All images by Xue Qi Ow Yeong for RICE Media

You don’t normally go to Tai Seng unless you have a very specific reason to. This nondescript industrial estate isn’t even known for being boring (sorry, Yew Tee). Like Jurong Island or Farrer Road, Tai Seng doesn’t cross the average Singaporean’s mind all that often.

“Even in the Google age, there is nothing to be found on Tai Seng,” Ann Phua, the co-author of Once Upon A Tai Seng Village once said.

Thanks to her book, we can glean a little more information about this sleepy district—a former village where gangs, crime, and fights were rampant. Gang wars provided residents with dinner-time entertainment. Taxi drivers refused to enter the district at night.

But like many areas in Singapore, it was eventually cleaned up. Tai Seng began transitioning into an industrial area when government resettlement efforts forced the village’s 15,000 people to move away. The slow exodus took place from 1977 to 1999.

The area saw big names move in and set up factories: DHL, Charles & Keith, and Breadtalk.

Among these illustrious neighbours is a sedated building often overlooked by those not in the know: the Kapo Factory Building.

Kapo has stood at the same spot since it was completed sometime in the tail end of the ‘70s. Throughout the years, this freehold space hasn’t really made headlines, save for a failed acquisition by Hotel Royal Limited in 1991. According to a 1977 property advertisement in The Straits Times, the building’s biggest draw was its… ample car parking spaces.

It was only in my quest to develop some film that I stumbled upon Kapo—a little-known gem boasting an eclectic mix of stores that would make any hipster’s dreams come true.

But beyond the quirky commonalities lies a commitment to preserve Singapore’s cultural heritage from both past and present. In sleepy Tai Seng, of all places.

Treasure At Home (Block B, #06-13B)

If there’s one thing the stores in this story have in common, it’s that they seem to fit better in a quaint shophouse rather than a factory building flanked by hardware storehouses and interior design companies.

Back in the ‘60s, Singapore was a hotbed for labour-intensive industrialisation. Over the years, though, we’ve shifted from low-cost production to high-value manufacturing. Industrial areas— once thought of as ‘ulu’ or out of the way—have also taken on a cool shine these days.

In addition to the usual manufacturing company suspects, you’re just as likely to find local creatives and small quirky outfits populating these buildings.

Our first stop at Kapo is Treasure At Home, a vintage store that’s in the business of nostalgia.

The first thing that greets Treasure At Home’s customers is a teak and glass shop display window from Lumly Motors. Lady boss Aryana, 45, tells me it’s from the 1950s when phone numbers in Singapore only had five digits.

Solid wood furniture and knickknacks fill the room. It almost feels like a museum of sorts—except you can buy the little pieces of Singapore’s history and bring them home.

I feel like checking out absolutely everything, but my attention can’t help drifting to the presidential portraits lining the walls.

Owner Wak Sadri, a former policeman, proudly tells me that it’s taken 15 years to gather all of them in one room. The 46-year-old’s collection is nearly complete, but he’s still looking for portraits of Madam President Halimah Yacob and the late President S.R. Nathan.

Part of the joy is in the searching, though, he says. By seeking out treasures from a bygone era, Sadri and Yana hope to keep their memories alive.

“Sometimes the younger generation doesn’t know who Benjamin Sheares was,” Sadri offers. “What was he working as before he became president? What does he look like?”

I admit that our second president’s name isn’t that unfamiliar, thanks to Benjamin Sheares Bridge and Sheares Hall at the National University of Singapore. But his face isn’t something you’d see often.

Sadri jokes that our most recognisable president might be Yusof Ishak because his visage is emblazoned on our money. He just wants people to remember other forefathers and their spouses too.

“It’s about education. It’s about remembrance. It’s about the good things they have done. They didn’t become presidents for nothing.”

Driven by this sentiment, Sadri also curates a collection of PAP memorabilia: yellowed cadre cards, vintage posters advocating ‘Progress with PAP’, and even painted blinds. He believes it’s vital to preserve the memory of the party’s contributions during Singapore’s formative years.

“Whether people agree or don’t agree, or whether they support them—doesn’t matter. This is history.”

That’s not to say he or his collections are partisan in nature. I spot an autographed poster of a young Tan Cheng Bock grinning from behind a Kickapoo placard.

Funnily enough, the couple lives in the Tai Seng area, so they’d passed by Kapo for years before deciding to set up a store here last year. When they were looking for a place to expand their home-based business, they’d considered shophouses in more central areas. But rental would have been too expensive, and they wouldn’t be able to price their items affordably.

Sadri jokes that he used to find the building ugly, but it was love at first sight when they dropped by to view the unit. Yana loved that it looked like it hadn’t been touched in decades.

She brings my attention to the fan switches in the shop. I’d given them a cursory glance and assumed they were just a collection of antique switches. But the yellowed switches—featuring the cursive Chinese scrawls of previous occupants—turned out to be the original ones that came with the unit.

“When we got the unit, they asked if I wanted to update the switches. I told them: ‘Please don’t touch it,’” she chuckles.

Despite how hidden it is, the store still gets its fair share of regular customers who come week after week to peruse Wak Sadri’s and Yana’s new finds. Some are searching for reminders of their childhood. Some are youngins enamoured with artefacts before their time. Tourists have gotten wind of the place, too—some hail from as far as Switzerland.

“They actually come all the way here to buy a tray and take a picture. I mean, it’s beautiful.”

Red Point Record Warehouse (Block B, #06-11)

Sadri tells me to check out Red Point Record Warehouse, located on the same floor.

The last time my colleagues spoke to owner Ong Chai Koon, who’s in his sixties, he had 70,000 records. Two years since, he tells me the number is now closer to 100,000.

For lovers of all things vintage and analogue, the proximity of the two stores is a beautiful coincidence.

The modest unit is packed from floor to ceiling with music across various genres, from Chinese Orchestra to ‘80s disco. There’s also a sizeable collection of cassettes, CDs, and even mini CDs. I don’t remember seeing them in my childhood, but apparently, these were made to fit in the pockets of sound system salesmen who needed to demonstrate the capabilities of their wares in the ‘90s, he explains.

The former carpenter and former Hi-Fi system salesman is shy when my photographer Xue Qi and I first enter the store but opens up after playing us some Cantonese jams. He still doesn’t want his face photographed, though.

“This one is a bit uncouth,” he warns. His eyes disappear into a friendly smile as we nod along to a song about a jaunt in Geylang.

Like Wak Sadri, Uncle Ong is in the business of preserving memories. A Paymaster ribbon writer with yellowed keys sits on his countertop beside a rotary phone. Just adjacent is a vintage Marantz Hi-Fi stereo and cassette player.

He’d discovered his love for music while selling Hi-Fi systems—he listens to anything and everything, he says—and slowly made the transition to sourcing and selling vinyl records.

Even though he can’t pick his top genre or artist, Uncle Ong lights up when he plays us Hokkien and Cantonese dance beats from the ‘70s and ‘80s. It’s clear he does have favourites.

When he first arrived at Kapo Factory Building some 25 years ago, he’d used the space as a workshop for his woodworking projects, dedicating a small corner to his vinyl records. Over the years, his collection grew, and more customers began returning just for his music offerings.

Today, the place has also become something of a cult favourite hotspot for youths and DJs to hunt for vinyl.

“I began to wonder, could I sustain myself with this business? I tried it out, and it worked.”

What sets his store apart is the sheer number of records he has, he says, and how much local music he carries. The collection that he’s spread out on the countertop for us to peruse spans languages and dialects. I don’t recognise most of it, but Uncle Ong patiently introduces the artists like Ronnie and The Stylers, which used to play at popular club Celestial Room in the ‘60s, and The Travellers, a pop rock band from the ‘70s.

“I’m happy when I get to introduce Singapore’s music to DJs from overseas, and they bring it back to play in their discos.”

As an old-timer in Kapo, he says it’s gotten “more elevated” over the years. Rather than just factories and warehouses, there are more offices there nowadays. Some companies even use the warehouses for livestream sales, he says, not to mention stores like Treasure at Home that have popped up.

“Times are different. Renting at a shopping mall is too expensive, so people have to find a way to survive.”

I get the vibe that he’s not too perturbed by all of the changes in Kapo, though. He’s just content to remain in this music haven he’s created.

Open Door Store (Block B, #01-16)

After spending way too long sifting through vinyl records, we head to our next stop, Open Door Store. It’s on the ground floor, so we pass by trucks unloading their wares and grizzled uncles in polo shirts scowling at nothing in particular.

When we step into Open Door Store, though, we’re back in artsy territory.

At first glance, it looks more like a plant store. Greenery frames the shop’s entrance and cascades down from the cosy loft where they display their merchandise.

“We started with one plant, and then this just happened,” says Open Door Store co-founder Goh Zhong Ming, 37.

Contrary to what it looks like, Open Door Store is not a plant store. Its first floor is taken up by Konstrukt Laboratories, a silkscreen printing house started by Zhong Ming and co-founder Debbie Lee, 33.

On the second floor is a storefront reminiscent of old-school mama shops and racks of apparel—most of which are printed in-house by Zhong Ming. Here, you’ll find apparel from small local brands like New World Plaza and Those’Good’Fellas. Debbie, who used to work in human resources, takes care of the business and marketing side of things.

If the space feels organic, with its exposed wood pallets and foldable chairs, it’s because it wasn’t planned.

Zhong Ming and Debbie were urgently looking for a new warehouse space when the lease for their Geylang Road studio was expiring last June, and this unit at Kapo was one of the last places they saw. They decided to snap it up. It was meant to just be a workshop and storage space.

Zhong Ming has long been passionate about local brands—he used to run an apparel store in Cineleisure over 10 years ago—and always wants to do more for them.

“There are a lot of creative and talented individuals. It’s just that we don’t have a platform here. We only get to see them two or three times a year when there are fairs.”

It’s an uphill battle to get items stocked in local retail stores. And after hearing their clients’ grouses, Zhong Ming and Debbie realised they could offer up their space.

So they hatched the idea of converting their stock area into a retail corner where their clients and local artists could sell their T-shirts and other wares like accessories, art prints, and zines.

“We thought it was going to be a total flop. We didn’t even dare tell our brands to stock up much at the start,” says Zhong Ming.

But the retail concept took flight when they officially opened their doors in June 2023. It was partly thanks to a TikTok video taken by their artist friend, JZ Ang.

They’d invited JZ and a few other friends to the store and he’d randomly decided to promote them by making a TikTok.

“He filmed, edited it, and posted it in, like, five minutes. We carried on drinking, and the next thing we knew, we were getting views and comments.”

News of Open Door Store got picked up by several lifestyle publications like The Smart Local and Vogue Singapore, and business has been brisk ever since.

Their core goal is to get more locals to shop local brands, which has become a reality. They’ve also been shining the spotlight on more homegrown artists with initiatives such as Pools Project. The “for fun T-shirt project”, a collaboration with illustrator John Fan, which involves getting artists to create their own shirt design.

Tourists have even gotten wind of them, says Zhong Ming. They’re always happy to introduce local artists to foreigners—even directing customers to their Kapo neighbours, Red Point Record Warehouse and Treasure At Home.

“Somehow or rather, we must be doing something right for international tourists to come by,” Zhong Ming remarks.

“We get Malaysians, Indonesians, Taiwanese, Japanese. Sometimes, even Europeans. Can you imagine? Europeans coming to Tai Seng?”

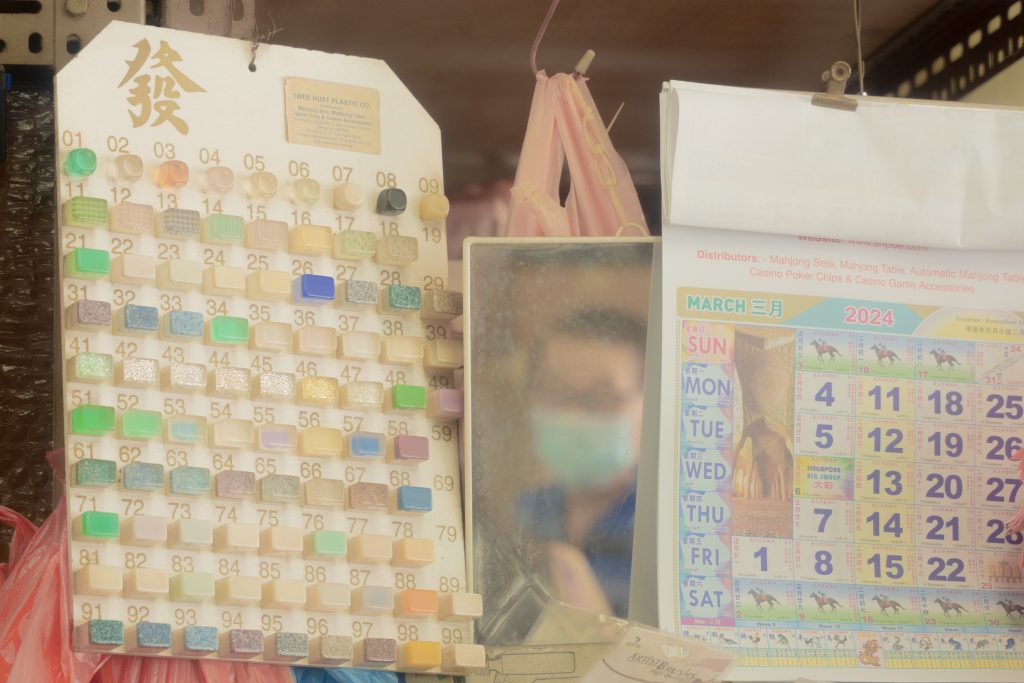

Swee Huat Plastic Co. (Block B, #04-18)

Industrial estates aren’t exactly set up for browsing. If it weren’t for the recommendations of my other interviewees, I wouldn’t have known about Swee Huat, one of Singapore’s oldest mahjong tile retailers.

Established in 1975 (49 years ago!), it started out selling mahjong tiles handmade in-house. Now, it sells imported tiles as technological advances mean that machine-made tiles are much easier to churn out, founder Mr Lau tells me.

Glass cabinets showcase their tiles, which come in a dizzying array of colours and finishes. An adorably tiny set with tiles half the usual size catches my eye. These mini sets (called ‘travel mahjong’) are made to be light and portable so you can play anywhere, says the 76-year-old.

“When did you come to Kapo?” I ask.

Mr Lau takes a moment to sieve through his memories to recall the exact year: 1986. A workshop corner remains in the shop, reminiscent of the old days when they made mahjong tiles by hand. An old Chinese tune plays in the background as a metal industrial fan whirrs.

The elderly craftsman warms up to our presence as he shows us the tools of his trade. The metal tools are aged and black—maybe a little dusty—but still functional. One contraption holds the mahjong tiles in place while another engraves the design on them. Another box on the table holds an assortment of slides with the different mahjong suits.

It’s not as common as it was before, he says, but he still breaks out the old tools whenever customers need minor repairs, such as replacing a missing tile in their mahjong set.

“I learnt the art of mahjong tile-making in Malaysia when I was young. Of course, when I came back to Singapore, I opened a store. What else would I do?” he says matter-of-factly.

He’s similarly realistic when I ask about the footfall in this relatively ulu building. Google advertisements have served him well, he tells me.

“These days, people are very good at Googling. We even get young people coming to buy mahjong tiles.”

Indeed, as reported by The Straits Times in 2021, more young people are embracing this “old man’s game”. As nostalgia and tradition gain traction as trendy pursuits, it’s not unusual to see millennials and Gen Zs coming together for a round of mahjong beyond CNY gatherings.

Seeking Refuge in All Things Old

This intentional return to analogue might also explain the popularity of some of the other stores in this building. As we search for some respite from tech fatigue, more are ditching smartphones for dumbphones. Film cameras and old digital cameras have seen a resurgence. Vinyl records have long had a small group of loyal fans (“for that old-school hiss and warm sound”, a colleague says), but they’ve also made a bigger comeback in the past decade.

There’s also something calming about browsing a quiet record store or checking out a heritage business on your downtime instead of squeezing in with the ever-growing crowds in malls or other tired tourist hot spots. Plus, making a trip to Tai Seng feels like an event in itself—an adventure in a quiet industrial district.

It does seem serendipitous that all of these interesting businesses ended up in the Kapo Factory Building, but the more I chat with these retailers, the more it becomes clear that they’re here out of necessity—a concerted effort to keep their unconventional businesses afloat by keeping costs low.

In this enclave, disparate shops coalesce around a common ethos, providing a serene escape from the urban bustle. The peeling paint and squatting toilets only enhance the charm, evoking a sense of stepping back into Singapore’s unvarnished past. Though Tai Seng’s gang wars have long faded, vestiges of the past linger as Singaporeans both young and old strive to safeguard our authentic heritage.