Top image: Kimberly Lim for RICE Media

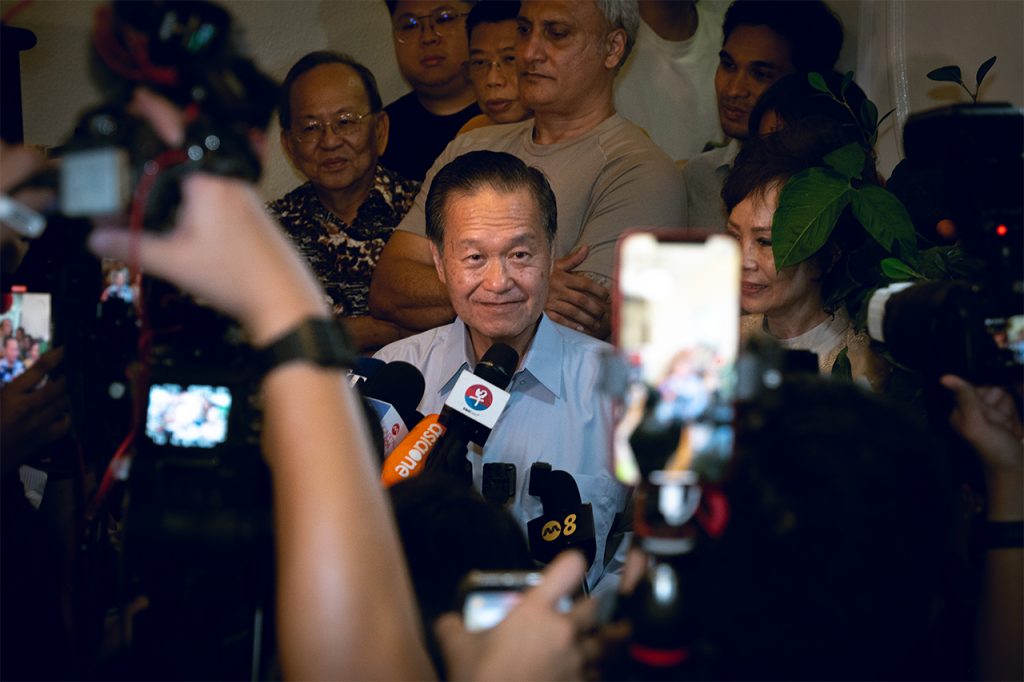

Politics in Singapore are rarely unpredictable—and today, it has proved the same. Former Senior Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam is the nation’s ninth President after emerging victorious in the first contested presidential election in over a decade.

The 66-year-old will become Singapore’s head of state after winning 70.4 percent of the votes—a devastatingly decisive margin.

The signs were there. After scoring a dominant lead for the sample count, he scored 1,746,427 out of over 2.7 million eligible votes.

His rivals were left trailing behind in the dust of the seasoned campaigner. Former GIC chief investment officer Ng Kok Song conceded hours before confirming 15.72 percent of the votes. Former NTUC Income CEO Tan Kin Lian secured 13.88 percent—his second miss at the seat after a disastrous loss in the 2011 elections.

A Not-so-Bumpy Road

Mr Tharman’s triumph follows a (largely) drama-free day at the polls. Aside from a small hiccup at polling stations in the opening hours of voting due to technical issues, the rest of the day went pretty smoothly from 10 AM onwards.

The new president’s rise to the highest office in the land, on the other hand, was smoother. After 22 years in politics—many of them in various ministerial positions—he stepped down from the People’s Action Party (PAP) and entered the race as the firm favourite to win. He was, after all, the candidate endorsed by the ruling government.

And win he did, to no one’s surprise—and a landslide victory at that.

Was this outcome ever in question? Not really. Mr Tharman’s track record is too long to list, but as “one of the best economic minds in Singapore”, he is largely credited as one of the key architects behind Singapore’s current status as a financial hub. He has performed well multiple times representing Singapore on the global stage. This, on top of his other contributions in moving the government a little more left in social policies.

Of course, all his successes in public service remain rooted in his ties to the establishment. Despite Mr Tharman’s resignation from the PAP—and his assertions that he is his “own man“—his impartiality was always in question.

Compared to his competitors, he intentionally veered away from politicking in his presidential campaign. Instead of focusing on non-partisanship (like Mr Ng) or independence from the establishment (like Mr Tan), his focal point was empathy—empathy in multicultural relations, empathy in democracy, and empathy for those clinging on the lower rungs of society’s ladder. Unity despite differences, he affirms.

The Man Behind Tharman

Notably, Mr Tharman had to shed his privacy to endear himself to Singaporeans throughout his campaign. The erudite mind of an articulate statesman had to quickly adapt to the tabloidy nature of scoring brownie points with voters.

And if we’re looking at the phenomenal results, he did well.

As a Senior Minister, he had the luxury of being guarded about his personal life and his opinions. As someone who ran for president, the man spoke candidly about his brushes with racism, his thoughts about social activism, and the need to reform elitist culture in schools. He reached into his past to speak about his passions in sports and poetry.

Then there were the trivial, non-essential factoids the masses demanded: his cats, his cranial luminosity, his love for Jay Chou, and the love story with his wife Jane Yumiko Ittogi.

As far as his family goes, things got a bit too close for comfort. Gutzy Asia, an online publication that describes itself as a Taiwan-based media company, raised questions over Mr Tharman’s son’s appointment in the Ministry of Finance (MOF).

Citing public service directory Contact.gov, the publication asked why Akilan Shanmugaratnam, who works at MOF, seems to have moved from a role dealing with Singapore’s reserves to one in social programmes.

MOF and the Public Service Commission (PSC) have since clarified that Akilan was redesignated in July precisely to avoid any potential conflicts of interest between his work and his father’s presidential candidacy.

In a rare show of heightened emotions, Mr Tharman called the allegations “stray bullets”.

“How about my daughter and my mother and my sister or anyone like that?” he replies to a query about having to declare his relationship with his son to the Elections Department.

“There has to be a purpose, right? There should be some conflict of interest. So if there’s no conflict of interest, it’s a simple matter. This is an utterly straightforward issue.”

Beyond Race

Surprisingly, in a contest between an Indian man and two older Chinese men, Mr Tharman’s ethnicity was not a deciding factor. His track record, extensive experience on the ground, and the relative lack of bad press proved to be more than enough to convince Singaporeans to vote him in as head of state.

Race is a factor in politics, he acknowledged, but the voters of today are looking beyond that.

“I think with each half-decade, Singapore is changing and evolving and I hope that my being elected President is seen as another milestone in that process of evolution,” Mr Tharman mentions.

It didn’t need to be said but on a very basic level, a candidate of an ethnic minority would still face some resistance when competing against other candidates from the majority community.

Perhaps Mr Tharman knew that he would have to win over a segment of the population that includes ethnicity in the equation. The pineapple symbolism (“Ong Lai!”) and that whole calligraphy thing are deliberate enough to be noticed as nods to the majority Chinese community.

Nonetheless, Singapore is ready for a non-Chinese Prime Minister, Mr Tharman believes. His mind will be missed as the most popular prospect for the country’s first Prime Minister of minority descent.

But we’ll take him as President. And the first time (since Benjamin Sheares and Yeo Seh Geok Sheares in 1971) the portraits of Singapore’s President and the President’s partner will feature an interracial couple.