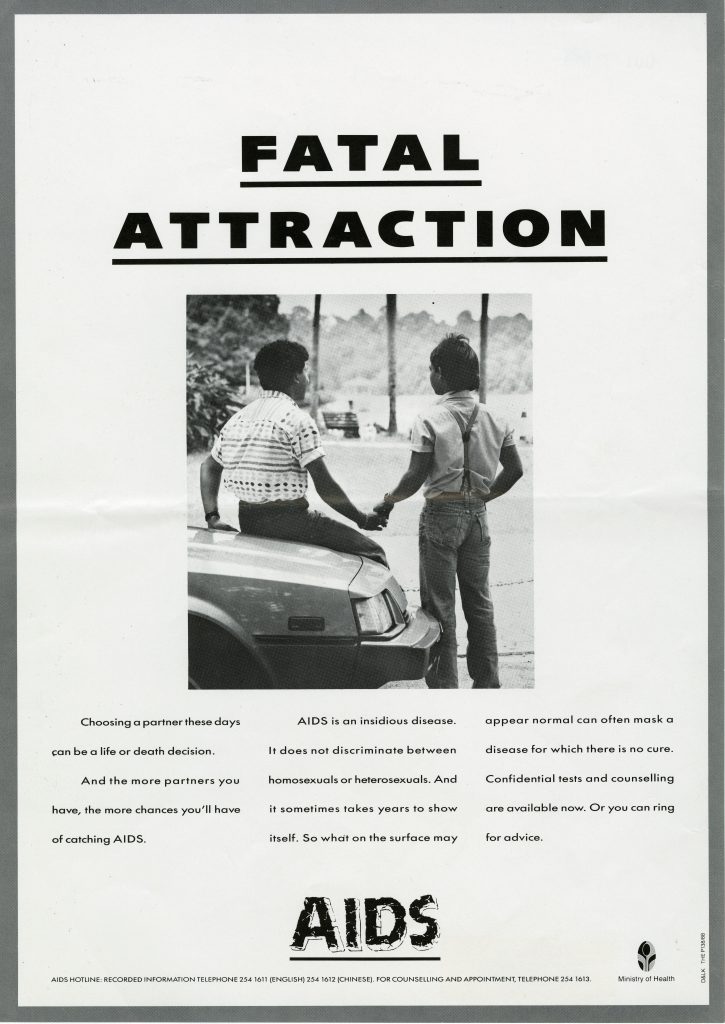

Top image: Cropped from a 1988 Ministry of Health poster.

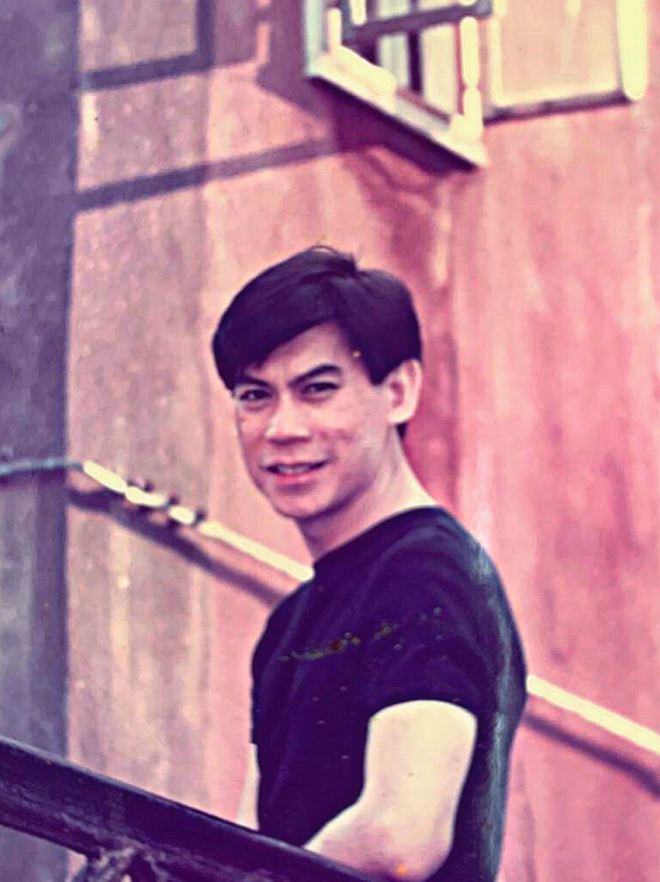

It was the mid-1980s when Paul Toh came of age as a gay man, decades before smartphones and dating apps made sex a lot more accessible right at your fingertips. Toh has been diagnosed with HIV since 1989.

Now semi-retired with his own business distributing antiretroviral therapy medication and HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), the 59-year-old said that in those days, cruising in public parks, toilets, and back alleys of dirty shophouses along pre-cleanup Singapore River for sex was par for the course.

ADVERTISEMENT

“It was interesting and challenging since it wasn’t only about hooking up with other men; there was also an art to the chase and pursuit,” said Toh.

Unsurprisingly, cruising in public made gay men easy targets for police officers. “They started going to these cruising grounds undercover, with the explicit intention of entrapping and arresting gay men,” Toh added.

Police raids in nightlife establishments with gay clientele also became common, with prominent gay discotheque Niche having its liquor license withdrawn by the police in 1989 and the Rascals incident of 30 May 1993, in which multiple patrons were arrested for not having their NRICs on them. This came to be remembered by veteran activists as Singapore’s Stonewall.

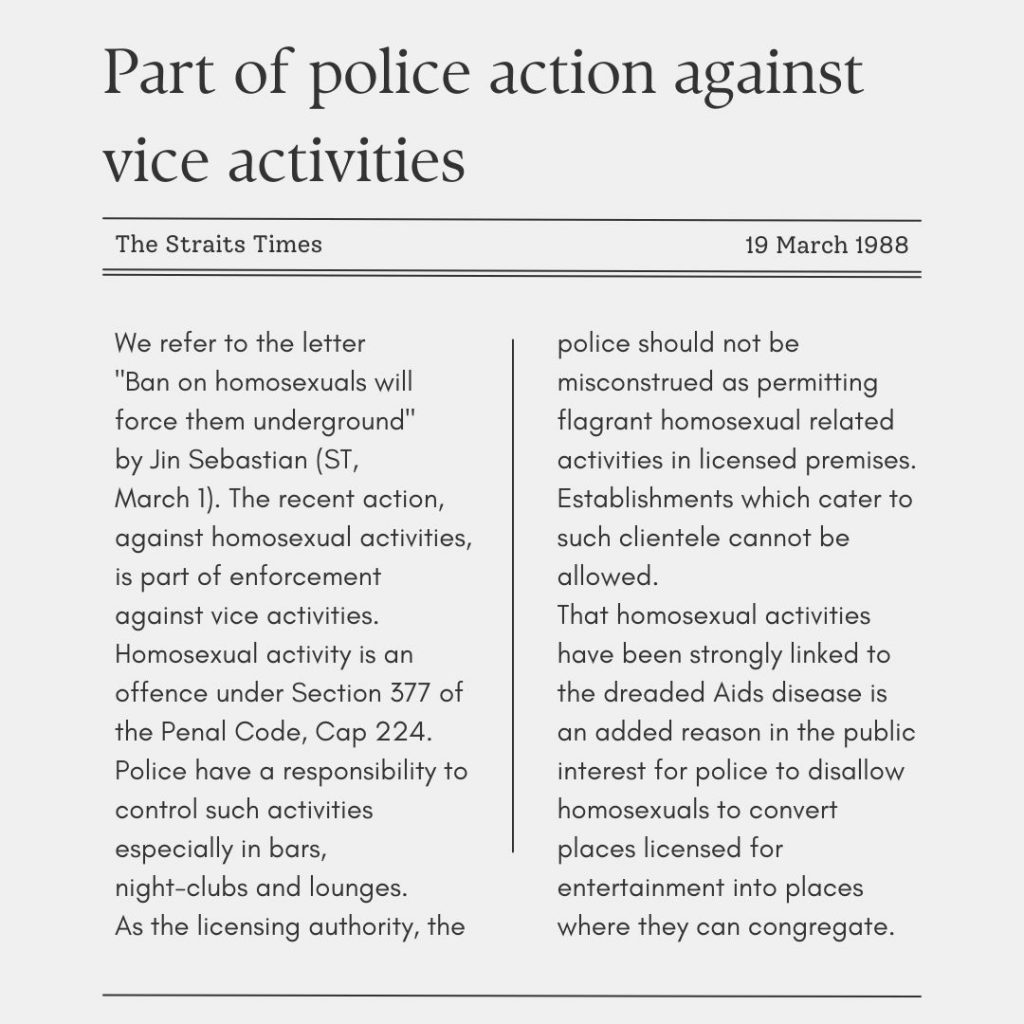

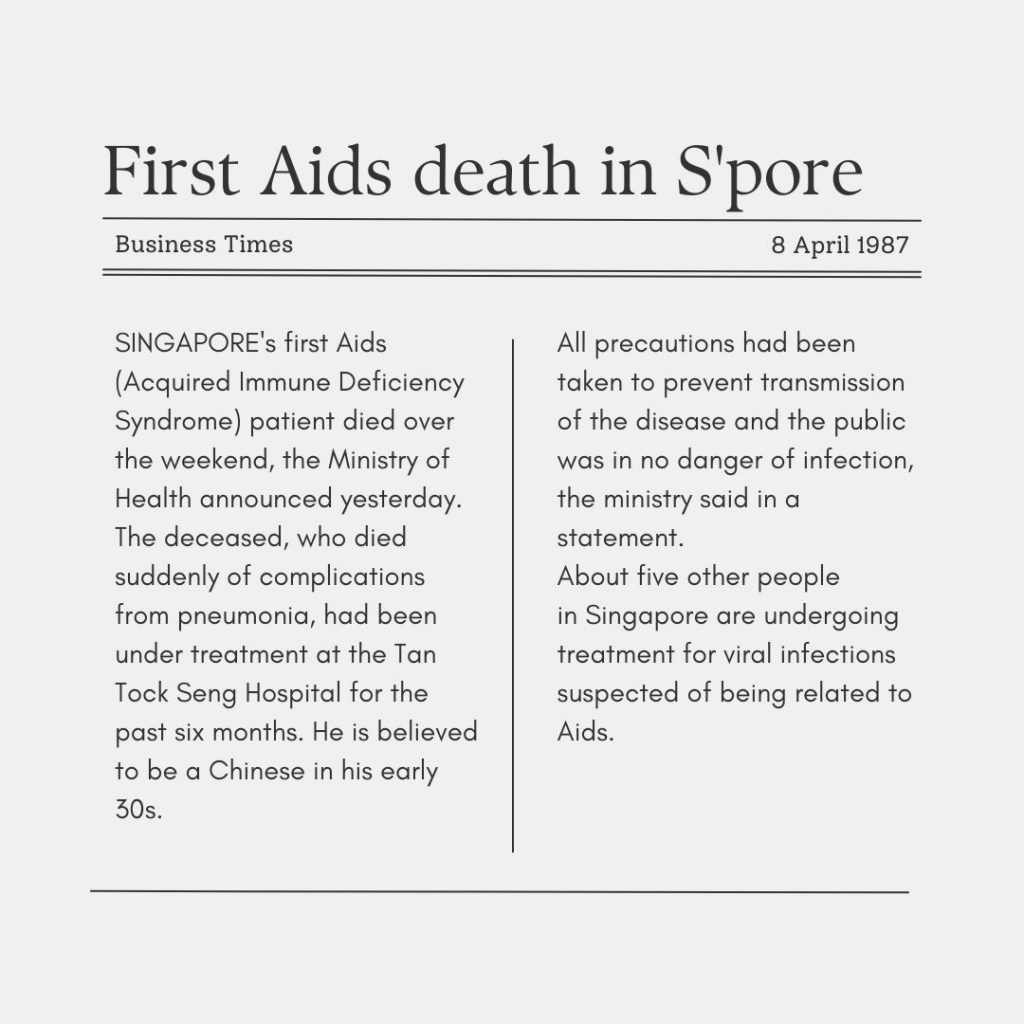

Fear about the spread of AIDS was part of the reason why police intensified their clamp down on queer spaces. In April 1987, Singapore experienced its first AIDS-related death. And one year later, the Director of Public Affairs of the Singapore Police Department said in a Straits Times article that “homosexual activities have been strongly linked to the dreaded AIDS disease,” making it an “added reason in the public interest for police to disallow homosexuals to convert places licensed for entertainment into places where they can congregate.”

Iris’ Work of Fighting Stigma

76-year-old health advisor Iris Verghese was among the first health workers to rise to the occasion when Singapore reported its first HIV/AIDS cases.

ADVERTISEMENT

“I knew just as little about HIV/AIDS as everyone else,” said the retired nurse, who first joined Middle Road Hospital, a now-defunct treatment centre for sexually transmitted diseases, in 1974. As part of her job, Verghese was tasked with contact tracing people who had sexually transmitted infections.

The job brought Verghese to brothels and nightclubs in Geylang’s red-light district, which meant she was no stranger to serving society’s Others with kindness.

“A lot of it has to do with my faith.”

“I thought about my role models like Jesus and Mother Teresa—they didn’t care what illness you had. If they could hang out with people with leprosy, then who am I to refuse to care for those with HIV/AIDS?”

Verghese’s work is well-documented, and everyone has given her the accolades she deserves—from President Halimah Yacob to the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Singapore to the Straits Times, which named her an everyday hero in 2019.

Plague, a 15-minute short film by Singaporean filmmaker Boo Junfeng, captures the emotional gravity of the care work performed by Verghese and health workers like herself.

The emotionally-stirring film is inspired by Verghese’s work with HIV/AIDS patients in the ’80s and offers a look into the life of Jamie, a patient who stopped coming to the clinic for treatment and counselling.

In the film’s climax, set in the patient’s HDB flat, Verghese tries to dissuade Jamie from inflicting internalised stigma. Jamie insists on using disposable plastic cups and utensils and cleaning every surface he touches for fear of passing the virus to his loved ones.

ADVERTISEMENT

Wanting to prove that HIV/AIDS is not transmissible through saliva, Verghese takes Jamie’s plastic cup and drinks from it. She then hands him a regular glass, beckoning for him to drink from it, only for him to swipe it away, breaking the glass and cutting himself in the process.

Thus comes the true test of Verghese’s dedication to her profession as she steels herself to the drastically heightened risk. Now that her patient is bleeding, she is dealing no longer just with saliva, but with blood carrying the virus.

“You happy now, Iris? You think you’re Mother Teresa?”.

In our interview, Verghese recalled many incidents like these. One that stuck with me was her counselling session with Singapore’s first HIV patient, a young gay professional, in 1985. “As I listened to him and gave him a hug, he broke down and cried,” she said. “He said he felt so good afterwards.”

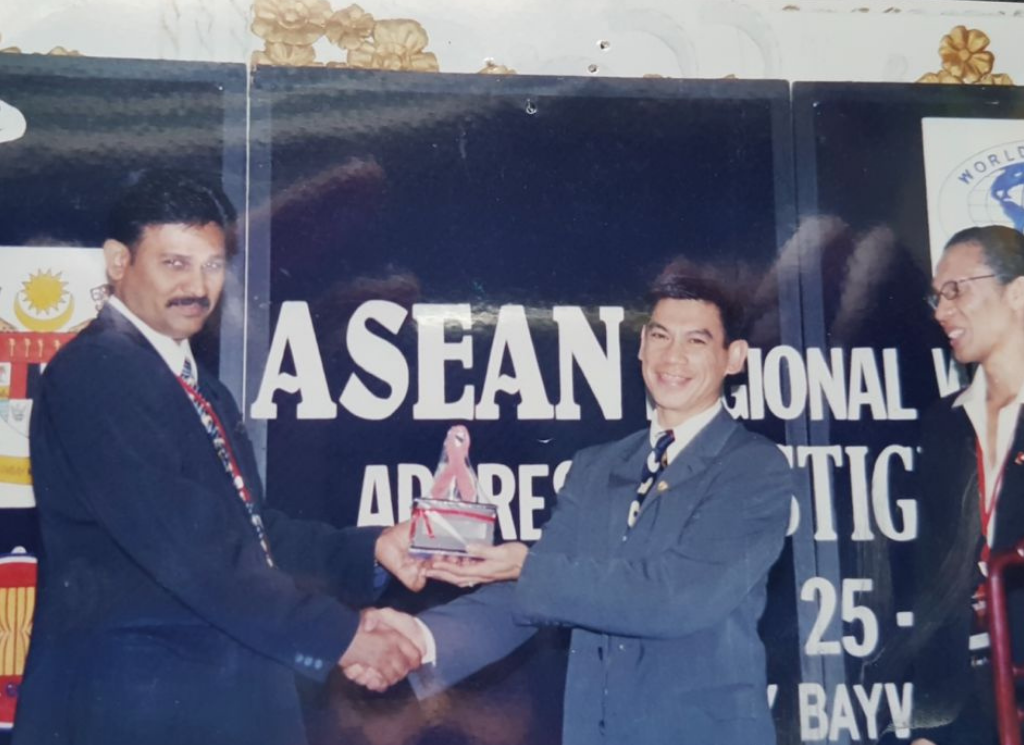

Iris advocating for HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment. Images courtesy of Irise Verghese.

Safe Sex Outreach in the 80s

“Things were very different in the ’80s and ’90s,” said Professor Roy Chan, Founding President of Action for AIDS Singapore (AfA). AfA is a non-government organisation founded in 1988 to fight HIV/AIDS infection in Singapore.

“There was no internet then. When we set up AfA, we had to rely on word of mouth, phone calls, faxes, pagers, and so on. Mobilisation was not as easy then, but we overcame the obstacles we faced. It was very much more hands-on in those days,” Chan recalled.

Chan set up AfA as a non-governmental organisation in 1988 to respond to the needs of people living with HIV/AIDS, regardless of their sexual orientation or gender identity, as well as to advocate for greater action and awareness around HIV/AIDS.

AfA was also one of the first community groups in Singapore that served the needs of LGBTQ+ individuals—namely men who have sex with men—disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS.

“Back then, people didn’t have as much access to the internet as we do today, meaning that accurate information on HIV/AIDS was much harder to come by, making education efforts vital,” Chan recalled. “On the flip side, no internet meant the gay nightlife scene was more vibrant than what it is today.”

Since the gay community in the 1980s and 1990s did not have the internet and mobile phone apps to meet other people online, they had to go to physical spaces to fulfil their need for connection, whether it was nightlife establishments or cruising grounds.

Gay clubs were hence crucial in AfA’s outreach programs on safe sex practices back in the ’80s—even if it meant risking the possibility of police raids.

Back then, there were very few places in Singapore where gay men felt safe enough to gather in abundance, making gay clubs a viable hub for outreach and education.

AfA’s outreach efforts endure today in the form of the Mobile Testing Van initiative on weekends. The van, parked outside popular gay nightlife spots in Singapore, aims to bring HIV testing closer to the public, bridging the fear and stigma of walking into a stand-alone clinic to get tested.

The Consequence of Outreach

The people brave enough to put themselves out there to serve a larger cause were but a small minority, especially given the cultural milieu of the time.

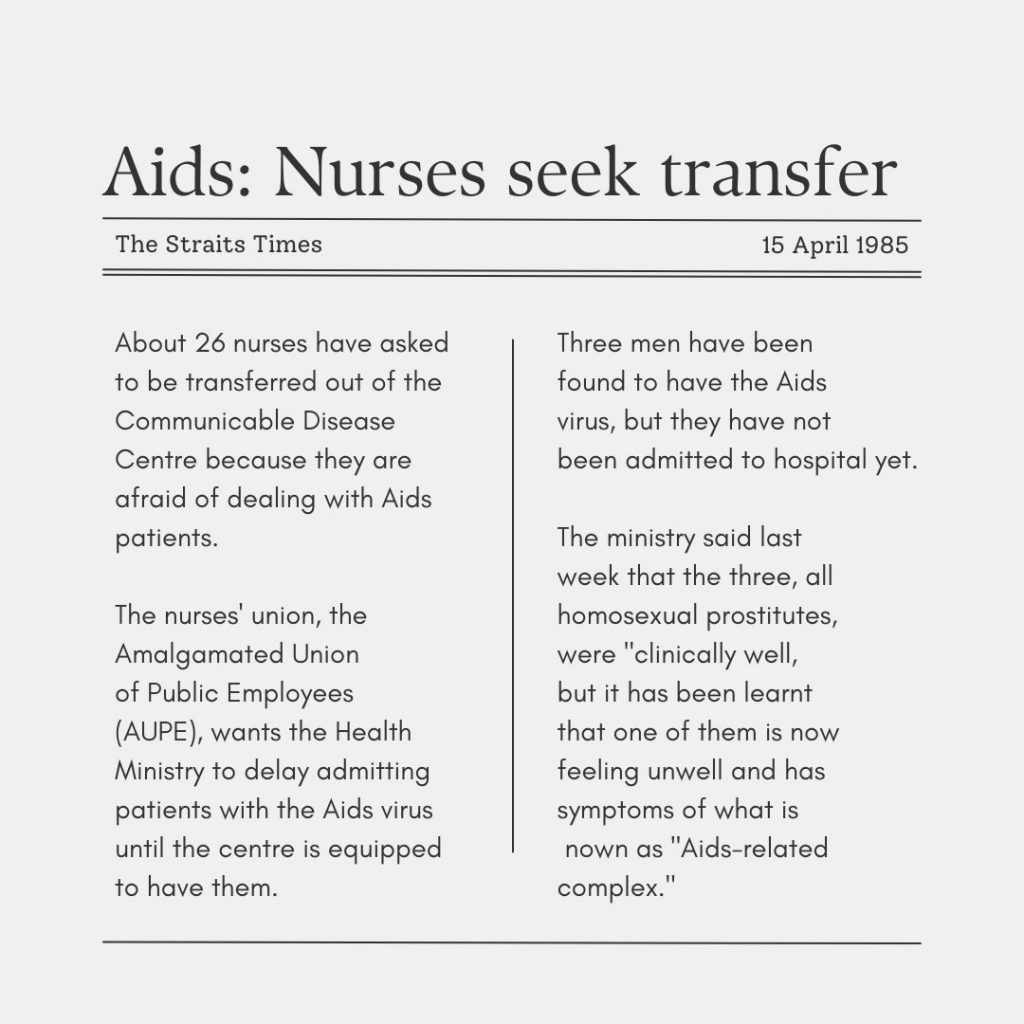

“There was so much that was unknown about HIV/AIDS even among the medical community, much less the general public,” said Verghese.

“Even at Middle Road Hospital, two doctors resigned, and twenty-five nurses asked to be transferred out.”

AfA’s awareness campaigns and fundraiser drives drew a lot of publicity—and no doubt some backlash.

Still, beneath all the headlines and the star power lent by high-profile celebrity allies was the silence surrounding individual HIV/AIDS cases.

“It was all very hush-hush. People didn’t want to talk about it. No one wanted to know who died of AIDS,” Verghese shared when I asked if the atmosphere in the 90s was similar to that depicted in films and drama series such as The Normal Heart and Pose.

The shows portrayed the HIV/AIDS crisis in the disease’s epicentre in New York as being a time of deaths and countless funerals attended by surviving gay men.

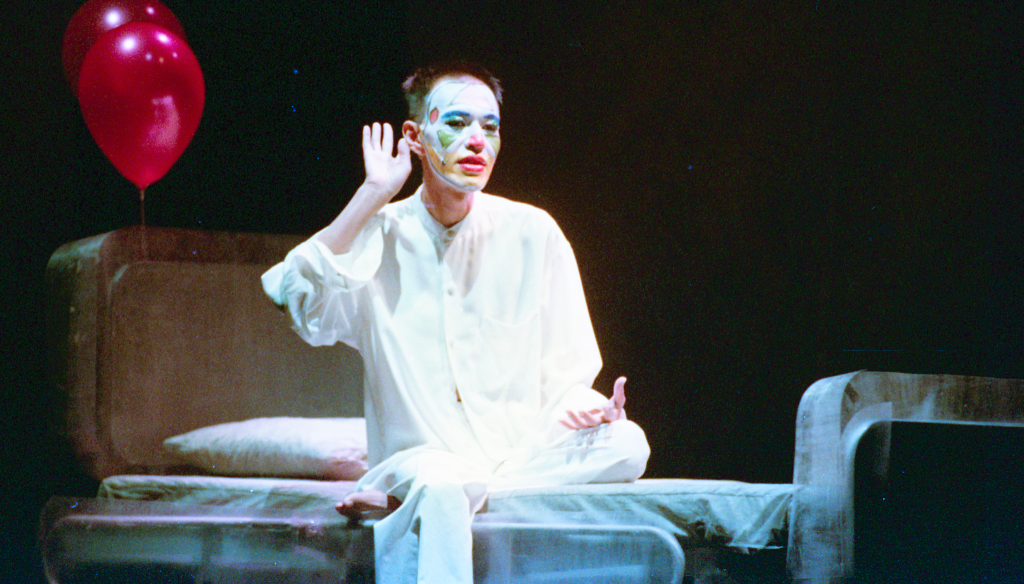

One exception to this veil of silence was Paddy Chew, the first Singaporean person to come out publicly as being a person living with HIV/AIDS.

Chew—well-known for his one-man autobiographical play Completely With/Out Character—told Verghese and her husband that he wanted no crying at his funeral.

“He asked me to arrange his funeral such that his ashes will be thrown into the sea from a Singapore Armed Forces boat,” said Verghese. She and Chew’s close friends were instructed to be dressed in their party best, with helium balloons that were to be released out at sea.

“There was one helium balloon that drifted away from the other balloons. To me, that felt like it was Paddy’s soul saying goodbye to us one last time.”

Paddy Chew’s funeral service in August 1999. He passed away on 21 August 1999. The law at that time mandated that individuals with AIDS be buried or cremated within 24 hours of their death, so his funeral was held the afternoon he passed, with about 80 people present. Images courtesy of Iris Verghese.

A Tale of Two HIV Diagnoses

Perhaps by coincidence—or not, since Verghese was one of the very few nurses dedicated to caring for HIV/AIDS patients at the time—Toh’s then-partner was also one of Verghese’s patients.

“My then-partner Freddie and I handled our HIV diagnoses very differently, but of course, we also came from very different backgrounds and life experiences,” said Toh.

“I found out about my status because an ex-lover of mine had come down with pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP). I flew to Sydney for a diagnosis so that I wouldn’t be registered in the local system here if I was found to be positive.”

On the other hand, Freddie found out about his HIV-positive status because he was a regular blood donor. Not only was his diagnosis inevitably recorded in the national registry, but Freddie also ran into legal trouble. He was charged in court for false disclosure of his sexual activity.

“Because of how the entire trial turned out, Freddie was sentenced to imprisonment for twice the expected duration. It affected his entire outlook in life, feeling like he was being framed by a bigger power with an agenda, with the whole world against him,” said Toh, who cared for Freddie until he passed in 2008.

Toh, on the other hand, took his diagnosis as an opportunity to re-evaluate his life and make the most of the eight years that the doctor told him back in 1989 he had left to live.

“When I received my diagnosis, the only thing in my mind was this: it is the quality of life that matters, not the quantity.” And so, the two spent the next few years of their lives travelling the world, making their remaining years as meaningful as they could be.

Anything for a Chance at Life

Maximising his remaining years did not stop at travel for Toh. Having managed to get his hands on antiretroviral therapy in Sydney in the form of azidothymidine (AZT), he went on to look for more effective forms of medication while the technology was being developed in real-time. Toh wanted to help other HIV patients like himself.

In 1994, Toh joined the Asia Pacific Network of People with HIV/AIDS (APN+), a regional network advocating for the improvement of the lives of people with HIV/AIDS in the Asia-Pacific region, later becoming a Board member and secretariat.

“North America and Europe were progressing swiftly in their battle against HIV/AIDS thanks to the work of activists there putting pressure on their governments and the medical community to channel funding towards the research and development of suitable treatment for HIV/AIDS,” said Toh.

“In Asia, however, it’s a different story. We had to be street smart in our advocacy while also looking elsewhere for allies.”

This meant looking to donors in the West who could be persuaded to recognise the importance of HIV/AIDS advocacy in Asia.

“I was very lucky to have the opportunity to be one of the first few Asians who had access to HAART, said Toh.

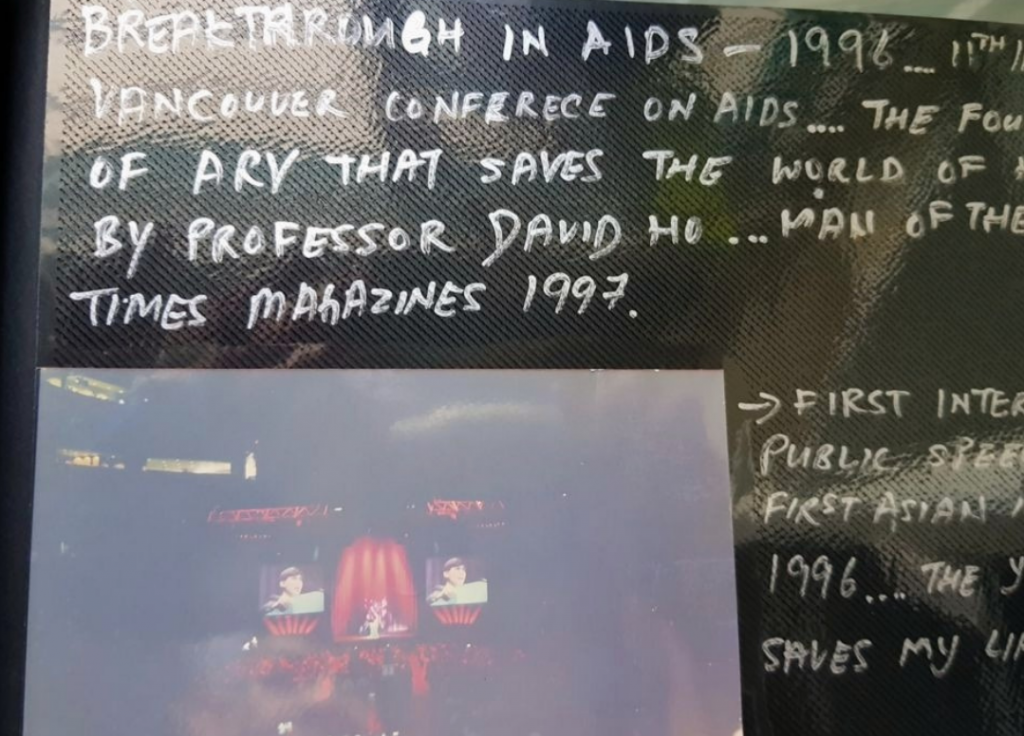

HAART (Highly active antiretroviral therapy) is a triple-combination of antiretroviral drugs discovered in 1996 by Professor David Ho. Toh had been invited to attend the 11th International Conference on AIDS in Vancouver, Canada, where the discovery of this triple cocktail was announced.

Within three months of beginning HAART treatment in 1996, Toh saw his health improving tremendously, with his CD4 count—a measure for the immune system of PLHIV—increasing exponentially and his viral load becoming undetectable within the fourth month.

The eight years he was originally given to live has since become thirty-one and counting.

Although Toh already had a supply of free antiretroviral medication from his healthcare provider in Sydney, he continued to look elsewhere for alternative sources for patients who were unable to afford the patented medication.

“Unlike Taiwan, Hong Kong, and South Korea, where medication for HIV/AIDS was provided to patients for free, Singapore was the only Asian Tiger which did not do so,” said Toh.

“Meanwhile, pharmaceutical companies in developing countries like Brazil, India, and Thailand were manufacturing their own generic antiretroviral medication in spite of patent laws, making it more affordable.”

While still not free, MOH announced in 2020 that HIV medication would become subsidised.

Singapore’s Very Own ‘Buyers Club’

With patented HIV/AIDS medication in the ’80s continuing to be inaccessible to many who needed it, buyers clubs—similar to the one featured in the 2013 film Dallas Buyers Club—would soon emerge worldwide, including Singapore.

“The funny thing was that Australia had easy access to HIV/AIDS medication, so there was a lot of stock available in Sydney,” said Verghese. A family vacation down under in 1987 turned into an informal research trip for her to network and gather the information that she needed to perform her job optimally.

During her trip, she met HIV researcher Dr David Cooper, who brought her to Albion Street Centre (now known as The Albion Centre), which specialises in HIV/AIDS management.

Through her newfound contacts, Verghese managed to get her hands on some of the unused stocks of medication in Sydney back to Singapore for her support group.

“We even got the help of the Singapore Airlines flight attendants to pool together their unused baggage allowance to bring this medication back,” she recounted with a laugh.

Antiretroviral medication was not the only asset that Verghese brought back. She learned a lot about the virus from the professionals she met in Sydney, allowing her to move faster than the national response and gather the information needed to tend to her patients.

A Ground Up Initiative

“George Yeo was actually very impressed with what we were doing,” recounted Verghese. “He wanted to meet with the community to learn more about our efforts and arranged a closed-door meeting with us.”

The meeting was the culmination of months of sending letters to Yeo, the Minister of Health at the time. The dialogue session was held to discuss the government’s rule that mandated the bodies of AIDS sufferers to be buried or cremated within twenty-four hours of dying.

This rule was finally lifted in December 2000, after four years of advocacy by AfA.

They argued that the policy was outdated, having been implemented in the mid-1980s when hardly anything was known about HIV/AIDS.

“I think we’ve certainly had to prove ourselves as an organisation over the years,” Chan said. “There might have been concerns among some who thought of us as a gay rights organisation, or misconceptions that AfA worked solely on issues that concern gay people.”

“But we’ve proven ourselves over the years to be a serious and effective organisation tackling HIV/AIDS and sexual health with clear metrics of success, and the results and continued support from the government speak for themselves,” added Prof Chan.

Toh, who served as AfA’s Executive Director from 2007-2009, concurs.

“Actually, not many people know this, but MOH has been quite supportive of AfA over the years. Even during my term, they would hold closed-door discussions with us, intently wanting to work with us on eliminating HIV/AIDS,” said Toh. He reckoned that MOH did not want to be publicly seen as supporting something considered by society as ‘morally corrupt’ no matter how beneficial it is to wider society.

The Fruits of Our Predecessors’ Labour Are Not Handed on a Silver Plate

The history of HIV/AIDS and its role in fomenting community-building among the LGBTQ+ community has always been a topic of fascination for me.

I can only imagine what it must have been like to see everyone in your social circles and communities succumbing, one by one, to an unknown disease.

Covid-19 provided the closest representation of the tumultuous and uncertain time in the ’80s.

In the midst of writing this, however, the comparison became a much closer one. Monkeypox is now affecting men who have sex with men more than the rest of the general population.

“It’s not the same thing,” Chan said, cautioning against making blanket comparisons between monkeypox and HIV/AIDS.

“For starters,” he intoned, “monkeypox is not an unknown disease. We’ve known about monkeypox for decades, so it is nothing close to HIV back in the ’80s.”

Admittedly, life is easier for a gay man like me, who came of age at a time when HIV/AIDS is no longer considered a significant threat.

With common knowledge of medication as well as preventative measures like safer sex and pre and post-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP and PEP), it is easy for me and my peers to take for granted the freedoms that we now enjoy, thanks to decades of advocacy and destigmatisation.

But as Prof Chan said, “It is important not to be complacent. The freedoms and advancements we have today were not handed on a silver platter. Earlier generations had to fight very hard for all of these things.”