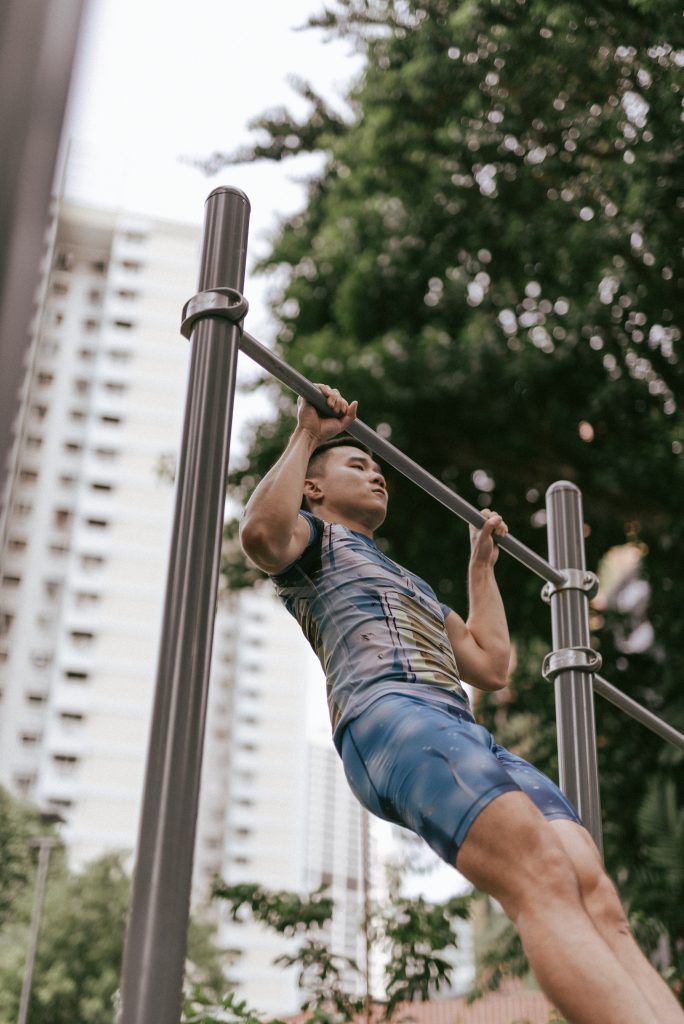

All photos by Jamie Sim for RICE Media.

There are many ways to injure yourself from throwing a punch. As many as there are months in a year—maybe more, if we’re keeping count.

Chances are, you wouldn’t think about potential injuries before throwing a punch at something (or someone). As long as your fist makes an impact, that’s all that matters, right?

Maybe, if the other party deserves it. Not so much, however, if you’re a professional fighter. It’s a physical sport, yes, but there’s more to it than just simply throwing down.

It’s the thought behind each punch that turns it into a sport. Will it land you points? Or will it be a strike that ends your career—or your life? The latter is what all professional fighters avoid. But it takes a lot more than guts and smarts to even out the (often dangerous) stakes.

Eye of the Tiger

Professional fighting is about the push and pull, a primal and animalistic dance with two individuals clashing again and again until a winner is decided. We see it in wrestling programs, MMA events, and even in Pokémon.

Standing at 178cm, 34-year-old professional wrestler The Eurasian Dragon appears more like an unshakeable monolith than the down-to-earth friendly bear that is Kenneth Thexeira, his real name and off-stage persona. Given his build, I assume that when he gets choke slammed, it would feel only as painful as dropping a phone on your face.

He laughs. “No, the pain is real,” he emphasises.

Professional wrestling features as much flashy theatrics as there is rugged combat. Think of the biggest wrestling shows in the world with grand moves (known as “finishers” in wrestling parlance) like the Tombstone Piledriver, the Buckshot Lariat, the Molly-Go-Round and every other move with an absurd and absurdly cool name.

Results are predetermined, scripts are written with whole storylines meant for gripping entertainment. But that doesn’t make the fights themselves fake; it all has real stakes. To convince the audience, there must be a certain degree of violence. The punches do connect. You can’t just will yourself to get a nosebleed from an air slap.

The ring itself is no bouncy castle either. Even if blows are restrained, getting slammed into the canvas mat hurts. The audience can hear it when wrestlers’ bodies collide with concrete, metal chairs, and ladders. There’s no faking that.

“I’ve seen people tearing their ACLs (the ligament that connects your shin to your thigh). There are those who don’t break their fall right, and their shoulder hyper-extends and separates,” he shares, shrugging. “Injuries are just part and parcel of being a professional fighter.”

At the very least, he adds, he hasn’t experienced anything a little spit won’t fix.

Thrill of the Fight

Professional fighters rely on their bodies for a living. Not to call them pessimists, but they go by a sacred, unspoken rule that guides their extreme caution: “Whatever can go wrong will go wrong.”

That’s probably why they’re all about eating well, sleeping well, training religiously and having really comprehensive medical coverage (yes to accident plans, hospitalisation plans, everything).

At his peak, Mixed Martial Arts(MMA) fighter Benedict Ang trained twice daily, seven days a week.

The 26-year-old, who goes by the nickname ‘The Saiyan’, likens the sport to a legalised street fight.

“When you’re in the ring, you’re counting on the referee to protect you from life-threatening injuries. They’re there to enforce the rules. Everything else [between you and your opponent] is fair game.”

Unlike professional wrestling, where wrestlers learn to minimise the damage inflicted and received, MMA is about actually hurting your opponent. How can it hurt less? You’ll just have to be a better fighter. Not just in terms of offence and defence, but being able to read the flow of the match well enough to avoid hits altogether.

Like Kenneth, Benedict considers himself lucky to have gotten away with only minor injuries—a bevvy of sprained finger ligaments or a split on his brow bone.

The worst injury? A torn meniscus (knee cartilage) suffered from a training session gone wrong. It required platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections, a process that increases the amount of cell-regenerative plasma in a blood sample that’s reinjected into the wound to accelerate healing.

To get treated, he had to seek out his usual orthopaedic specialist at Mount Elizabeth hospital. Nothing his insurance policies couldn’t cover, fortunately.

“Accidents happen all the time,” he assures. “It’s not something you can predict nor prevent.”

At this point in his decade-long career, he’s nonchalant about it. Perhaps it really is just a minor inconvenience. At least, compared to his peer who once threw a kick in a match and broke his shin in the process.

That’s still leaving out the normal kind of accidents anyone might encounter on a bad day.

While on holiday in Bali last year, Benedict got into a bike accident that left him with seven screws and three plates in his foot. He’s gotten them removed since, but gone was the optimum level of performance he once had. All he can do during rehabilitation now are bodyweight workouts and strength training.

Beyond the Limit

If Amanda Chan had to guess, no fighter enters the ring a hundred percent healthy.

Despite being just 33, the professional boxer has eye floaters, a condition that typically afflicts those over 50. On top of her pre-existing myopia, parts of her vision get obscured by the shadows of scattered clumps of collagen fibres that drift about in her eye.

The other (common) cause of floaters? Trauma to the eyes and head. That’s boxing in a nutshell.

She also nursed an injured hand during a recent match, where the slightest touch would result in a sharp, nearly blinding pain. Still, she won.

I met Amanda during her preparations for the WBC Asia Champion title fight, the most prestigious boxing competition in Asia. Our conversation was punctuated by sniffles—she had a whole roll of tissue tucked under her arm, meant for wiping her nose. The recent bout of flu got to her too.

It’s easy for outsiders to call them foolhardy or reckless. But for professional fighters, there’s no such thing as holding back, let alone giving second chances. Those few precious minutes in the ring are all they have.

There’s no time to think about their injuries or worry about the pain. The only thing on their mind is to give their best performance—anything less than that isn’t good enough.

“The moment is so, so short-lived,” Amanda says. “I’ll just deal with the consequences later.”

Perhaps for Amanda, the need to push herself to such an extreme partially stems from the short career lifespans professional fighters have. Most of them retire as they enter their 40s. Amanda, who only started boxing professionally at 26, knows the clock is ticking. To go as far as possible, sacrifices are necessary.

To borrow the words of Troy Bolton, it’s now or never. (Spoiler alert: Amanda clinched her title as WBC Asia Champion at the time of publication.)

Last Known Survivor

An unfortunate part of a professional fighter’s reality—at least in Singapore—is also having to work a day job to supplement their income. Kenneth works at an interior design company; Amanda is a boxing coach; and Benedict, unsurprisingly, is a fitness trainer who conducts his lessons online.

They earn appearance fees whenever there’s a fight. These only happen maybe between four to eight times in a good year.

In other words, when they need time to recover, they lose the time spent earning money. This obviously excludes the emotional stress and concern from family members and friends.

Taking care of their bodies can be considered their real “main” job. Doctor visits are frequent, as are trips to the TCM (traditional Chinese medicine) specialist and chiropractor.

Kenneth relies on private clinics. The wait required at public ones just isn’t worth the prolonged agony. Similarly, Amanda brings up one incident where she headed straight for Mount Elizabeth Novena Hospital when she caught a horrendous case of food poisoning.

“Our public hospitals are great! But when I’m in such a vulnerable state, I just want to get help faster. My insurance covers it, so why not?”

As expected, all three fighters have comprehensive coverage—the usual concoction of accident plans, hospitalisation plans, life insurance, you name it. Beyond just the regular Medisave and Medishield coverage, Amanda and Benedict also have Integrated Shield Plans (IP), which provide additional medical coverage to foot the private hospital bills.

Once, Amanda broke her orbital bone, a part of the eye socket. She saw the billed amount—it was hefty.

Fortunately, she had company insurance at her previous job that paid for her entire treatment. When she left that job, the first thing she did was secure her own coverage.

Benedict is familiar with hefty medical bills too. His biking accident would’ve been costly had it not been for his IP.

The initial emergency treatment in Bali was covered by travel insurance, but it was his IP that paid for a follow-up surgery in Mount Elizabeth.

He shows me the bill: it’s a handsome five-figure sum. Using a hospital bill estimator, the cost and final estimated cash outlay were all laid out clearly to see. The visibility made seeking treatment so much easier.

“When I’m down for the count, the last thing I want to think about is the incoming hospital bill,” he says. “I make sure I have all my bases covered.” Much like fights in the ring itself, I suppose.

It’s only then will professional fighters be able to throw themselves into the job. Only then will they be able to give the audience what they want.

Watching Us All

Kenneth tells me he had just gotten married a couple of days prior. The photos show a cosy private wedding, with Kenneth surrounded by the people he cares about the most. All wholesome smiles, all around.

Throughout our conversation, it’s clear he loves his job. He also loves his wife and family. It’s the last thing he wants to jeopardise.

Still, professional fighting will remain a risky job. That much won’t ever change. In turn, he does whatever it takes to safeguard his life.

More training? Better insurance coverage? Mindful diets? He’ll do it all.

“It makes sense to be safe, you know? At the end of the day, I just want to be able to walk home to my family and wake up to greet them the next morning. That’s all.”