Growing up in a traditional Cantonese family in Singapore, egg tarts were the highlight of dim sum brunches with my folks.

Sweet, fragrant and delicate egg custard in a crispy layered pastry crust, the egg tart, or dan taht as we call it in Cantonese, was a sweet treat we always looked forward to at the end of the meal, paired with a refreshing Chinese tea. There was always room for dessert at the dim sum table.

While many other Singaporeans know egg tarts to be a staple of neighbourhood bakeries, few know that the egg tart’s Cantonese name is actually a combination of two languages. Dan is Cantonese for egg, while taht is an adaptation of the English word ‘tart’.

And so, not only do egg tarts in Singapore represent a melting pot of cultures and flavours, they also tell stories of our beginnings as a country of immigrants.

The first ever egg tart was made in a monastery in Lisbon, Portugal. Portuguese settlers later brought the pastéis de nata pastry with them to the colony of Macau, and the recipe was modified by the British in the 1980s to give Macau’s Portuguese egg tart, or poh taht, its creamy egg custard and signature salty crust.

The Hong Kong dan taht comes in two types of crust. The first type is a butter-based shortcrust that resembles the British egg custard tart; the other is a flaky puff pastry made with oil or lard.

The origins of the Hong Kong egg tart are unclear. But what we do know is it became a menu staple at cha chaan teng in the 1950s – all-day diners offering Western-influenced and Cantonese dishes which are a testament to Hong Kong’s unique status as a gateway between the East and West.

Taking inspiration from English fruit tarts, local chefs improvised on the Chinese egg pudding (a sweet dessert made the same way as the savoury Chinese steamed egg), and created the Cantonese egg tart.

This sparked a great deal of imitation, and eventually with a wave of migration due to political unrest in China during the 1910s and 20s, the Cantonese egg tart travelled south to Hong Kong and Southeast Asia.

One of these Chinese migrants was Mr Fong Chee Heng, a Chinese man from Guangdong province who arrived in Singapore in the late 1910s.

Starting off as a push cart hawker selling egg tarts and other Chinese pastries, Mr Fong worked his way to finally opening a shop in Chinatown’s Smith Street, which he named Tong Heng, meaning “Opulence of the Orient” in Chinese.

Ana, Mr Fong’s great-granddaughter, tells me that her aunts saw great potential in their egg tarts, and wanted to make it Tong Heng’s signature item. They started off with standardising the shape of the pastry.

“Back in my grandfather’s day, they made egg tarts in whatever moulds they had. There were diamond, round, oval and even triangular egg tarts for sale.”

Ana’s business-savvy aunts chose the diamond shape for its distinctive look, and because it was easiest to pack into boxes. As no one was making similar egg tarts back then, the diamond shape of Tong Heng’s egg tarts became its unique brand identity.

For the crust, lard is used, instead of butter or oil, for its “distinct aroma”. To me, it has the familiar taste of traditional Chinese pastries such as red or green bean paste pastry.

The lack of dairy ingredients like milk and cream also makes a difference. Instead of the creamier egg tarts I am accustomed to, the egg custard filling is smooth, sweet and light on the palate.

In fact, Tong Heng’s egg tarts are sweeter than many others I have tasted.

Ana explains, “In China, egg tarts were considered a dessert pastry. It was often paired with Chinese tea, which complements the sweetness.”

In 1965, the year of Singapore’s independence, Balmoral Bakery opened its doors along a row of British restaurants and pubs in Holland Village, where Fosters Steakhouse remains today.

The chief baker, Mr Lim Ming Noong, is in his early 70s. He has been baking since his teens, when Balmoral bakery was opened by his mother and family.

They were first-generation Hainanese immigrants who came to Singapore in the 1920s, and worked for the British and wealthy Peranakans traders. Many Hainanese dishes we have today take early influences from British and Nyonya cuisines.

Balmoral Bakery’s egg tarts, which Mr Lim and his family say is “Hainanese-style”, took its influence from British egg custard tarts, with abundant creamy filling and a biscuit-like shortcrust.

Indeed, Balmoral Bakery’s egg tarts has the most generous filling out of all the egg tarts I’ve tasted for this story. It’s like eating an egg pudding instead of a tart pastry because the custard is about to overflow. Moreover, they only cost $1.40 each.

Generous like his egg tarts, Mr Lim has done his best not to raise prices in spite of inflation. “The rich will find it cheap, but the poor has to be able to afford it,” he says.

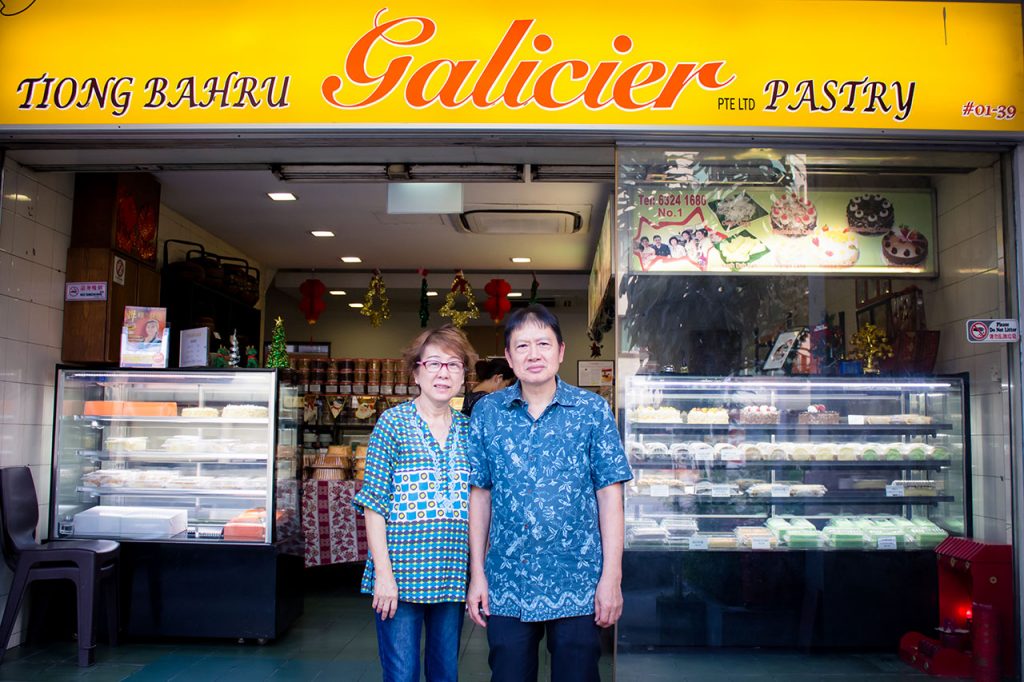

Stepping into Galicier Pastry can be confusing for first-timers. On one side of the bakery, there is an assortment of English Christmas fruit cake, mixed fruit tarts and ladyfingers (known as sponge fingers by the British).

On the other end, Jenny and her family are gathered around the table making traditional nyonya kuehs like putu ayu, a pandan and coconut kueh.

The egg tarts sold in Galicier Pastry today are baked from an original recipe from Jenny’s father, who opened a shop selling traditional English pastries and cakes along Orchard Road in the 1950s.

I taste the difference when I try the crust pastry, which melts in the mouth like an English butter cookie.

As Jenny introduces me to more pastries and kuehs with passion, I see, smell and taste two very old worlds coexisting in a corner shop in Tiong Bahru.

The weight of history is the final ingredient in the flavours that have been passed down from one generation to the next, like heirlooms and precious memories.

So much more than a delicious dim sum, the egg tart has given me a humbling glimpse into the journeys of our grandfathers and great-grandfathers.