All images by Zachary Tang for RICE Media.

The first thing that greets you the moment you enter the living room of Mae’s Farrer Park HDB flat is the sheer number of items set out. The house settles briefly from the decluttering and reorganizing process currently underway for us to meet.

83-year-old Mae and 69-year-old Terrie sit amongst a treasure trove of brown exercise books, stationery, tchotchkes, artworks, decorative vases of porcelain, and crystal that line almost every surface.

But in this home, there is clearly great care for the items gathered in this seemingly disorganised scene. Notebooks are neatly stacked and in their place. Stationery is tucked into holders nearby. Decorative porcelain nick-nacks are displayed proudly on shelves by the television for all to see.

It’s impossible to stay hooked on one item when there’s a smorgasbord of things to look at. Your attention is drawn from one interesting bauble to the next, finding beauty hidden in the visual clutter. Then just as quickly, your gaze is drawn rapidly to the next sparkle.

The visual texture of the home makes it impossible for one’s attention to stay fixed on one item for long. For Mae and Terrie, who has Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD), this feeling is a familiar one.

Aunty Mae’s Notebook

Mae and Terrie are two of the lucky ones. Mae is a few years shy of 90, but her eyes still shine with a steely vigour. She lives alone in her flat—completely independent, of course.

Throughout the interview, she refers to a notebook filled with her thoughts penned in flowing letters with bold red ink. Colour-coding her notes and calendars helps her keep track of the little details in her life, which she finds hard to remember.

Yet, as Singapore’s oldest property agent, she is able to regale thrilling stories of selling apartments— complete with an uncanny memory for dates, locations, and prices.

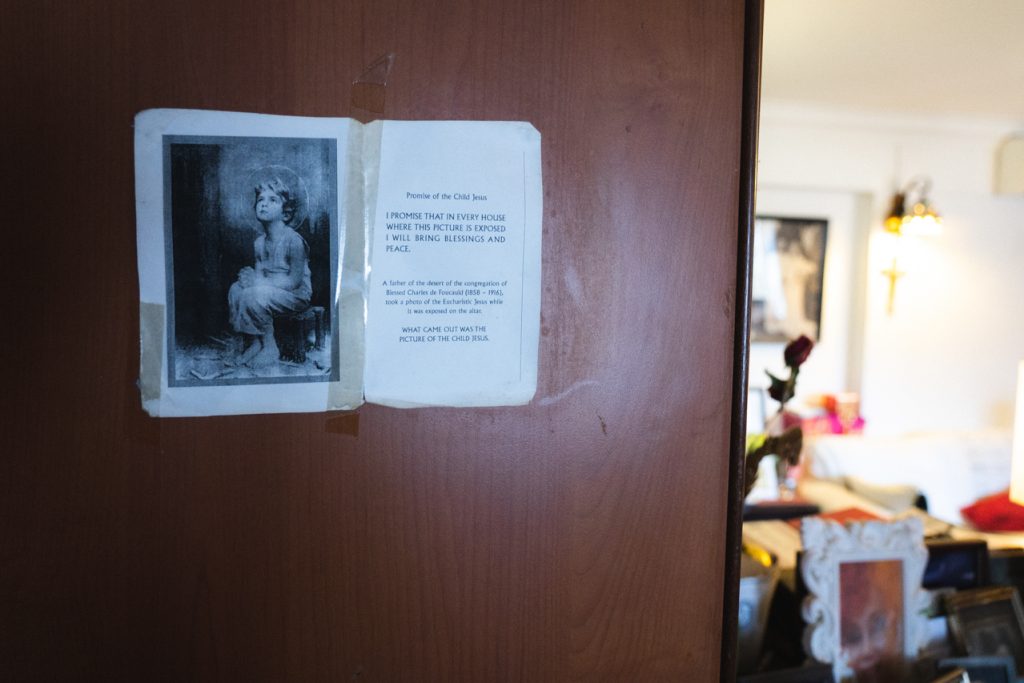

The discussion then shifts from the topic of ADHD to her time during the Japanese Occupation, to her Catholic faith, to her time studying in a convent with the Infant Jesus Sisters.

Then we jump back to how she had trouble focusing in school—religion and careful note-taking helped her pull through classes and excel.

“The headmistress of my school taught us how to serve. Like ladies, you know? She didn’t want us talking to the boys. We listened to [Felix] Mendelsohn while polishing silverware. That started my love of classical music. But I know I wanted to be Catholic. I wanted to be a nun.”

The topic then meanders to the varied opportunities she desperately wanted to pursue but denied herself.

“I wanted to go to a movie. I had the ticket, and I was about to set out for the theatre. But at the last minute, I stopped. I denied myself,” she shares.

This arbitrary stream of consciousness is all par for the course. Mae has ADHD, and it shows. For Mae, her faith, willpower and set routines in the convent school helped her manage her ADHD symptoms.

Despite that, she has come far. She has nine grandchildren whom she helped raise. She listens to lectures over Zoom and browses the internet often to catch up on political news. And she absolutely refuses to retire.

ADHD: Not Just a Childhood Issue

Not long before this interview, Mae was tested for ADHD and Mild Cognitive Impairment. Her results revealed that she leaned more towards ADHD.

For children, ADHD symptoms (constant fidgeting, excessive talking, interrupting conversations, inattention, forgetfulness, and carelessness, amongst many others) are the source of behavioural issues, low self-esteem, and poor academic performance.

Carried over into adulthood, these symptoms can result in higher smoking rates, poor performance at work, and can lead to depression or anxiety.

Mae’s condition is still being investigated to establish a baseline to observe the symptoms for the possibility of treatment. Moonlake Lee, the 53-year-old founder of Unlocking ADHD, says awareness that Mae might have ADHD is important, even if she is not formally diagnosed. It helps the family adjust their support.

“ADHD is not just a childhood issue, but one that carries over into the Golden Years,” Moonlake shares.

Moonlake is Mae’s niece. She was diagnosed with ADHD in her 50s, right after her teenage daughter’s own diagnosis. ADHD runs in the family, all the way back to Mae’s generation.

Aunty Terrie’s Various Fancies

Terrie, far more laid back, chats from her strategically-chosen seat under the cool stream of the air conditioner. Her voice is resonant and full of life as she shares her story.

Terrie lives with her husband and two tenants—her children have long since flown the coop. Professionally, she found her niche in a successful corporate executive career in sales and public relations.

Now happily retired, Terrie busies herself with volunteer work and enjoys spending time with her two sons and four grandchildren.

She shares Mae’s lifelong penchant for hobby-hopping, moving quickly from one interest to the next.

Each new passion burns with a fiery intensity before fizzling out when her curiosity is sated. Then, she finds something else to replace it.

Humour and warmth resonate in Terrie’s voice as she speaks of the times when ADHD interfered with her school life. She was often smacked on the head in class for not paying attention and scolded for interrupting her teacher in class discussions. Her thoughts speed by a hundred miles a minute—her mouth moves even faster.

“Can you let me finish?” Terrie exclaims, then grins at my stunned expression. “People say that because I keep on interrupting. I think it’s a trait, even for Mae.” Her hearty laugh fills the room.

‘I don’t have dementia‘

Terrie identified that she had ADHD when her second son was diagnosed.

“My son likes contact time with me. He comes and he’s telling his story. Then I also want to tell my story, so I interrupt him. Then he will say, ‘Mummy, can you let me finish my story first?’ It’s happened more than once.”

She was initially tested for dementia due to her forgetfulness, but the test turned out negative.

This only served to confirm her suspicions that it was ADHD.

“I asked for an ADHD report, but the test seems the same. They scan your brain. But [the doctor] gave me a report that says I don’t have dementia.”

She decided not to pursue a formal diagnosis and focused on self-managing her symptoms now that she is more confident about her condition. Knowing the condition helps give seniors like Terrie a sense of awareness about themselves.

It also enables families to improve their relationships with a mutual understanding of why their seniors behave the way they do.

Marie Kondo for the Mind

These coping strategies for the elderly and their families are one way of managing ADHD symptoms in lieu of medication or a formal diagnosis.

Terrie, who also volunteers at Unlocking ADHD, is fully aware of her condition and has learned to manage it independently. Like Mae, she developed her own coping strategies like colour-coding, writing notes, and arriving early for appointments.

These, she feels, help to ease the day-to-day interference her symptoms may cause.

Other cognitive strategies include visualisation of completing tasks big and small, sorting through the day’s random thoughts, and choosing which thought to finish, keep, and discard.

Marie Kondo for the mind, if you will.

Sometimes, even indulging the occasional impulse helps. For Mae, so does prayer. The strength of her faith is one of the key anchors in managing her impulsiveness.

Among the many whims her fickle focus may impose, she has God and prayer to ground her and keep her impulses in check.

“I attribute my willpower to the nuns,” Mae reflects. “You want something very badly, but you deny yourself. When you’re passionate about something, you can go all out to do it. But I can just let it go, you know?”

When asked how she managed to deny the many passions or opportunities that captured her attention, she replies simply, “I procrastinated.”

The Tenuous Work of Diagnosing Elderly ADHD

As someone currently in the process of being diagnosed with ADHD, working on this story couldn’t have come at a better time.

My partner, who was formally diagnosed, saw that the symptoms I have are similar to what she faces.

I was only able to sit down and finish this article in one go because I was hyper-focused on it—it had been 10 hours since I last had food.

When I sat down to write, my brain decided that this article was the only thing that mattered right now, bodily functions be damned.

Before considering I had ADHD, I thought my symptoms showed a character flaw or a lack of basic intelligence to function in simple tasks. Now, I know that’s not the case.

“There’s a label on this condition,” Terrie reminds me.

It doesn’t help that diagnosis for ADHD is more straightforward with children than for adults like me since it’s easier to observe the symptoms. In fact, much of the Clinical Practice Guidelines in Singapore focuses on diagnosing and treating childhood ADHD.

Fidgeting, excessive movements and talking are noticeable symptoms, especially to teachers. Terrie finds herself in good company with this category: “We have so much energy, and we have so many interests.”

Others who show inattentive ADHD symptoms like “spacing out” or constant forgetfulness tend to be diagnosed at a later date.

For adults to be diagnosed, they must show at least five out of nine traits as listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Neuropsychological testing is also available to accompany clinical interviews in the diagnostic process.

Still, the DSM-5 does not fully and adequately address how ADHD manifests in older adults.

“For most adults diagnosed, the biggest thing for them was the feeling of grief for the lost years,” Moonlake intones. “What would life be like if somebody had diagnosed them earlier, or they had the tools to manage life better?”

For seniors far beyond middle age, the lost years might cut even deeper.

ADHD: A Mistaken Identity

In her book, Still Distracted After All These Years: Exploring ADHD after 60, Dr Kathleen Nadeau identifies specific symptoms that present consistently in older adults.

These symptoms include forgetfulness, procrastination, increased irritability or mood disorders, time blindness, failure to stick to a routine, restlessness or talking too much, and feeling judged or missing social cues.

For clinicians, these symptoms are interpreted as the far more familiar conditions of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) or dementia, as in the case of Mae and Terrie, respectively.

Furthermore, age-related cognitive conditions make diagnosing the elderly less conclusive than in children or adults. “ADHD is a complex condition, with many interweaving comorbidities and mental health issues,” says Moonlake. “So it’s not easy to tease out.”

It doesn’t help that age-related cognitive decline, dementia, Alzheimer’s, and MCI often share symptoms with ADHD. Frustratingly, these conditions can also occur alongside ADHD.

It makes the work of separating ADHD symptoms from these comorbid conditions difficult. For a start, both conditions require vastly different treatment approaches. Most times, ADHD symptoms are mitigated by medication.

This presents yet another problem for seniors. In managing physical ailments in addition to their neurological conditions, introducing more medicine can be difficult and dangerous.

‘I am more worried about losing my mind.‘

ADHD was less understood in Mae and Terrie’s youth, so learning of their condition was surprising news to both.

For Mae, neurological testing continues as doctors try to determine whether her symptoms are MCI or ADHD. While the doctors fret, Mae takes it in her stride.

“I didn’t know I had ADHD,” Mae laughs. “I didn’t know what it was all about until I heard from Moon that certain children (in the family) had it, but I didn’t bother about it. I didn’t know what it was.”

Terrie, too, approaches it with a light heart. “I am more worried about dementia and losing my mind,” she says.

Terrie’s light-hearted dismissal and Mae’s ambivalence are likely made possible by their successful coping strategies.

“I have my diary,” Terrie says. “My big A4-sized diary. If I lose it, it’s like losing my mind. I transfer everything there and keep very little in my mind.”

It’s a strategy she has in common with Mae, whose carefully colour-coded calendar notes down everything from doctor appointments to knee pains and mass times.

Are Diagnoses Worth the Effort?

The question remains: Is the diagnosis of ADHD for an older person even worth the time?

In an interview with CNA, Dr Bhanu Gupta, a senior consultant at the Institute of Mental Health’s department of mood and anxiety, said: “Clinicians have a lot of experience and can evaluate symptoms more objectively, as well as ensure that other possible co-existing conditions are ruled out or treated.”

Still, when approached for comment on facts and figures about ADHD—specifically in the elderly— doctors at IMH declined to comment, citing the rarity of its occurrence in their clinic.

Moonlake suspects most elderly with ADHD are left to manage their own symptoms without diagnosis or even considering the possibility of ADHD late in life.

“If a child has ADHD, there is a high chance one or both parents have it. And if they are unaware (of their diagnosis) and therefore unmanaged, how can they hope to support their child successfully?”

The same can be said for adults whose elderly family members might manifest ADHD symptoms. How can one hope to successfully support an elderly if one is unaware of the elder’s full condition?

A lack of education among the elderly and their families is one reason the condition is overlooked. Coupled with the common misconception that ADHD is a childhood problem, it is easy to see why an elder’s constant forgetfulness might be written off as an ageing pain.

“Aiyah, Ah Kong is always like that”; “Nenek always forget to put on her hearing aid”; or “Tatta starts taking his shower only when we’re about to leave the house”. These occurrences might seem harmless, endearing even.

But they may portend a bigger problem which, left unchecked, might make an elderly’s last few decades of living less fulfilling.

Living at Peace With Elderly ADHD

“It’s never too late to get diagnosed. We live on to our eighties and nineties if we take good care of our health, so there are still many decades to live a better life,” Moonlake emphasises.

Presently, Unlocking ADHD is working to reach out to the Silver Generation in all communities. Earlier this year, microsites and webinars were launched with information on ADHD in Malay, Mandarin, and Tamil to enable easier access to vital resources in these languages.

For now, Moonlake believes education is the best way forward. Just because the elderly with ADHD have coped with their symptoms for so long, it should not be assumed that it hasn’t affected them.

“I was very advanced for my age… but I knew we were not as advanced in our learning, so I wanted to be better,” Mae said. “I wanted to try everything. I was determined to learn things. But I felt like I wasn’t smart enough.”

“It was a Eureka moment when I read about it,” Terrie says. “There’s a label on this condition? And then it made sense why I was different from other people.”

Knowledge has armed her with self-awareness, helping her appreciate the condition’s effect on her life.

“In my golden years, I celebrate it.”