They pop up inconspicuously on your daily commute. Subconsciously, you know where they’ll be. Their bare setups usually consist of tables, chairs, umbrellas, and crisp newspapers.

They are the newspaper vendors that we’ve grown to forget.

The last time I bought anything at these newspaper stands was 18 years ago for a school project. So when I started this photo essay, I was clueless about their operating hours.

I arrived at two stalls in Toa Payoh at 10:30 AM to find foldable tables covered by tarps. “Before sunrise, same as the market,” their neighbours tell me about their operating hours.

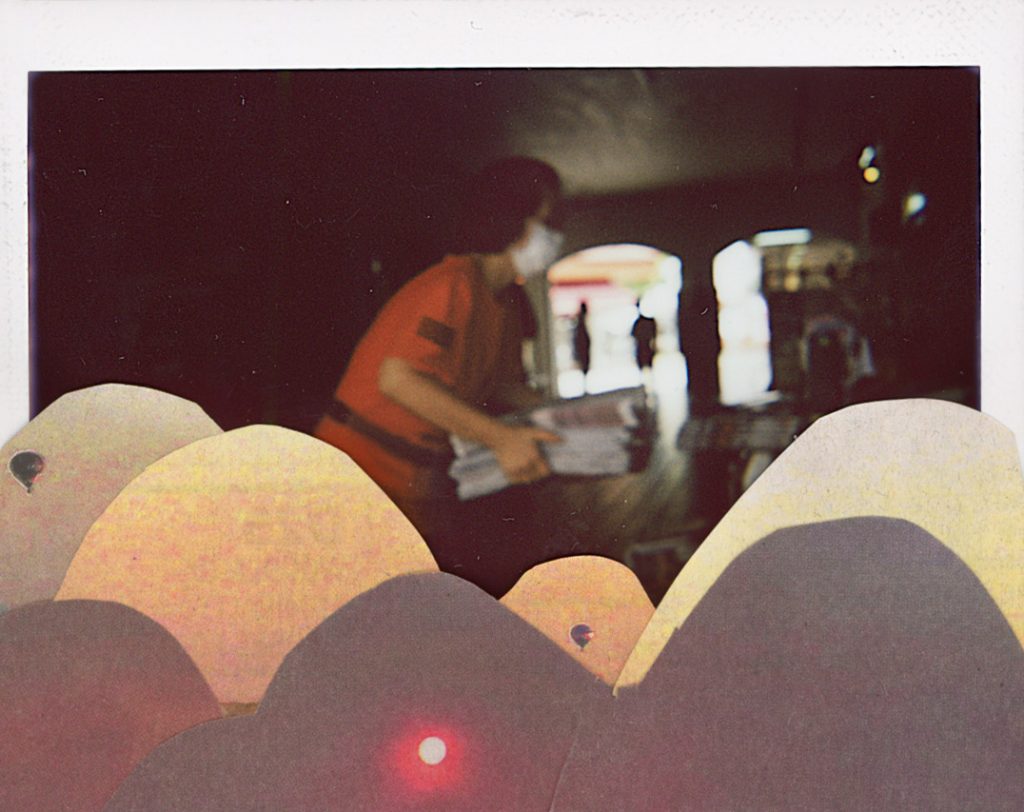

The second time’s a charm. I spotted an open stall from afar, which made waking up at 5 AM worth it.

Situated at 22 Lorong 7 Toa Payoh, Uncle Low’s booth can be found next to a deity altar at Kim Keat Palm Market and Food Centre. He tells me he has been there for six years, but the booth has been there far longer. He’s the fourth person to take over the stall.

“One of them went to an old folks home, and two have passed away,” he offers nonchalantly.

The responsibility of caring for the market’s stray cat was also passed down to him.

“It comes to my stall to eat when I open at 3:30 AM and comes back again in the afternoon. It has been around for over 10 years,” Uncle Loh tells me.

Uncle Loh repeatedly mentions that he wants to stop working. He doesn’t want to wake up so early anymore just to earn 10 cents per newspaper copy sold.

“What happens to the cat after you retire, then?” I ask.

“If I stop working, the person who takes over me will take care of it,” he replies. I guess the responsibility will fall to his neighbours if his booth does end up closing.

To Survive is to Look Out for Each Other

Among all the street hawkers (roasted chestnut hawkers or clobbers, for example), I am most drawn to the newspaper vendors. Mostly because the main product they’re selling—newspapers—is falling out of fashion. Along with the declining demand for the product, its independent sellers are the next to fade away.

Much like the end of Golden Mile Complex and the impending closure of Singapore Turf Club, we can only watch as these cultural landmarks and trade disappear from Singapore’s landscape. The only way I know how to preserve the memory of their existence is to photograph them.

My luck improves as I continue my pursuit of uncovering this disappearing trade. I found out that most of these vendors aren’t independent sellers. Some work for newspaper distributors, and they get either get paid per copy sold or paid hourly to operate the booths.

Uncle Ah Chai and Auntie Ah Bee, however, are independent vendors. Their stall in Tampines came highly recommended by my former colleague, Eve. “I used to buy magazines like Seventeen and Teenage from them,” she reminisces.

Ah, the days of reading ‘Dear Kelly’ columns for my non-existent BGR problems. Gone are the days when teenagers had to wait a week to catch up with their idols’ latest happenings (shoutout to the Teenage magazine issue that came with an A3 poster of Avril Lavigne) or solicit advice from an anonymous columnist.

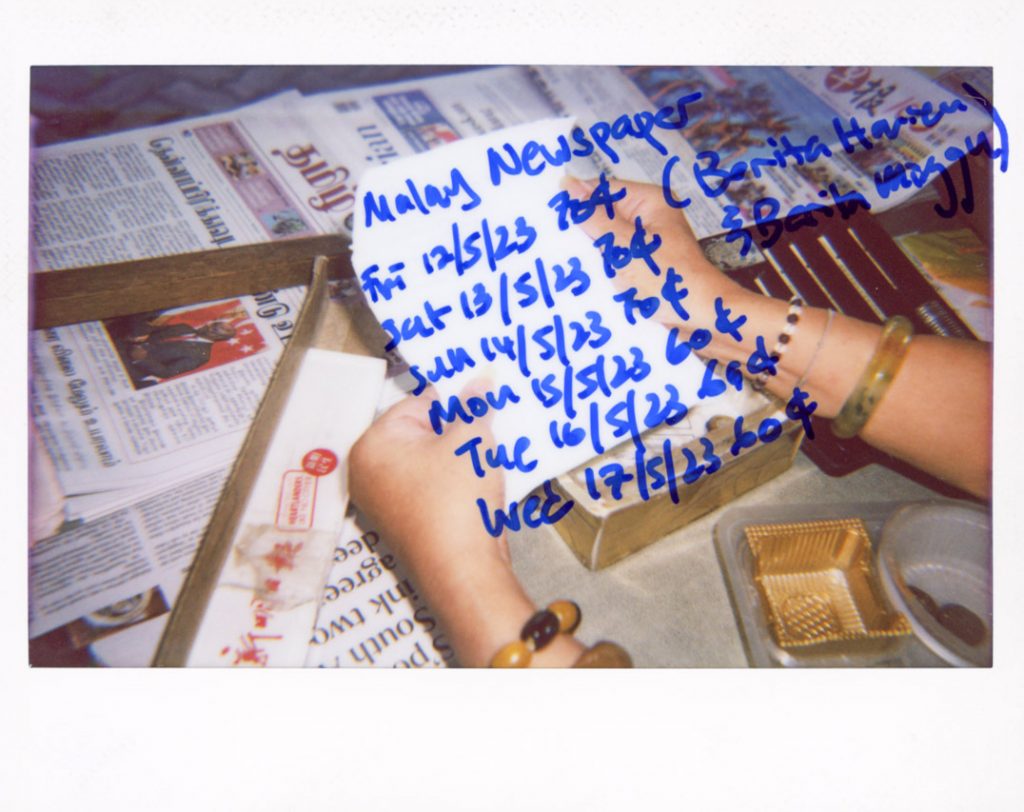

They break down an overview of their sales. 25 percent of their sales come from magazines, horse-racing booklets and lottery tickets. The rest comes from newspaper sales.

Uncle Ah Chai and Auntie Ah Bee’s customer base has shrunk to elderly residents living around the area. Being a physical node in the community also means they would notice “someone whom they have not seen for a while,” says Uncle Ah Chai.

Every morning without fail, Uncle Ah Chai would go around the neighbourhood to personally distribute the newspapers on customers’ doorsteps before manning the stall. He tells me he only has two rest days: the first day of Chinese New Year and Christmas Day.

Besides keeping a mental count on neighbours, a segment of the stand is set aside to hang umbrellas. Auntie Ah Bee shares that the brollies are donated by the residents in this area.

“When it rains, anyone is free to borrow.”

She pulls out bundles of recyclable bags gifted by neighbours, which she uses in place of the usual disposable ones. This organic interdependence between a dying trade and its regular supporters seems promising for the longevity of the stall.

Yet, Auntie Ah Bee gives this sunset industry “maybe another five to 10 years”. She takes a beat before correcting herself.

“No, I think five years would be a miracle.”

“Will you miss your customers if you stop operating?” I ask.

“They will all go online to read the news; there’s no point in missing them,” she responds, resigned to her fate.

Maybe she’s right. Dear Kelly would advise that there is no need to pine over an unrequited relationship.

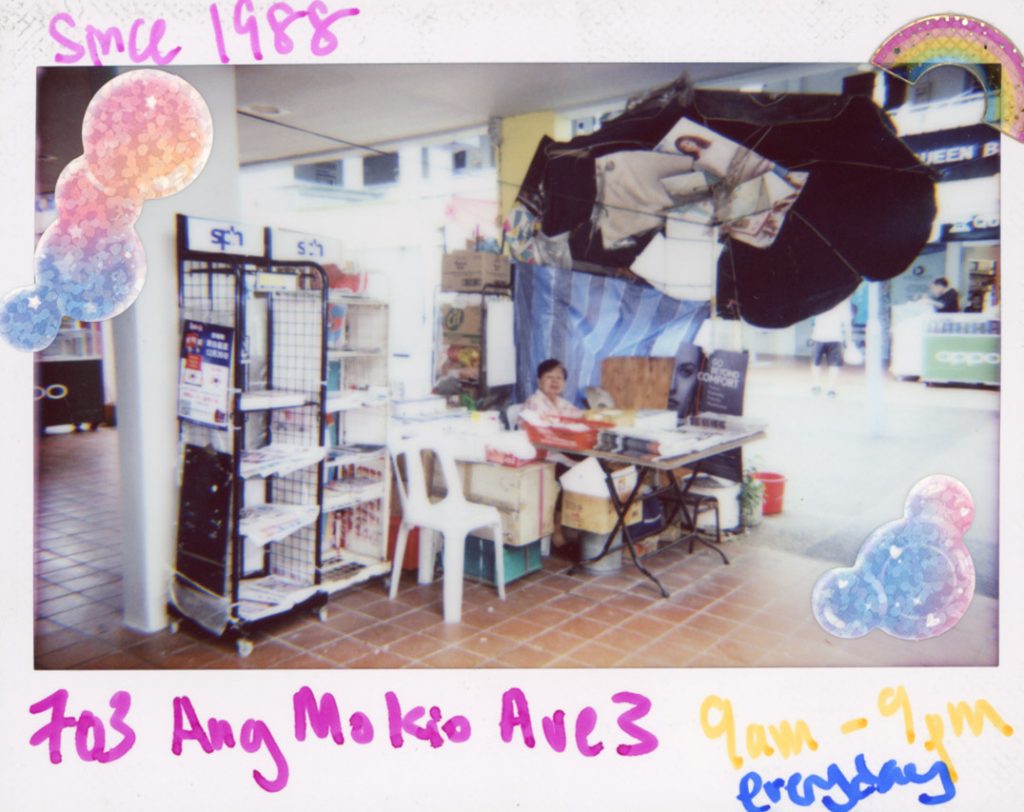

Over in Ang Mo Kio, Auntie Tam has a different take on her probable heartbreak.

Even at 87 years old, she’s brimming with life and laughter. I’m sure my family will have lots of laughs too if they hear me struggle to converse with her in Teochew.

“I will miss [the customers]; they are very nice,” she says to me in Teochew, the only language she knows how to speak. When she was a child, her parents disallowed her from speaking in any language other than Teochew.

“Everyone here shio shio (dotes on) me,” she beams. They would buy her food like kopi, kueh, prata, kway teow and chicken rice.

This was evident when a helpful neighbourhood resident stood on the side throughout the interview as my impromptu translator. Other regulars interrupted our conversation to check if she was becoming a celebrity.

After all, she has been selling newspapers in the area since 1988. The little community that has since formed around her became her solace since her husband and son passed on in recent years.

“I am all alone. If I had stayed home, I would just be mourning,” she says.

She tells me about a recurring dream. It involves her wanting to enter a door, but someone keeps denying her entry. The person will usually tell her that she won’t be able to return once she goes through that door. She would insist to the person that she wants to look for her son.

“The person would say no. Then I’ll wake up.”

The Friendship Beat

Perhaps when we start looking out for others, others look out for us too. A year ago, Auntie Goh had offered Uncle Albert, a guitar teacher, a space to put his guitar and a place to sit at her newspaper stand in Bukit Panjang when his leg was hurting.

Grateful for the kindness, Uncle Albert has been assisting in closing her stall every day since then. He even bought a portable radio for her to listen to.

“Both of our legs took turns to get injured,” laughs Auntie Goh. When she was hospitalised a few months ago, Uncle Albert helped to look after the stall.

Auntie Goh will only retire when she can’t walk anymore. “I will miss interacting with everyone and being happy, compared to being bored at home,” she offers cheerfully.

Her optimism must have translated into her sales—she’s the only vendor who tells me that business is good. She had almost finished selling her newspapers that morning.

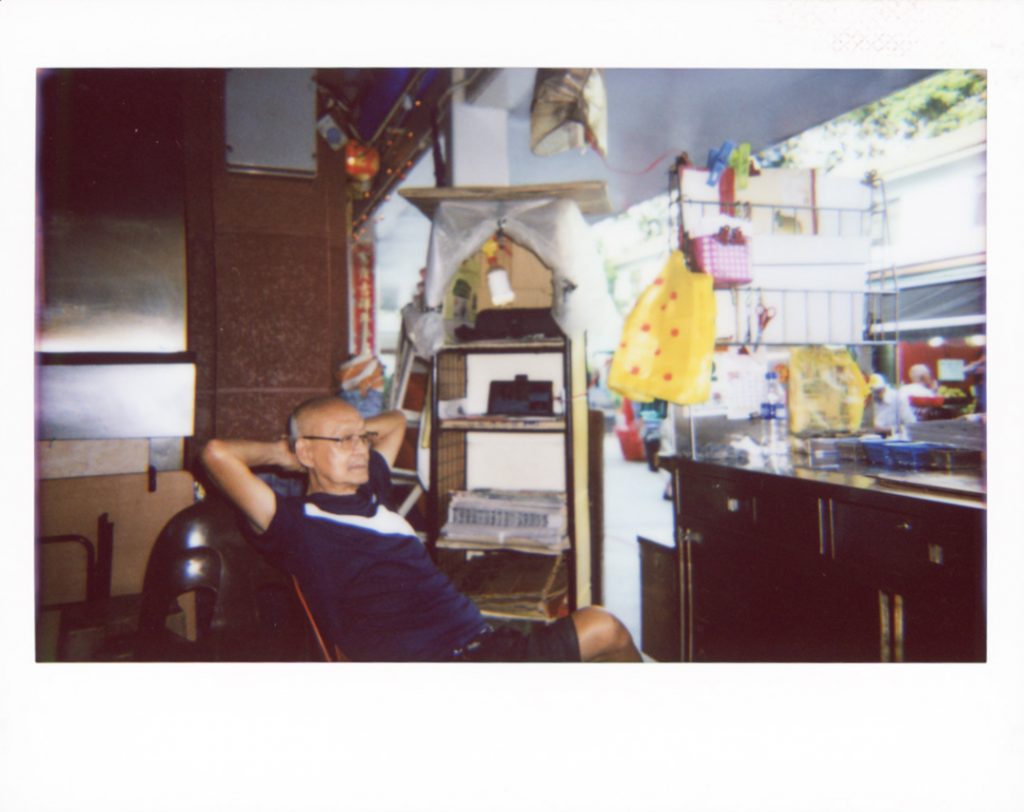

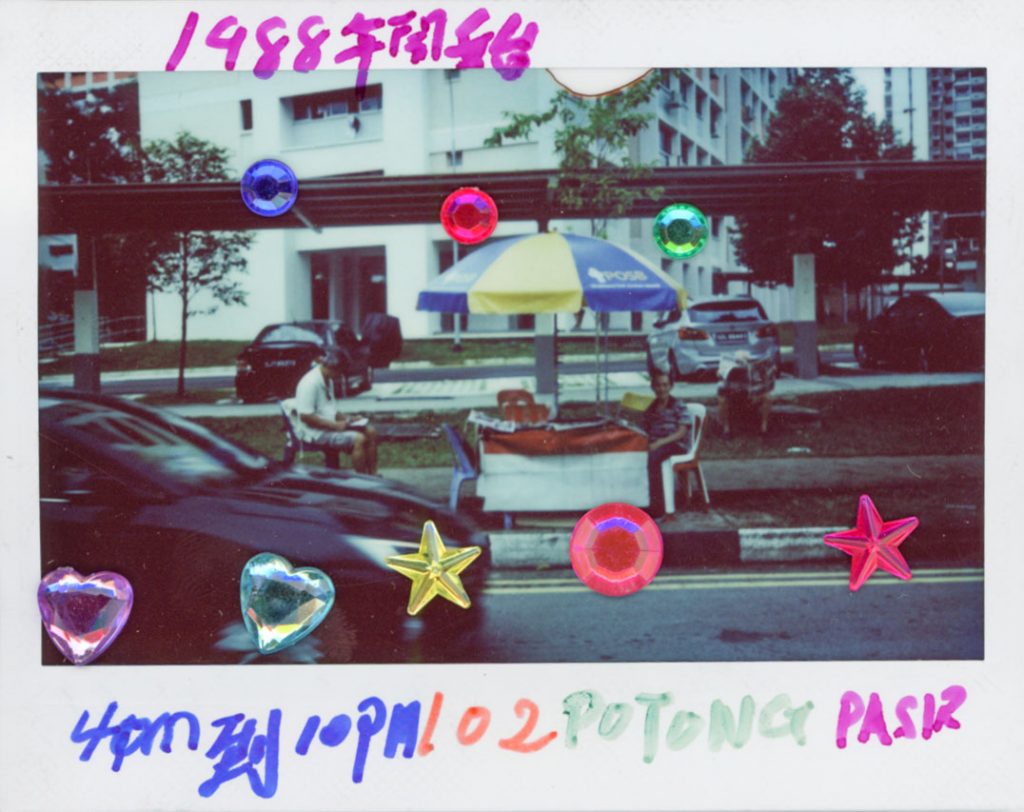

Uncle Yang, on the other hand, experienced a drop in business at his Potong Pasir stall since Lianhe Wanbao merged with Shin Min Daily News in 2021.

Even with one less option, Uncle Yang still has regulars who come to hang out at his stall every day. The casual congregation stretches from the roadside to a little slope behind his stall.

I count five people sitting on chairs (some had left home for dinner) he puts out for them. He considers it a quiet day.

It certainly didn’t sound like a quiet day. I hear regulars discussing the news and playing old Hokkien tunes on their phones.

Once in a while, motorists would stop by the side of the road, and Uncle Yang would pass them a newspaper. They’re his regulars—he already knows which newspapers they want.

One of his regulars coincidentally shares the same name: Ah Seng. He has been visiting Uncle Yang without fail every day for 38 years. They would chit-chat and buy each other kopi—gestures which Uncle Ah Seng emphasises: “This is call friend. Peng you.”

The Sun Sets

When I started, most people could not offer me the exact location or the operating hours of these makeshift stands. It was either “I’ve seen it on my way home” or “It’s next to the coffee shop near my house”.

With no names, no signboards, and no clear operating hours, none of them can be found on Google Maps. They’re primed for us to forget about their existence.

The common thread throughout my romp across the island is the kampung spirit that encapsulates these stands—something I’ve never seen first-hand.

For older Singaporeans, I think it gets harder for them to form new bonds. At their age, it’s tougher for them to latch on to common interests with peers or find new ways to pass their time.

For them, these newspaper stands give them a sense of meaning and familiarity—a consistency incorporated into their daily routine. And when these spaces fade away with the sunset, so will the things that anchor them to the community.

As these newspaper vendors slowly disappear, there won’t be much fanfare. But subconsciously, we’ll notice something is missing.