Photos by Stephanie Lee and Zachary Tang for RICE Media.

What makes a loveable city?

If you were to ask me, a loveable city–in which case, Singapore–is one where the relationships I hold, the food I enjoy, the buildings I admire, and the life I live are moulded by my community. The people closest to me, the people surrounding me on trains and in the office–you get the idea.

Not all of us have the privilege of defining our own lives in an overwhelmingly busy city. Some find a rhythm to follow–all the more why residents in neighbourhoods like Pasir Ris, Potong Pasir, or Yishun attest to their own unique way of living.

A loveable city can be a city where you may overlook its flaws, or simply embrace them as part of its character. A loveable city can also be a city that you love with all its flaws, while imagining a better one down the road–one where every resident can find something to love, and to feel loved.

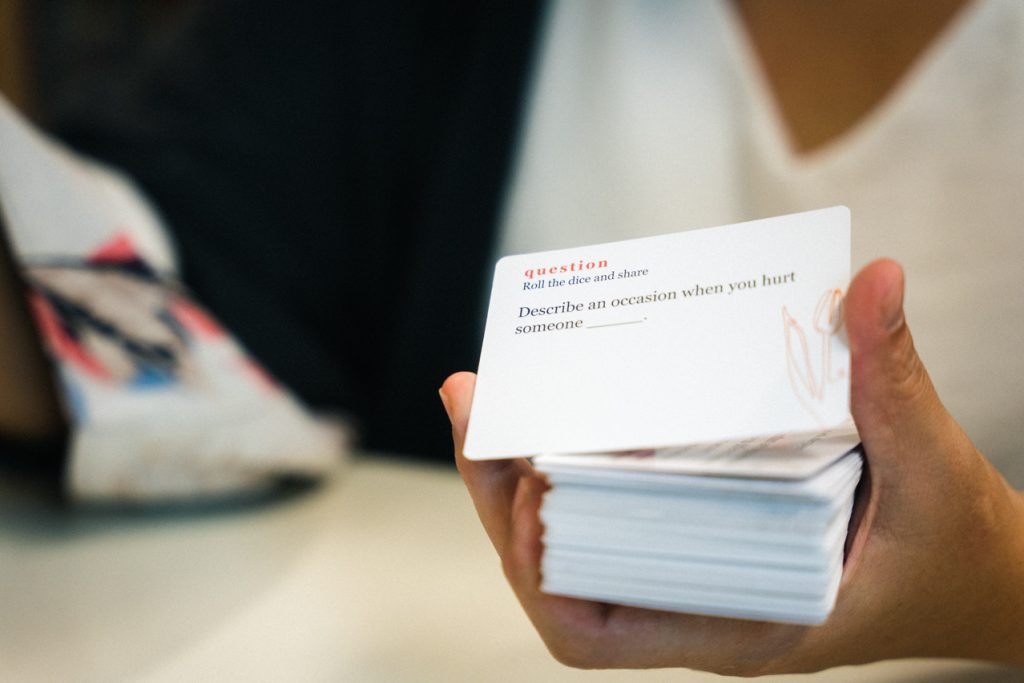

Not all of us have the tools to make that change. But for the ones who do, the hard work is worth it. Take for example, Trecia Lim, whose card game Hello Empathy seeks to build bridges between people. Her idea of a loveable city begins with communication.

In This Game, Everyone’s a Winner

If Trecia Lim’s project ‘Hello Empathy’ doesn’t already indicate what it’s about, let’s just say that it’s the kind of game that wouldn’t result in any feuds or intense competition.

“This game was designed for people with special needs in mind,” says Trecia. “In this case, we focused on the autism community.”

Trecia is an architect by trade, which makes her debut in card gaming all the more fascinating.

“As an architect and designer, I found something missing in both worlds,” she says. It’s consideration for people with special needs, she adds, which she has found limited to physical access: wheelchair ramps, lifts, and so on.

“There are different kinds of disabilities that we need to be aware of,” she states. She and her team at WeCreate Studio knew there was an inclusivity gap – she just didn’t know what it was, let alone realizing it could come in the form of a card game.

Supported by the Good Design Research Grant from the DesignSingapore Council, Trecia and her team spent a year devising a framework that would generate a form of spatial design – that is, the integration of architecture, landscape design, interior design – catered to the needs of people with autism.

“While we had that in mind,” Trecia adds, “we also wanted to create something that would include use by a broader community. We started this journey ourselves to learn deeply.”

It meant a product that would reflect the experiences of people with autism – a highly specific group – as it integrates teachable elements that would introduce other players to a life lived with autism. Hello empathy, indeed.

Trecia found a card game was most suited to the task. “Everyone can engage with it without any barriers,” she says. “We found that the game allows you to learn from each other.” There’s no competition here.

Goodbye Exclusion

Trecia and her team started volunteering at St. Andrew’s Autism Centre, where she watched students interact with each other–playing with LEGO bricks, sketching on paper, spending time by themselves. They weren’t the most social bunch, she observed, but she realized how, in their own way, they were able to express themselves creatively when she tried talking to them.

“I think a lot of meaningful interaction is about really letting go of social barriers,” she noted, “To put aside what you think you know. To listen, to converse, to want to take away something from the conversation because of the other person.”

Her understanding of social interaction through the lens of autism deepened when she spoke with specialized educators, designers, social service agencies, and parents of kids with autism.

“Empathy is a big word,” she explains the game’s title. “It embraces both the positive and negative aspects of a condition.” Each card presents a way for two players to interact, with distinct instructions denoting a ‘Scenario’, which requires answering a question with the other player, a ‘Fact’, which simply means the player shares something interesting from the card to each other, or other cards like ‘Opportunity’, ‘Checkpoint’, ‘Task’, and ‘Question’.

It’s the art of conversational dynamics that many of us have learned through social conditioning over the decades, but it’s outlined with great clarity here. The game demonstrates to players how people with autism see something we take for granted – socializing – as a careful, sometimes complex, process.

WeCreate Studio’s pursuit of contributing towards a more caring, empathetic society didn’t stop when the cards were packaged for sale. Trecia intends to organize quarterly gameplay sessions for corporate clients, students, and the wider public.

She hopes as more people play the game, they “use the knowledge from it to bring about change in the diversity of social needs” and build towards a city that’s loveable for all.

Beyond that, a loveable city can also be defined by its buildings, as I later found out.

Strata Strains

Calvin Chua recently wrapped up an exhibition at The Projector, which ran for a week last March. It’s about the malls of a future Singapore, and how they might look like.

As you would already know, The Projector is located in Golden Mile Tower, a long-running building whose spark might be extinguished soon. Its sister complex is already earmarked for redevelopment in May.

Calvin’s work with his studio, Spatial Anatomy, has dealt with regeneration strategies–ways to think of existing cities and how they can be improved or redesigned for a growing population.

At the heart of this ongoing pursuit is an interest in expanding our horizons as a country.

“We look at our projects in a multifaceted way,” Calvin explains. “Every single project is a continuation of the previous one. This project is an extension of our past exhibitions.”

It started as casual research stemmed from an interest in the conservation of Singaporean buildings, particularly strata malls–think Queenstown Shopping Centre, Beauty World Centre and, of course, Golden Mile Tower itself.

From exhibition to panel, media interview to artist residency, the topic has followed Calvin and Spatial Anatomy over the past few years, ever since his studio was founded in 2016.

Once they received the grant under Good Design Research, however, they realized what their research had been missing. “For strata malls, the issue is beyond design or architecture,” he explained. “We realized there’s something more systemic that needs to be tackled with [public] policies.”

Unlike the current crop of modern shopping malls operating around Singapore, strata malls–which were introduced to Singaporeans in the 1960s–are populated by small, homegrown businesses, many of whom have operated for decades and are still run by its original owners.

These malls harbour their own legacies. Each time one of them gets the en bloc chop, the ensuing outcry demonstrates the deep connections Singaporeans have with them.

Calvin wants to preserve every strata mall we have–he recognizes the attachment several communities and shopowners have with these buildings, and each tell a history of Singapore that stretches back decades. For some Singaporeans, that history goes hand-in-hand with their own connection with Singapore.

With land scarcity around us being an evergreen issue, he seeks to challenge our attachment with the act of preservation. “If the mall can be saved, it can be rejuvenated,” he explains. “But if it can’t be rejuvenated, how can we allow for its graceful decommissioning?”

Bukit Decentraland Ave 3

In Calvin’s case, graceful is relative – the landscape of Web3, the virtual playground of billionaires and day-and-night hustlers that’s also known as the metaverse, is one that’s akin to a modern wild west. While some bristle at the idea of adapting to a newfangled environment designed by tech-industry moguls, others find sincere potential.

Calvin believes that’s where communities from old strata malls can continue to exist. “Can the existing shop owners of strata malls be ‘transferred’ to a virtual entity? Can we use these virtual platforms to redefine local communities?” He evokes the use of the word ‘spirit’ to quantify the deep meaning each mall may have to communities.

“It’s an interesting discourse to talk about saving a building, but also letting go of its spirit,” he mentions, referring to the impending redevelopment of Golden Mile Complex, which will displace several businesses that have catered to a Thai-speaking segment of Singapore’s population.

For Spatial Anatomy’s research, they used Beauty World Centre as a case study by bringing it into the metaverse as a virtual museum. “We wanted to try bringing back the “old” Beauty World, with some of the artefacts of the shophouses, the performance theatre, the Tua Pek Kong Temple,” he says, “so that visitors can have a new experience of an old building and what it was like back then.”

Like many people, Calvin is still understanding the Web3 space. “It’s still very young, and its current existence is not very inclusive,” he confesses, alluding to the tech needed to access it and, not to mention, the integration of crypto coins, which has still proven to be a volatile currency.

But he adds that Decentraland, the metaverse platform that Spatial Anatomy’s project is based on, has the right tools for this – to explore how the legacy of strata malls can be retained in an ever-changing Singaporean society, where the past and present can, hopefully, co-exist, and different generations can love a city, even as it goes through changes.

To Be Loveable is to Look Inward

The Loveable Singapore project by the DesignSingapore Council Study discovered that initiatives which foster better social interactions and demonstrate care for others, similar to Calvin’s and Trecia’s projects, can amplify people’s sense of belonging and attachment to their community.

“Cities can take concrete steps to embody elements of a “loveable” city, helping their residents feel more connected, grounded and motivated to work hard for their city,” writes Duleesha

Kulasooriya, Managing Director at Deloitte Center for the Edge in the study’s forward. “The payoff: happier, more resilient citizens poised to drive economic growth.”

These initiatives have the potential to create a more loveable and livable Singapore–by encouraging the ties we have with our communities, and fostering connection through social relations, the robust possibility of a loveable city continues to grow.

According to the study, which gathered responses from various Singaporean residents, a loveable city can be defined by these emotional bonds: a sense of inclusion, attachment, connection, attraction, agency, and freedom.

“Designing a loveable city means being able to empathize with the people, and the communities that you’re designing for,” Calvin says.

“It’s challenging for designers to adopt that because it’s not taught in schools. I think more can be done to nurture designers who can ground their work in empathy.”

What informs Calvin’s work are the countless conversations he has with shopkeepers – the people who have invested most in these buildings that could be torn down in a moments’ notice.

He pushes forward in his work because he wants to establish a form of dignity that all Singaporeans should be entitled to: the dignity of a legacy, one that future generations can learn from, and parse through the passionate work and affection that has built Singapore into what it is today, and what it can be tomorrow.

Trecia hopes for a loveable Singapore that is embodied by a deeper form of mindfulness that encourages everyone to look inward.

“Each person’s [capacity for] empathy is defined by self-reflection,” she adds. “How much space do we have for the differences between us? And what are we going to do about it?” She sees it as an ongoing process of finding the right tools to understand each other to create a more empathetic and loveable country. Hello Empathy is just one of them.

“That’s the biggest step. We talk a lot, but we have not done enough yet.”