All images by Janine Choo and Ilyas Sholihyn for Rice Media unless otherwise stated.

I’m kneeling with my head bowed and feeling a tad self-conscious. “Good afternoon, everyone,” I chirp alongside my colleague, Eudea.

People are seated around me in pairs, either sitting cross-legged on the floor with someone kneeling behind them or sitting on plastic chairs facing each other.

With every pair, one person has their hand raised, hovering over an area of their partner’s body. In some ways (many, in fact), it looks like a generic spiritual gathering.

But for a smattering of online Facebook and Reddit users, everyone here at the Singapore chapter of the Japanese group, Sukyo Mahikari, belongs to a cult.

“One of the frightening many cults in Japan. They hang around my area sometimes with their newspaper professing the doom of the world, and you can only be saved by giving them money.”

/r/japanlife/Sukyo Mahikari Thread

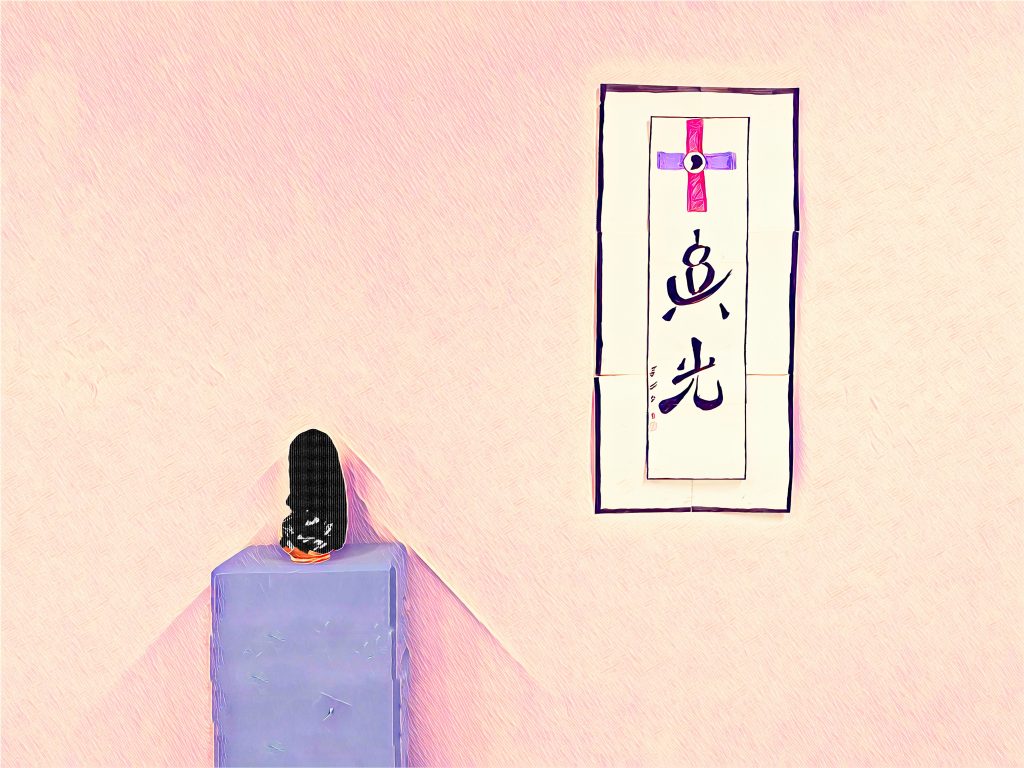

The room we’re in is spacious and neat, housing minimal decor and sporting traditional tatami mat flooring—unmistakably Japanese in aesthetics. My eyes drift to the altar, which takes up the entire wall at one end of the room.

It’s a simple set-up, with a scroll bearing a cross and a small statue (which I find out is the material God of Sukyo Mahikari) on a tall pedestal. The wall on the other end of the room is plastered with posters that detail the various teachings of Sukyo Mahikari.

“Good afternoon,” a chorus of voices politely replied from behind masked faces. I later learn that they were performing the okiyome rites or ‘giving light’—a kind of healing practice that is a cornerstone of the controversial group.

This practice of ‘giving light’, which can take anywhere from 10 minutes to an hour, is one of the most significant practices of Sukyo Mahikari, as I’m told by Betty*, a young practitioner in her early twenties.

She became our bridge into the inner workings of this enigmatic organisation.

The Perplexing (and Cult-y) World of Sukyo Mahikari

It’s not hard to infiltrate cults since they are always on the lookout for new members. This applies to groups that are characterised and labelled as one, like Sukyo Mahikari.

A call citing membership interest from Eudea to its Singapore headquarters got us attached to Betty. Which is how we found ourselves at Guilin Building in Geylang one sweltering Sunday afternoon.

According to their website, Sukyo Mahikari is marketed as a “non-profit religious organisation” for licensing reasons.

Their site explains that Sukyo Mahikari’s principles are common to most religions and encompass all the universal truths of people’s relationship with God. New members don’t have to renounce their current faith (Abrahamic or not) to be part of Sukyo Mahikari.

This openness and criteria are at odds with many mainstream religions of singular faith and practice.

It could be that Sukyo Mahikari considers themselves supra religious, meaning they intend to transcend religion and be unbounded by any limits of mainstream religion.

As such, members can be Christian or Buddhist and a member of Sukyo Mahikari as well, Betty explains at a nearby coffee shop a little earlier that day.

‘The Art of True Light‘

Despite being a third-year university student, Betty seems a lot younger than she looks.

Sporting a simple green t-shirt, round glasses, and hair pulled up in a scrunchie, she could easily pass for a student studying for her A-levels.

A little shy at first, Betty introduces herself and her commitment to the dojo (what they call the spiritual centre) over a plate of basil pork fried rice. Having been inducted into the group by her mother, she is now an active member of Sukyo Mahikari.

Betty is, in every way, your good Mahikari Girl.

Her weekends are spent at the centre, where she is heavily involved in youth activities and run-of-the-mill bonding pursuits, from watching movies to playing Captain’s Ball. She has already gone through a training course to ‘give light’ (more on this later).

She’s even planning a trip (read: pilgrimage) to Japan to visit Mahikari’s Main World Shrine in Takayama, a Sukyo Mahikari equivalent of Muslims going to Mecca.

Knowledgeable about all things Sukyo Mahikari, Betty explains how the group believes God’s ‘light’ is the spiritual energy or vibration of God’s wisdom, love, and will. She tells us in earnest that this ‘light’ exists throughout the universe and is the fundamental power that creates and sustains life. Betty speaks of Sukyo Mahikari’s teachings with an air of dutifulness and devotion—characteristic of anyone devoted to dogma.

As such, the act of receiving ‘light’ is a practice of purifying the spiritual, astral, and physical realms with the energy and power of the highest God. This ‘light’ is seen as a healing factor, supposedly capable of assisting with ailments, aches, and pains.

A huge and confusing caveat to this? Sukyo Mahikari believes that a disease is 20 percent physical and 80 percent ‘spiritual disturbances’, such as clingy spirits, bad karma, or if you are just a negative Nancy in general.

As such, according to Sukyo Mahikari, medical science should be focused on solving ‘spiritual disturbances’. Instead of, you know, cancer and the like.

Phew. That was a lot.

The Healing ‘Light’ of Sukyo Mahikari

Betty shares with us her scoliosis diagnosis. With the unusual curvature of her spine comes frequent backaches and painful period cramps.

Her mother was the first person to give her ‘light’ for her cramps. After this procedure, Betty claims her cramps were soothed and the aches in her back lessened.

“Of course, we do not stop you from going to the doctor or taking medicine,” she says abruptly to Eudea and me, almost as if she’d been reciting from a script.

The more she benefited from the ‘light’, the more Betty immersed herself into Sukyo Mahikari and its community. After all, she tells us, this process of ‘receiving light’ is a two-way process. Those who don’t try or learn to ‘give light’ are frowned upon.

Religions are all about give-and-take anyway, with a slight emphasis on the give.

Betty attended a three-day Kenshu, a spiritual developmental course where members would learn how to radiate this True Light. After the training, they would have a religious pendant called omitama.

According to many exposé blogs, it’s a simple piece of jewellery—a chain with a gold medallion bearing the star of David enclosing a piece of paper with the Su God symbol.

It is quite a sacred object, says Betty, and no one is allowed to see the omitama, so it is kept hidden and close to the heart (literally, the omitama is worn under clothes and kept close to the chest through sewn pockets).

At this point, I’m unsure how one gives or receives ‘light’, but something tells me I’m about to find out.

Betty checks her watch. It’s time for us to head to the dojo.

To Cult or Not to Cult

As we wind through the bustling thoroughfares of Geylang, I cannot help but remark on how tame Sukyo Mahikari seems—at least from Betty’s point of view. Also, the whole ‘giving light’ portion might be a touch far-fetched. I wonder how the ‘light’ fared against the darkness of Covid.

Still, if anything, Sukyo Mahikari can be parked under a New Age religion of sorts, given its relatively short history. The founder, Okada Yoshikazu, claimed to be the Second Messiah through a divine possession by God, with a mission to cleanse the world. Sukyo Mahikari is also preparing for a Baptism by Fire (aka doomsday) that would forge a new spirit-centred civilization. The prophesied dates shift quite a bit.

However, a casual search on Google reveals a more unsavoury—and even dangerous—side to Sukyo Mahikari. This can be inferred from their anti-Semitic teachings, rewritings of history, and storied list of survival accounts condemning the group as a cult.

Former members accuse it of manipulating, exploiting its members, and perpetuating harmful, possibly life-threatening ideologies. One of its darker beliefs is how Western medicine is evil, and a surgical procedure contributes to your ‘spiritual impurities’.

There are also alleged ties of Sukyo Mahikari’s members to the dangerous Japanese terrorist cult, Aum Shinrikyo. Even though this connection remains unverified.

Given the renewed interest in cults and all things cult-like, it’s hard to call Sukyo Mahikari an actual cult with such limited access to information.

Not to mention, we (meaning the Internet) might have been playing fast and loose with the definition of a cult. Many things like spinning, Marvel and Star Wars fandoms, and an overzealous interest in dumpling bags have gained cult status. Can it be argued that enthusiasts behave like they are in a cult?

In these instances, there is a certain fanaticism to their behaviour. There is specialised jargon and buzzwords (think: Trekkies, activation, ‘higher self’, and so on) that are often tagged to a charismatic leader. Varying degrees of so-called exploitation range from buying expensive merch to waiting in line for hours to catch a new release, or being peer-pressured into buying a hyped-up spin bike.

With Sukyo Mahikari’s dubious reputation, highly questionable teachings, the wide-eyed innocence of Betty, and half a million members worldwide as of the latest count, you can’t help but think that this group checks all the boxes.

And while there are damning accounts of practices of Sukyo Mahikari peppering the Internet at every turn, some comments and Reddit threads describe the group as relatively benign and not as sinister as they are made to be.

Some commenters from regional and local groups categorise Sukyo Mahikari as “reiki but more organised”.

Still, as they say, seeing is believing. I am a visual journalist, after all.

The Ritual Before the ‘Light‘

The Singapore branch of Sukyo Mahikari resides in the unsuspecting, commercial Guilin Building. It’s not the first place you think of when it comes to receiving or experiencing divinity.

For newcomers to Sukyo Mahkari, the best way to experience what the group has to offer is by receiving ‘light’.

We take the lift to the fourth floor of the Guilin Building. All the while, Betty nods and greets members who are leaving or going for their Sunday afternoon session. As the lift doors open, I realise that Sukyo Mahikari occupies nearly the entire level.

But before we can receive ‘light’, we must take a few steps to prepare ourselves.

A raised tiled floor leads us to a small cloakroom, where we leave our shoes in a designated shoe rack. We continue along them to the kitchen and pantry area, where there’s a large sink with soap dispensers at our disposal to wash our hands.

In between scrubbing, I notice a bulletin board nearby replete with dojo activities—from their latest youth gathering reminders to the dates of their Kenshu courses.

So far, nothing as sinister as the blogs say.

First Impressions and Greetings

For a religion with roots in Japan, a country known for its homogenous culture, the members of the Singaporean branch are startlingly diverse.

There are members of different races—including Caucasians—of different ages, from as young as 10 to middle-aged adults. When we arrive at the main prayer room, it’s quiet for the most part, with only whispers and hushed tones rippling through the silence.

Before we can receive ‘light’, we must pay our respects to Su-no-kami-sama, the creator god called Su God and the material god displayed at the end of the room.

Betty smiles and quietly beckons us to follow her lead.

We walk to the front of the altar, kneel to face the Su God, right hand over left, and begin with two bows, followed by three sharp claps, another bow and four sharp claps. All in sync.

Now to the statue Izunome-sama, the deity representing the materialisation of spiritual energy, Betty explains.

We turn to face the statue, bow once and offer no claps. After this, we move to the back of the room to greet everyone already there. The ritual can now begin.

Receiving ‘Light’

According to some of the Sukyo Mahikari readings, divine ‘light’ exists all around us. But the dojo would have the highest amount of ‘light’—which is why the practice of okiyome is said to be most effective there.

The process is simple; one ‘receives light’ from the palm of their hand with the giver’s back facing the altar.

Betty will ‘give me light’. Eudea, being the special Japanophile she is, will receive ‘light’ from the head Doshi (leader) hailing from Japan.

“Betty says he gives better ‘light’,” Eudea tells me later. Perhaps a little too proudly, almost swishing her hair.

I’m instructed to sit in a kneeling position, eyes closed. Betty has her back facing the altar and chants the Amatsu Norigoto prayer, holding her hand about 30 centimetres from my face.

Gokubi jisso gengen shikai Taka-amahara ni kamu tamahi moe-ide-masu

Kamurogi Kamuromi no michikara mochite Bansei to hito no mioya kamu amatsu su no mahikari ohomikami harahido no okami-tachi Moro-moro no sakagoto tamahi no tsu-tsumi kigare o ba mahikari mote harahi kiyome misogi tamaite Kami no ko no chikara yomigaerase tamae to mosu koto no yoshi o Kashikomi kashikomi mo maosu

Mioya motosu mahikari oho-mikami mamori tama-e sakiha-e tama-e

Mioya motosu mahikari oho-mikami mamori tama-e sakiha-e tama-e

Kan-nagara tamahi chi ha-i mase

Kan-nagara tamahi chi ha-i mase

This process lasted 10 minutes. I was already feeling a little light-headed, having my eyes closed and not moving. My ankles began to protest, and I feel the tingling pins and needles creeping up my toes.

Close to the end, she chants the Oshizukani prayer (where the phrase oshizukani is chanted three times) meant to ward off any spirits that overwhelm the body. This chanting happens in succession with other pairs in the room, making it sound like a bizarre series of incantations.

Betty begins to focus the ‘light’ on my ‘problem’ areas—mostly my back and abdomen. Typical writer’s ailment, you know how it is.

Betty is engrossed in her task and hovers her hand over specific parts of my body as dictated by the okiyome zone chart at the back of the room.

Diseases are not exactly recognised in Sukyo Mahikari; instead, everyone has ‘spiritual impurities’. The purging of these spiritual impurities emerges as ‘illnesses’. As such, by receiving ‘light’, one would feel much better.

Still, as efficacious as this ‘light’ might sound, it has to be ‘received’ regularly for the full effect.

I want to say I felt something after those 50 minutes of healing, but I can’t attest to walking out of the room feeling any different from when I walked in. Eudea concurs, noting that she has been here to receive the ‘light’ previously and still feels unchanged.

She adds wryly she might have gotten even more headaches out of it. Clearly, the ‘light’ hasn’t diminished her sass.

Betty then walks us to the lift and waves goodbye, mentioning it’s her turn to receive ‘light’ while she awaits her mother in the evening. We never see each other again.

Is Sukyo Mahikari A Cult?

For such a secretive religion as Sukyo Mahikari, we would have loved to hear more from Betty, other members, or even the head Doshi themselves.

However, they declined further interview requests, citing the capriciousness and unpredictability of the media and the internet. They fear that more people might misunderstand their practices or deface their sacred objects.

For now, the group (at least the one in Singapore) remains shrouded behind exposé blogs and articles that continually paint them in an unflattering light.

Still, one shouldn’t dismiss any of the harrowing experiences narrated online about Sukyo Mahikari. The experience we had in our limited time, however, seems relatively benign and harmless—there was no overt coercion on their part, and members seem pretty happy to be there.

We’ve only gleaned the surface of this faction of Sukyo Mahikari because that’s what we could get and were offered. The jury is still out whether the Singapore version of Sukyo Mahikari can be considered a cult, or whether they are just a discreet New Age religion.

At most, it is an alternative religion that just… exists. It’s harmless and, if anything, a display of unconventional ‘healing’ that is less invasive than, say, chiropractic treatments.

As of now, I don’t think I can confidently classify Sukyo Mahikari as a cult, at least from my short two days of experience. Beyond the healing ‘light’, perhaps the greatest benefit Betty derives from Sukyo Mahikari is a strong sense of community, belonging, and even a higher purpose. Which many would agree is the function of most religions, anyway.

As controversial as the group is if these practices seem to benefit these people and—to the best of our knowledge—not hurt anyone, who am I to judge?