All photos and videos by Marc Clarence Beraquit for RICE Media unless otherwise stated

The first time I encountered an Uncle Raymond clip on TikTok, I swiped it away. Nothing could convince me to endure a 15-second video of a wiry man in his 60s dancing to a Chinese song in front of Ang Mo Kio MRT station.

Sure, this bald man decked in a red polo shirt isn’t your run-of-the-mill TikTok influencer. That intrigued me. But nothing else about his videos did. I must have poor taste because the Uncle Raymond phenomenon caught on with Singaporeans.

Seemingly of mysterious origins, his dance videos popped out of nowhere and made their rounds on Singapore’s TikTok feeds.

His online presence is so ubiquitous that I struggle to recall a time on TikTok pre-Uncle Raymond. It was as if he simply decided to be TikTok famous one day.

He did. And as his videos became more popular on TikTok, so did the unsettling nature of his video formats. Something was amiss, and I couldn’t quite put my finger on it.

Everybody Loves Uncle Raymond

The premise of Uncle Raymond’s early videos is simple. MRT train station entrances form backdrops to his videos. It’s always the same dance set to a remix of Faye Wang’s ‘A Century of Solitude’.

The dance, I am told, was choreographed by Uncle Raymond himself and looks like it was inspired by martial arts. It begins with a series of three poses; the last of the three leads into a Hadouken-like dance move before it builds further momentum and crescendos in a jump, arms outstretched.

The man is ballsy, I’ll give him that. Even Gen Z TikTok natives scan their surroundings for prying eyes before filming a video. But he simply goes for it without giving a second thought to inquisitive looks and sly smirks from people around him.

At the peak of Uncle Raymond’s powers, the algorithm surfaced his videos once every hour, at least for me. And as the videos went on, Uncle Raymond’s solo act gained a following—in a digital and physical sense. On TikTok, Uncle Raymond commands a following of over 100,000. In real life, his most ardent supporters follow him to different locations to meet and dance with him.

Soon, these followers became staples of his videos, essentially turning into his background dancers. So much so that TikTokkers call them Uncle Raymond’s ‘interns’. As if by osmosis, as if by mere proximity, Uncle Raymond’s fame transferred onto them.

But dancing to ‘A Century of Solitude’ only got Uncle Raymond so far. When his popularity dipped, he expanded his repertoire, first creating new dances before moving on to skits.

He would have faded away into quiet obscurity if not for his latest (and highly contentious) innovation: Uncle Raymond’s Dating Show.

Uncle Raymond’s Dubious Dating Show

I wasn’t the only one who felt something amiss about his dating show. It seemed like Uncle Raymond was almost exploiting his ‘interns’ for views. In September 2023, The Straits Times reported that Uncle Raymond and his dating show had come under fire for exploiting people with intellectual disabilities.

Of course, the unspoken and harmful assumption here comes in two folds. One: his ardent followers—the ones who are happily taking part in Uncle Raymond’s antics—are people with special needs. Two: people with disabilities lack the mental capacity to process the consequences of following whatever Uncle Raymond asks them to do.

Two social work professionals, Ms Lee and Ms Lim, were concerned that the matchmaking series took advantage of people with disabilities. TikTok users flooded the comments section of dating show videos to make fun of its contestants.

When a dating show video is posted, TikTok users rush to the comments section to read mean remarks about its contestants for mindless entertainment. The online platform sees this as engagement and promotes the videos, inevitably begetting more trolls.

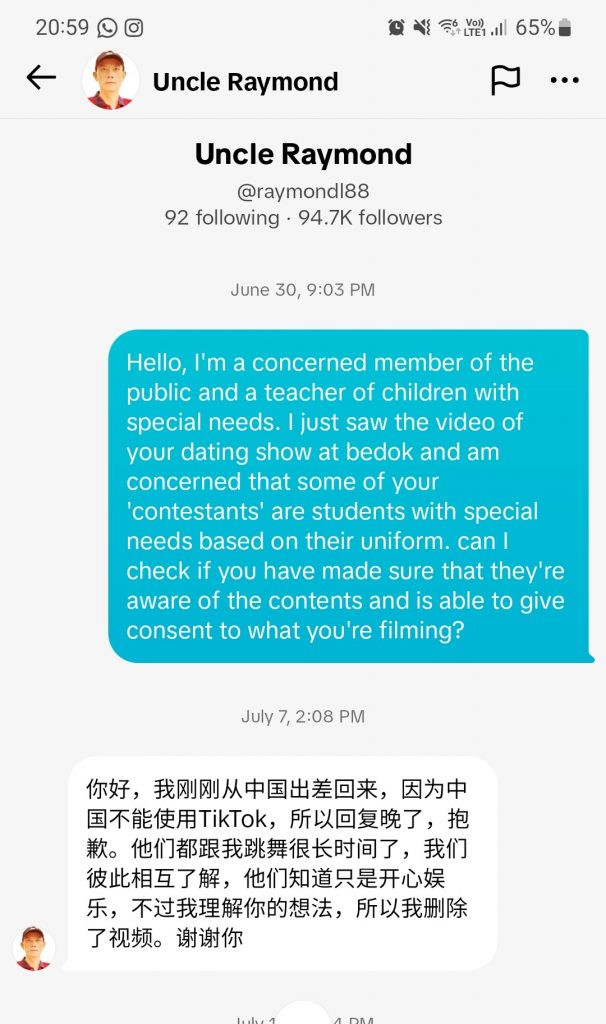

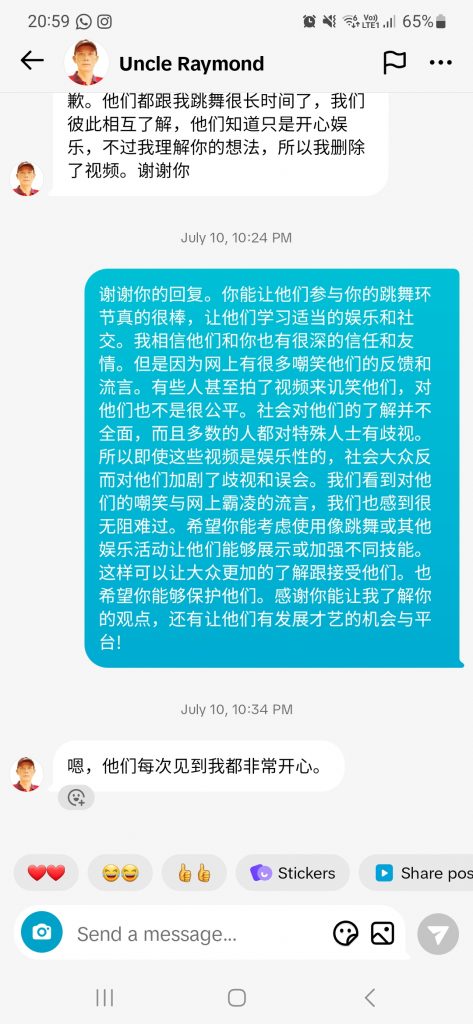

When RICE spoke to the same two social work professionals, Ms Lee and Ms Lim, they revealed that they messaged Uncle Raymond on TikTok and raised their concerns that some of Uncle Raymond’s dating show contestants were, based on their uniforms, students with special needs.

They also asked if Uncle Raymond would consider other video formats that could raise awareness and understanding of people with disabilities rather than expose them to the inescapable online vitriol.

Uncle Raymond responded by removing the dating video showcasing students in their uniforms. But, as to whether he would consider other types of videos, he responded to the them in Chinese: “[The participants] are happy every time they see me.”

The Brave, the Bold, and the Bald

In his response to The Straits Times, Uncle Raymond addresses concerns about online bullying, saying that there will always be “such people in society”.

He regards online trolls as a fact of life—they will always be present on the internet, so he can’t be blamed for the bullying.

But it takes two hands to clap. His videos fuel vitriol and the same vitriol fuels his content. Some responsibility still falls on Uncle Raymond’s shoulders.

Watching an Uncle Raymond video can be a disconcerting experience. For whatever reasons, you might enjoy watching his clips, but that very view also promotes the same video to other Singaporeans—ones who have more nefarious inclinations.

No matter how well-intentioned, there is some complicity involved. And that online bullying, as mentioned in The Straits Times, only reinforces the stigma surrounding persons with disabilities.

In some ways, we are all part of the grandeur of Uncle Raymond’s act. He posts a video. TikTok users flood it with comments, some of them mean or unnecessarily cruel. The video is promoted. More comments enter the fray. The cycle repeats.

Uncle Raymond’s entourage has more to say about the issue. And the best way to reach them is to find Uncle Raymond himself.

On The Hunt For Uncle Raymond

Uncle Raymond informed the public that he would appear at Ang Mo Kio MRT Station at 4 PM. Admittedly, my colleagues and I are 15 minutes late to the show.

He was nowhere to be found. The only trace of his presence was a livestream he had started a few minutes ago. On the livestream, Guo Lai—Uncle Raymond’s most infamous ‘intern’—looks on nonchalantly as Uncle Raymond answers the gamut of questions from TikTok users.

Passersby with trays of food in their hands shuffle behind him. Their gazes immediately turn away from the camera’s view when they walk past, careful not to be caught on the livestream.

It was at a food court in Ang Mo Kio Hub where we eventually found Uncle Raymond. He sits dead centre in the food court with a phone stand precariously propped up in front of him. Say what you want about him, but he knows how to be seen.

This time, Uncle Raymond sports a noticeably faded version of his iconic red polo shirt and a backwards baseball cap. He is close to ambling away before we approach him for a chat.

He obliges after some persuasion. Our impromptu interview request is making a dent in his plans; he’s supposed to head off to a friend’s house to help sell durians on a live stream.

We ask how he feels about the criticism levelled at his dating show. Responding in Chinese, he gives a similar response to the one he gave to The Straits Times.

“I do not earn money from making online content. People who are interested in filming videos with me show up voluntarily.”

38-year-old Wong Sing Sheng Tommy, better known as Guo Lai, concurs. The man behind the ‘white white drink’ shenanigans started meeting Uncle Raymond at different locations late last year. He rejects the allegations of exploitation.

“Uncle Raymond did not make use of us. We all like to dance to him. Dancing is exercise. It has made me healthier,” he remarks.

“Uncle Raymond also gives me a lot of advice. I’m actually quite a hot-tempered guy. With Uncle Raymond, I learned a lot from him. He told me to calm down and how to control my temper.”

21-year-old Adam, a fellow ‘intern’ since September last year, also expresses support for Uncle Raymond despite recent criticism.

“After I joined Uncle Raymond, I made new friends. We share an interest in creating online content,” he says.

“It’s nice to have other people to talk about content ideas. I asked my friends, and we came to a consensus,” Adam elaborates after being asked how he feels about the dating show. He clarifies that it’s all for fun—they aren’t really out to look for love.

“We agreed that we’re going there to support Uncle Raymond. I personally would never get to experience a dating show, but I can with Uncle Raymond.”

Like some of his other co-stars, they are acutely aware of what’s going to happen when they associate themselves with Raymond.

“We don’t really care about the hate comments. Or any comments in general.”

The Principle of Self-Determination

Adam also alludes to a principle in social work that makes it especially difficult to pinpoint what exactly Uncle Raymond is doing wrong: The Principle of Self-Determination.

Generally speaking, people should be allowed to make their own decisions and determine their own lives. This principle applies when social workers support and help people with disabilities or special needs.

Sometimes, the principle of self-determination conflicts with the duty of care—an obligation to intervene and prevent someone from making their own choices.

According to the two social workers we spoke to, people with disabilities should be allowed to make their own decisions, even if those decisions lead to detrimental consequences. That’s assuming that everyone in the entourage is a person with a disability. And that’s not true.

People with disabilities should be allowed to make their own decisions, even if those decisions lead to detrimental consequences.

It’s like letting someone have a cheeseburger for lunch. It might not be the healthiest option, but they should be allowed to make that choice. And Uncle Raymond’s supporters are doing just that: Leading their own lives and making their own decisions. It allows for equal opportunities for them to succeed, and conversely, make mistakes and learn from them.

They’ve accepted that horrible online comments come with the territory of pursuing stardom. Unless someone can prove beyond doubt that his ‘interns’ are under emotional and psychological abuse, Uncle Raymond will continue to make his videos.

Abuse seems unlikely. No one’s coerced into doing anything they don’t want to. His supporters only have positive things to say about him. Guo Lai describes Uncle Raymond as a mentor who doled out advice which improved his life; Adam treats Uncle Raymond as a teacher and a friend.

Perhaps that sense of dedication comes from Uncle Raymond’s acceptance of who they are, something that they might not experience from other public figures with influence. And there’s nothing wrong with finding that sense of community.

Coming to Terms With Uncle Raymond

But that doesn’t justify spewing hate in the comments section, simply because the people who chose to put themselves out there have accepted this fact. And it doesn’t mean that a person with special needs or disabilities doesn’t have the mental capacity to make choices on their own.

A more fitting question is whether we should encourage this warped feedback loop—we give them the time of day for the wrong reasons and encourage them to do more videos that invite even more horrible comments.

If anything, perhaps that sense of discomfort when watching Uncle Raymond videos arises because we’re as much culpable for encouraging more controversial videos, like how Guo Lai’s Love Triangle Saga unfolded.

Uncle Raymond will continue to post his videos; at least, that’s what he tells RICE. And his followers will keep doing what they do. But there’s cause to reflect on the intersection between viral fame/infamy and how Singaporeans treat people with intellectual disabilities.

It’s in that intersection that we find this uncanny discomfort.