But despite The T Project’s charitable function, Chua has been unable to register the organisation as a non-profit. She tried to register in September last year and got rejected. In September this year, Member of Parliament Lam Pin Min wrote an appeal letter for her.

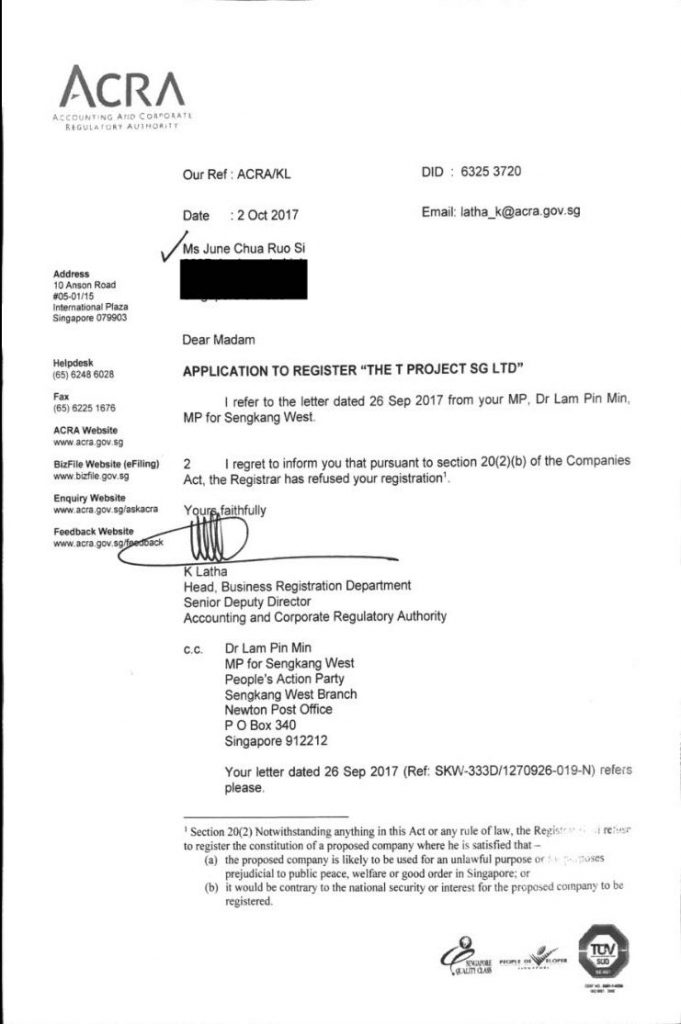

On Oct 2, the Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority (ACRA) rejected the appeal, saying the registrar has “refused your registration”.

This means The T Project has missed out on opportunities, such as when a company promises to do a dollar for dollar matching for money raised by an employee. There have also been cases where companies had already done the fundraising only to hit a roadblock when it came to transferring the money to The T Project.

Chua declined to name the companies, but estimates that there is about $14,000 “stuck” until she gets a corporate account.

Said Chua: “Because of corporate governance issues, companies cannot disburse funds to personal accounts.”

“Just $10,000 can sustain us for a few months,” she adds.

As such, for the past three years, The T Project has had to sustain its operations on personal donations simply because Chua could not open a corporate banking account.

In the latest letter from ACRA, the authority cited 20(2)(b) of the Companies Act as a reason why the registration was refused.

(a) the proposed company is likely to be used for an unlawful purpose or for purposes prejudicial to public peace, welfare or good order in Singapore; or

(b) it would be contrary to the national security or interest for the proposed company to be registered.

Rice has reached out to ACRA for comment on why a transgender shelter registering as a non-profit would be contrary to national security or interest, and is still waiting for a response. Chua said she could register as a business, but that meant spending funds on taxes on top of the rent she pays for the shophouse in the eastern part of Singapore.

Criminal and commercial lawyer Suang Wijaya from Eugene Thuraisingam LLP said that in terms of options, Chua does not have many.

She could register as a society or a charity, but “like the Registrar of Companies, the Registrar of Societies and the Commissioner of Charities similarly have the power to refuse registration of a society or charity on the basis that such registration would be contrary to the national interest”.

He also said that Chua could appeal to the Minister for Finance within 30 days of the notification of the Registrar’s decision, and if that appeal is dismissed, she can file a judicial review application in the High Court.

But Wijaya said these are uphill tasks.

“If there is no evidence to show that a decision-maker had acted in bad faith, courts (both in Singapore and other common law jurisdictions) generally give relevant decision-makers wide latitude in matters concerning national security or interests.

“In other words, even if the court disagrees with the decision-maker’s determination on a national security or interest concern, the court will likely still be slow to overrule the decision-maker. This is because it is well-recognised that issues of national security or what is in the national interest are best left to policymakers, not judges.”

It is unclear if The T Project was rejected for its work in the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community, but similarly in 1997, LGBT lobby group People Like Us failed in its bid to register as a society.

Chua shares that the $137,000 she raised from the public last September is now down to an amount that will let the shelter survive for less than a year.

With this money, The T Project has already set up a board and due processes. New clients have been referred by social workers from various family service centres and healthcare facilities, and they have received care from both social workers and professional counsellors. The registration of The T Project is just another part of this due process that Chua wants to add.

“I want to give donors more confidence that we are a legitimate organisation. Even for personal donors, I want to give them peace of mind.”