All images by Xue Qi Ow Yeong for RICE Media.

On the way to the Mormon Church, I prayed that no one would broach a polarising topic like “Golan Heights” or “that drag queen last supper”. I’m sure some faith leaders who were on their way to this Interfaith Durian Party had beseeched their respective Gods to implore this too.

In Singapore, racially-charged altercations still pop up in the news every now and then and tend to garner racially-charged responses. It takes just one errant remark to spoil a nice party, especially in this era where many of us have taken clear ideological sides on imminent global issues.

Would we enjoy a convivial time today? The odds were not in my favour at this durian party because people from over 20 different religious organisations would be in attendance.

Even though Singapore is years removed from the race riots of 1964 and 1969, to quote Taylor Swift, are we out of the woods yet? Are we in the clear?

Apparently not. Senior Minister Lee Hsien Loong had just told The Straits Times last week, “[Racial and religious] matters, in my view, will never cease to be sensitive.”

SM Lee is correct that religious harmony isn’t a cakewalk, but if only there was a simple solution to making it less like walking on eggshells. While we might look to policymakers and sociologists for answers, the Mormons are addressing this prickly problem with durians.

Durian Diplomacy

I step inside the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints for the first time. Its halls have a calming silence; its members greeted me with kind smiles.

I always walk by this domineering Neo-Renaissance building when I walk from Newton MRT station to a Thai disco in Balmoral Plaza. Devotees have been worshipping at this church along Bukit Timah Road since 1970. I would have to pass these eclectic landmarks—this vermillion church, then a nursing home, then a preschool, before I hear the woofing bass from said Thai disco.

I learned from these Mormons that their church has around 3,000 Singaporean members. who are involved in community projects like food banks and housing projects for the less fortunate.

Most people refer to them as ‘Mormons’, but they prefer to be called ‘Latter-day Saints’. I expected to meet Latter-day Saints in ironed short-sleeve shirts and ties, but was instead greeted by Saints dressed in colourful blouses, T-shirts and button-downs. They look as Singaporean as you and me—if you passed one devotee along the aisles of NTUC FairPrice, you wouldn’t do a double take.

They accompany me along walkways with warm lighting and ruby red carpeting decorated with classic Mormon art, which you might have seen in the Book of Mormon found in the bedside tables of some hotels. We took a lift to a hall where they held their services, which was transformed today into the venue of our Interfaith Durian Party.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints organised this Interfaith Community Party in collaboration with the Moulmein-Cairnhill and Sengkang Central Harmony Circles, organisations founded by the government to promote racial and religious harmony in Singapore.

Harmony Circles organise many intercultural gatherings throughout the year, and the Latter-day Saints of Singapore have been holding this durian party every two years or so. Their debut interfaith durian party in 2016 received such positive feedback that the Latter-day Saints held it in 2022 again and decided to make it a tradition.

I expected to see faith leaders with Jainist muhapatti masks, Orthodox kalimavkion hats and Taoist horsetail whisks in the party venue, but the various faith representatives in attendance all looked as Singaporean as co-commuters in your MRT cabin.

En-durian Religious Harmony

When the Latter-day Saints carried the eagerly anticipated durians—290 kilograms at that—into the hall, this haymaker of fragrant ammonia immediately created a new core memory in my brain.

Community leaders like Minister of State Alvin Tan and Sengkang Central Grassroots Adviser Dr Elmie Nekmat delivered speeches as we tucked into the durians.

What’s the connection between faith and durian? Is our shared love for durian the fruity key to enduring religious harmony? This contentious fruit is playing the common ground between Singaporeans from varying backgrounds as they talk about the similarities between their faiths.

While some might focus on the many religious wars in history, Dr Foo Check Woo, a man in his 60s, points out that ancient civilisations of various faiths had collaborated closely to develop sciences like medicine and geometry.

The most boisterous diner at my table, Dr Foo has been active in inter-faith work for the past 30 years, spurred on by the Baha’i faith’s teaching of respecting all religions. He’s a practitioner of the Baha’i faith who converted to Bahaism after he met his Persian wife. He has expounded on Bahaism in many religious dialogues.

As we listened intently to Dr Foo, the heady fragrance of durian remained at the fore, mingling with the ambient chatter and the occasional burst of laughter. The vibrant yellow of the fruit stood out against the pastel-checkered tabletops. It’s a festive atmosphere.

Diners of different faiths praise the persistent sweetness and thick aroma of the durians. Moreover, they were pushing the beloved fruit towards one another and encouraging others to eat more—an action understood in high context Asian culture as an act of love.

“Religions like Islam, Buddhism, Christianity, Zoroastrianism and Bahaism developed side by side over the centuries,” Dr Foo shares.

Our conversations about religion soon digressed to archetypal Singaporean topics.

I catch wind of remarks that ricocheted around the jovial room. “I’m travelling back to Hainan Island soon because my wife works there”, and “If you visit me in Balestier, you’ll see it’s a very modern neighbourhood now”, as strangers enthusiastically got to know one another.

As we licked the durian custard off our fingers and lost ourselves in engrossing conversations, we connected as humans with similar interests, plans, needs and desires. The differences in our religious beliefs took a back seat, as they should.

A Fruitful Party

The purpose of the Interfaith Durian Party was to foster friendships between people of different backgrounds, and these people were indeed whipping out their phones to exchange contact information.

In a world increasingly divided by differences, this durian party was a microcosm of what we can achieve when we focus on our common humanity. How can we replicate the unity fostered within this microcosm on a national or global scale? It was a reminder that beneath our diverse credos and practices, we all seek connection and understanding.

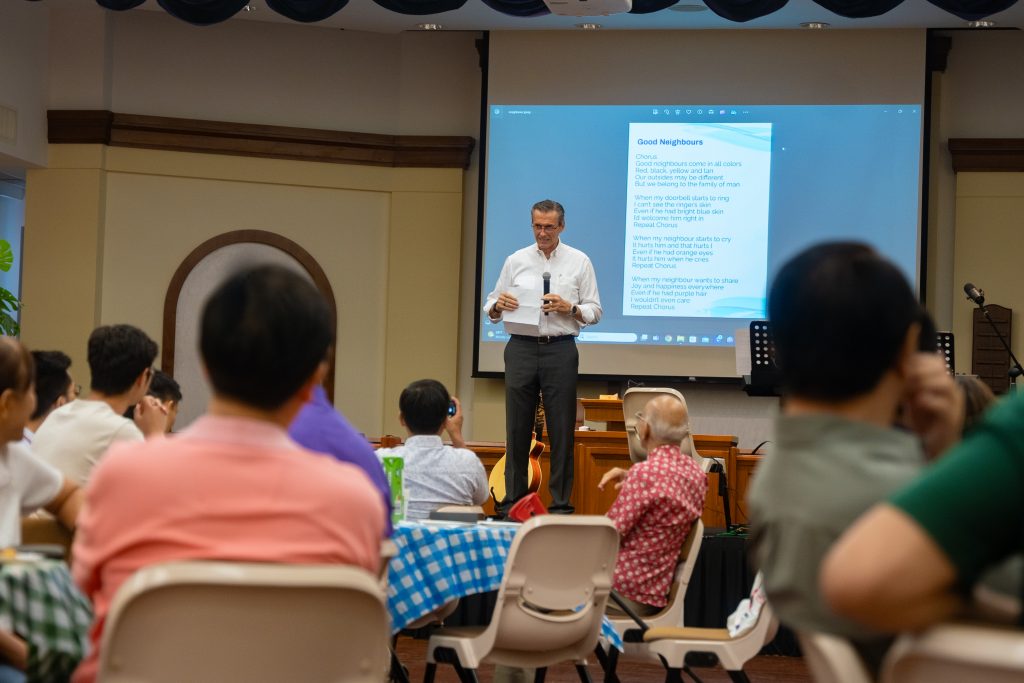

Indian dancers twirled their sarees and faith leaders crooned heartwarming songs about kinship, including Dr Foo with his infectious smile. As we savoured the rich, creamy flesh of the durian, the pungent aroma seemed to dissolve barriers, allowing us to engage on a genuine and intimate level.

“Many of us have been looking forward to this durian party,” said Latter-day Saint Lavon Lew, 47. “At my table, we weren’t asking about each other’s faiths. We were just having a nice time, drawn together by durian.”

“I thought this party would have attracted even more Singaporeans to attend, considering that durian was the lubricant,” said Dr Foo.

The good doctor is on to something. Attendees were happy and engaged, and the durian cream on our fingers minimised our screen time.

A Different Kind of Social Lubricant

Given the many different dietary restrictions of various religions, durian was a good choice of food to serve at this Interfaith Community Party, especially because it targets the Singaporean soul.

However, this party on Saturday still required compromise. I spoke with Seventh-Day Adventists, who had to rush over from their religious service because their branch of Christianity believes in worshipping on Saturdays.

“I’m very happy to see Singaporeans of different religions coming together,” said Latter-day Saints Elder Jean-Luc Butel, 67. Jean-Luc is a Caucasian Singaporean who was born in France and has lived in the United States.

“Very few countries are able to achieve religious harmony like this.”

The next time a thorny issue pierces Singapore’s inter-religious fabric, perhaps we could just hold another durian party?

After several rounds of durian were served, the emcee announced that Mao Shan Wang would be distributed next, and the crowd roared with elation. Singaporeans spend large sums on Mao Shan Wang, widely regarded as the finest durian for its buttery consistency and complex sweet-bitter flavour.

While Singapore is home to a diverse array of ethnic groups, cultures and religions, perhaps what Singaporeans have in common is our veneration of durian. Or at least most of us.

As for the Singaporeans who dislike durian, they make the effort to tolerate the smell of durian and circumvent this acrid fruit. They don’t usually start arguments with durian lovers, nor do they draw societal lines to segregate durian lovers from durian loathers.

Likewise, durian lovers don’t force durians down others’ throats or shout about how non-durian eaters are wrong. As it should be for religion.