to hold onto all her personal belongings and shopping bags while the person sitting beside her fidgets and tries to create more personal space.

“I tense my legs all the time when I sit on the outer seat,” she continues. “Once, my head was hit by another passenger’s shopping bag. I didn’t want to get into a dispute so I just tolerated it in silence.”

Even though what Larrisa and I had experienced might be unique, you probably would have noticed some of these behaviours on your bus commutes too.

There’s also that nagging problem of commuters refusing to sit on certain seats in the bus—specifically the middle, rear-facing, or at the back. The Bermuda Triangle of bus seats, if you may.

Still, the explanation behind why people avoid those seats isn’t that mysterious. Those seats are just inconvenient to get out of in the shortest time possible. We’re an efficient nation, alright—right down to seat choice.

On social media, some have questioned the practicality of these seat designs, perplexed at the odd hand grip pole that often blocks a clear path to the seats.

A man tried explaining why he needed to spread his legs and how he approached the situation politely on a bus. He raises valid reasons—height and heat discomfort in the nether regions.

Others, like AMC, took to the good old digital publishing to voice his displeasure.

The Bus Capacity Conspiracy

AMC is a bus enthusiast and founder of the blog SG Transport Critics. In an entry in July 2020, he tried to address a similar query: Seat arrangements and capacity of our local buses.

His motivation for writing it surfaced when he came across some heated debates among commuters on an online forum about why certain bus models can carry more passengers than others.

This prompted him to compare the capacities of the two most common single-deck bus models in Singapore: Mercedes-Benz Citaro and Scania K230UB.

At present, all four local bus operators—SBS Transit, Go Ahead, Tower Transit, and SMRT—deploy about 1155 Mercedes-Benz Citaro across their serviced routes.

SBS, on the other hand, is the only bus operator that has around 1,000 Scania K230UB in its fleet.

Mercedes-Benz claims the Citaro can carry more passengers (90, both seated and standing) than the Scania (88, both seated and standing) and is able to accommodate up to 65 standees.

AMC found the numbers highly dubious and questioned if it works in practice. “I think those numbers can only fit in a perfect world,” he says.

“It’s a world where passengers travel empty-handed, and are very willing to move to the back of a bus to utilise every inch of the floor space.”

AMC suspects there could be severe number-fudging involved just so that Mercedes-Benz Citaro can dominate the transit bus market here and abroad.

Indeed, the Citaro is one of the most widespread public bus models in Europe, even though Singapore is the only city in Asia that uses it in its public transport system.

A Sitting Person = More Space

But to wrap one’s head around seating capacity, it’s important to know how bus seats are designed within the space.

To make room for more passengers, seats on public transport are arranged longitudinally. “It’s like what you see on the MRT where the seats are along both sides of the train,” AMC explains.

“Buses, like the Mercedes-Benz Citaro, however, use a latitudinal seating arrangement, where the seats are perpendicular to the length of the vehicle.”

That’s why AMC presumably thought the Mercedes-Benz Citaro had a lower passenger capacity.

Remember, latitudinal > longitudinal.

“The Scania K230UB buses use longitudinal seating at the front half to create more standing space. By logic, it would have more capacity than the Citaro,” AMC rationalises. “Now, you understand my doubt?”

I suppose companies have a valid reason to want to maximise space in their buses or give the impression of roominess. Manufacturers design their products (in this case, buses) in a way that will drive profits and sustainability.

Also, Mercedes-Benz and Scania are not local manufacturers. In fact, Mercedes-Benz shipped their completely built-up Citaro buses from Germany, while parts of Scania buses were assembled in Malaysia.

How, then, do these companies determine or even modify the blueprint of their buses to fit our local context and commuter patterns?

The Golden 42cm

Primarily, bus seats are designed and arranged to provide sufficient room for the bus engine.

Unfortunately, our current technology is unable to reduce the size of the engine. Hence, the bus floor is slightly raised, and we need to walk up a step or two to arrive at our seats.

Still, I’d like to know why 42cm was chosen to be the width of our bus seats.

I emailed five manufacturers with buses currently deployed in our local public bus service.

Initially, Mercedes-Benz was very forthcoming with replies. They stopped replying when I told them about the bus capacity discrepancy highlighted by AMC and asked for a brief history of their partnership with local bus operators.

Volvo Group, the manufacturer of 1,600 double-decker Volvo B9TL buses in Singapore, said they are “not in the right position to reveal and comment”. These buses are “currently LTA’s assets”, so I should ask LTA instead.

Alexander Dennies Limited (ADL), manufacturer of the latest three-door double-decker buses said, “our buses are always tailored for local operating conditions, so there is no standard international design.

“All parts including seats are chosen to best respond to the requirements of our customers as expressed in their tender processes.”

Bus Model vs Bus Seat Model

I shared my bus seat and bus capacity queries with bus enthusiast and Youtuber Maxson Goh and asked for his thoughts.

He politely told me that I might be going about it the wrong way. Bus seats are produced by entirely different manufacturers from the bus frame itself.

Maxson loves investigating buses—his word is authority. Last August, he made a video to rank the best bus seats in Singapore. He mentions that there are five types of bus seat models used across all bus models in Singapore.

Two of them, including the most common Vogelsitze System 750/3, can be traced back to the same German company, Vogel Holding. Again, I tried getting in touch.

As the company is not represented in Singapore, I reached out to the Vogelsitze regional offices in Korea, Hong Kong and Vogel Industries in Malaysia, but there was no reply from them either.

At the same time, I consult an ergonomic expert who can shed some light on the anthropological aspect of my investigation.

There is a facet of anthropology known as anthropometry that influences the design of public space and the equipment we use at work, and in turn, their efficiency and lifespan.

Anthropometry is the measurement of different parts of our bodies and their corresponding proportions. Even within the same country, anthropometric data can be rather diverse as it changes with age, gender, and nutrition.

The Human Factor

Obviously, anthropometric data impacts the design of public spaces, particularly bus seats.

To do that, I contacted Associate Professor Chen Chun-Hsien, Director of Design Stream and Professor-in-Charge of the Design & Human Factor Lab at Nanyang Technological University (NTU).

He published a paper in 2019 documenting the anthropometric measurement of adult Singaporeans.

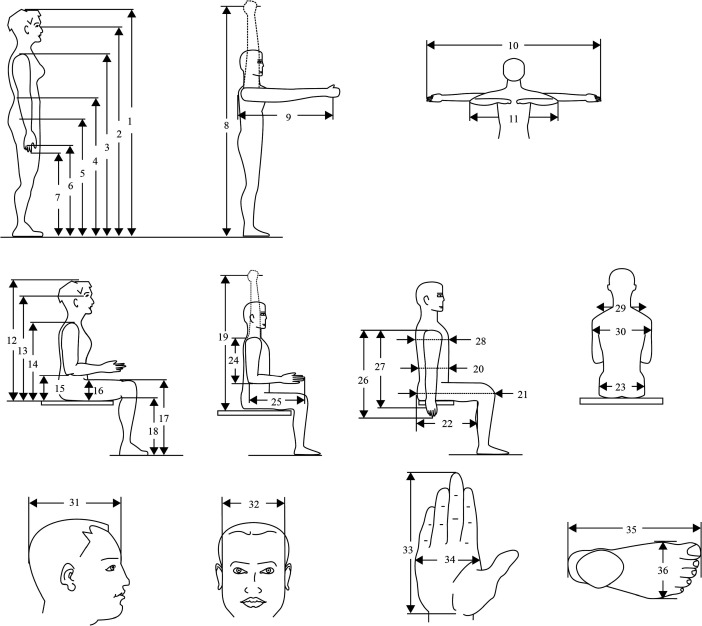

Even though the measurements are not representative of our multiracial population, Professor Chen found that the average hip breadth (point 23 on the above diagram) or the widest proportion of the hip for men is 31.5cm. For women, it’s 30.5cm.

The maximum horizontal breadth (point 30 on the same diagram) across our shoulders is 44.9cm for men and 39.8cm for women.

I am targeting these two measurements because we are most likely to bump into the person sitting next to us with our hips or arms.

So if 42cm is truly the “golden number” for our bus seats, it may be a little small for some of us. Professor Chen recorded individuals with horizontal breadths of 50.2cm.

I needed more data, so I got in touch with Alex Lee, a senior ergonomics specialist at local ergonomic consultancy Synergo. Synergo offers design advice, training, and product reviews for companies in need of better office setups or workstations.

Interestingly, SBS Transit was one of Synergo’s clients.

Alex tells me that both the width of our hips and shoulders are important criteria to consider when it comes to the design of a seat.

“Nevertheless,” he adds, “there is a lack of ‘individual adjustability’ in public space. This means designers have to compromise their designs for a broad range of people. In this case, taller or stout individuals may feel insufficiently supported when sitting in ‘average’ seats.”

Alex notes most often, seat depth is adjusted to fit more people into a public space. Likewise, armrests are omitted in the name of space—bad news for the elderly who can lean on them to push themselves up from a seated position.

Ideally, as Alex suggests, a seat width should be slightly wider than our hips for comfort.

Our shoulder width can also be used to determine the size of the backrest and guide the space between us and the adjacent seated person.

“This is to avoid a commonly-faced situation where your arms or elbows bump into the person sitting next to you,” he adds.

Into The Thick of Measuring

While anthropometric data should be used as much as possible when it comes to design, it’s not always available or updated as physiques change with every generation.

What Alex observes: People are generally getting bigger in size.

Just to be sure, I went on a bus seat measuring spree with AMC and Lemonnarc, co-author of SG Transport Critics.

It turned out that only the seats on the Mercedes-Benz Citaro are 42cm wide—the rest are slightly narrower than 42cm. To our surprise, one of the seat models is 43.5cm wide.

I learnt a lot from writing this article and going for a measuring spree with AMC and Lemonnarc. I can also finally let go of that lingering feeling that I am creating drama out of nothing.

“I think there’s just not enough public awareness on public transport-related issues,” Lemonnarc notes.

“Most of the time, we are too eager to blame someone—those who refuse to move to the back of the bus, take up certain seats, or carry too many things with them on board—without looking at a bigger picture or even the root cause of the problem.”

Unsurprisingly, the topic of public bus seats is often overlooked. And why would we pay attention to the size of where we sit? We tend to focus our attention and resources on public transport services, fares, and the duration of bus journeys. On top of STOMP-worthy shenanigans that occur on bus rides.

Like everyone else who has, in one way or another, shared their frustrations about bus seats or bus designs, I believe we’re not looking for an immediate actionable solution here.

We just hope our experiences would open a door to understanding what goes on behind the scenes and what considerations are taken into the design of public transportation.

As for the rest of our commuting annoyances, I guess it’s all up to us. Like LTA’s reply to my concern, “In promoting gracious community, our commuters would understand such situations.”

My child graduates from the baby carrier shortly before his second birthday. Now, I look forward to the day when he arms himself with a child concession card and openly occupies a seat beside me.

Till then, here’s hoping LTA and the Public Transport Council will not only review our public transport fares but also the capacity and comfort level of our transit—and whether what we’re paying for is worthwhile.