Top image: Google Maps

* Names have been changed as teachers are unauthorised to speak to the press

Fancy a $6 discount with minimum spending of $40 at Times Bookshop? Perhaps you’d appreciate a 30 per cent off weekday and weekend rates at Aranda Country Club or a Wild Wild Wet premium membership going at $66 instead of $98.

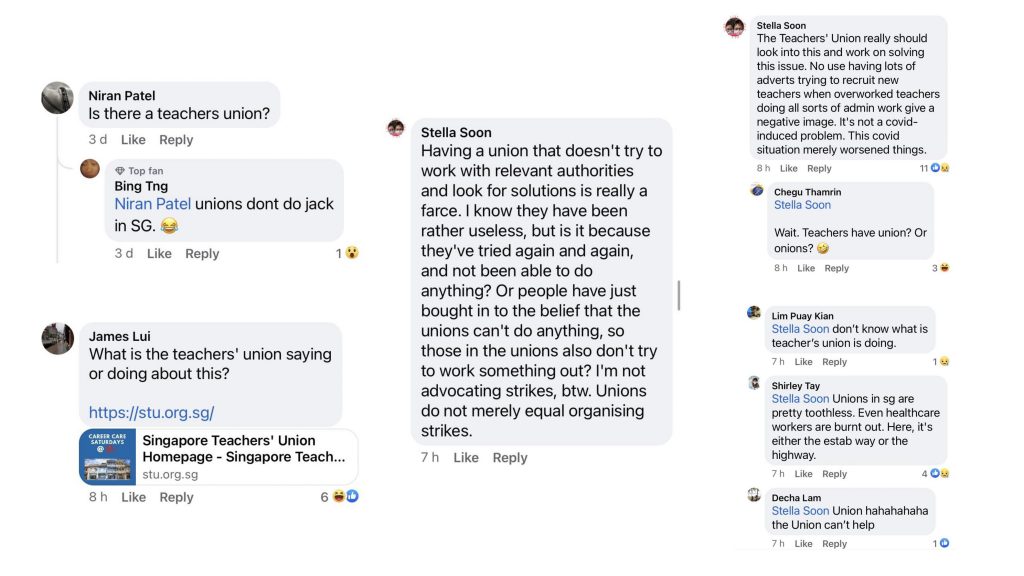

These are some goodies teachers associate with the Singapore Teachers’ Union instead of regarding them as a serious body representing and advocating on their behalf—at least for veteran primary school teacher Lucy*.

She has been a card-carrying union member for more than three decades. Those privileges were part of the package when she registered for an insurance plan years ago.

Given the raison d’etre of a trade union is to represent workers and their interests, it’s puzzling when material benefits first comes to Lucy’s mind when Singapore Teachers’ Union is mentioned, just like how we subconsciously recall the familiar supermarket when the affiliated NTUC (National Trades Union Congress) is brought up.

In a survey commissioned from online market research firm Milieu Insight, we asked 108 teachers to pick three pertinent stakeholders who are most important in ensuring their mental well-being. These teachers work in levels from primary schools to junior colleges with varying years of experience.

Of those surveyed, six per cent picked the union as one of their top three stakeholders. This pales in comparison to the others selected by the teachers—management (92 per cent), reporting officer (57 per cent), and the government (52 per cent).

If one of STU’s missions is to improve the service and working conditions of members, why is it that teachers don’t readily turn to the trade union and get them to lobby for reforms to improve their mental health?

“The union’s hands are tied“

Lucy shared that the STU is not powerful enough to advocate for reforms at the policy level. “When it comes to MOE’s policies, there is nothing much the teachers’ union can do to change things.”

Besides, she felt the best people to approach for work-related issues will be her reporting officer or the school principal, who are generally supportive. Lucy said they are in a better position to advise instead of the union, which is an external agent.

For primary school teacher Grace*, even if she is burnt out, she feels the issues are not serious enough to tap on the union. The Mother Tongue teacher in her 20s said: “Mental health is a very personal problem, how can the union help with it?”

Ditto for Afiq*, 53, who perceives the union as incapable even if he faces burnout or issues in school. He is not a member of Singapore Teachers’ Union.

“If I were in that situation, I would meet a counsellor or psychologist. I don’t think the union can influence the school to lighten the load or stress that the teacher is facing,” said the primary school teacher of 20 years.

One common thread, however, runs through their anecdotes when they shared about the help rendered by STU: assisting teachers in transferring schools when they can no longer tolerate their working environment. This looks like the closest STU gets in functioning like a typical trade union.

Although even in this instance, it’s still unclear how helpful the union is. A teacher we spoke to said some of her colleagues received a poor grade during the performance appraisal and they sought help from STU.

However, the teacher alleged that STU passed the matter back to the school principal—this has since been refuted by the union—which they felt defeated the purpose of them approaching the union in the first place.

“Not surprising”: STU Gen-Sec on survey findings

I spoke to one of the top honchos at STU, Mr Mike Thiruman, for his comments on our findings with Milieu Insight.

The union’s general secretary said he isn’t taken aback, when told that only six per cent of teachers we surveyed thought of STU as the most important stakeholder in ensuring their mental well-being.

“If you ask anyone who can make a difference, it will be the people who impact you then and there, which are obviously the management and reporting officers as the top group because the workload and pressure comes from them.”

Mr Thiruman said he has always emphasised that school leaders are key and they act as a fulcrum—they can either take care of their teachers and ensure their mental well-being, or contribute to their burnout.

This doesn’t mean STU is sitting back doing nothing about the mental wellness of teachers, as perceived by some teachers.

If a burnt-out teacher needs help or a listening ear, for example, they can approach trained counsellors at the union for in-house counselling services.

Mr Thiruman provided some figures: for the past five years, about 24 to 30 teachers approach the STU for its counselling services each year for work-related stress, their ability to cope, and the high expectations themselves and others have of them. He emphasised that this doesn’t mean burnout only affects this small group of people.

When there’s a need to, the union’s counsellors will also persuade those teachers to seek psychiatric help, especially those on the brink but are reluctant to do so, since the union cannot provide them with professional medical assistance.

In fact, before my phone interview with Mr Thiruman, who has a degree in psychology, he was speaking to a teacher who is on hospitalisation leave due to stress. He advised her to focus on recovery first and not to worry about school or her students, and that STU will help her with work-related issues when she is feeling better.

It’s not easy for teachers to come forward, Mr Thiruman admitted. “This is still a hurdle because we come from a generation where seeking help isn’t a norm.”

A more adversarial STU in the past

Teachers whom I chatted with have an impression that STU isn’t helpful in advocating their concerns to the powers that be. But has it been so all along?

A look into the archives would reveal that STU and the government used to share a more adversarial relationship. Salaries and benefits were problems STU actively negotiated with the government. Older teachers might have forgotten these when they romanticised the “good old days” of the 1960s and 70s when teaching was said to be less stressful.

Barely a year after its inception in 1946, the union lobbied the colonial administration to give married female teachers equal rights as other staff in the service.

They called for the abolition of a 1928 ruling where female teachers had to resign upon marriage and re-employed temporarily, for which they were reverted to their initial salaries of $100 and excluded from the provident fund.

In the same year, teachers from the union also fought aggressively for their British bosses to back-pay them for their service during the Japanese Occupation period, making provocative comments and ultimatums to get their way.

A strike was also planned by the union in early 1957 to call for the government to officially include normal-trained teachers—teachers who teach for half a day and undergo training for the second half—in the Education Service. This strike was eventually called off after Mr Chew Swee Kee, the Education Minister then, promised that he would personally negotiate with the union.

Even after independence, the union continued with its activist role and criticised the Education Ministry for its policies at various points.

In 1975, STU jumped on the ministry’s move to shrink the duration for year-end examinations and its subsequent grading of exam papers, because it gave unnecessary stress to students who took the assessment and teachers who had to grade them.

The following year, the union criticised MOE for interfering with school principals’ decisions to grant urgent private affairs leave to teachers, and told the ministry to keep an arms’ length away.

The issue of leave entitlement continued well into 1980, when the union called for the ministry to review its policy on deducting teachers’ no-pay and half-pay leaves from the school holidays.

Parliament also gave STU a platform to voice the concerns of teachers directly to lawmakers, when one of its past presidents, Mr Lawrence Sia Khoon Seong, was an MP for Moulmein constituency from 1968 to 1991.

What happened thereafter?

From the 1980s, the STU appears to have mellowed and not as adversarial as it used to be.

While there isn’t a direct explanation for this shift, a parliamentary speech by Deputy Prime Minister Goh Keng Swee in February 1981 might give us a hint, as he struck deep in the heart of the union’s existence.

Dr Goh suggested that teachers’ unions in Singapore be scrapped and transformed into a professional association instead.

He said: “I see no advantage in the continued existence of the Teachers’ Unions. The ultimate bargaining strength of the trade union is the right to strike.”

But the unions had not organised any strikes and it would be illegal to do so anyway because education is gazetted as an essential service, Dr Goh said.

“It is inconceivable that the PAP (People’s Action Party) government will allow matters to reach such a point that teachers will go on strike—something which happens quite frequently in other countries.”

Although STU continues to exist, Dr Goh’s controversial suggestion could be seen as an implicit warning for the union to downplay its adversarial role.

The writing was already on the wall, as the union was stonewalled by MOE previously whenever it highlighted to them survey findings it conducted among its members and the fraternity.

From then, gone were the union’s scathing editorials of the Education Ministry in its publication The Mentor.

How is STU like today?

Now with a 14,500-strong membership, up from about 12,000 in 2016, the union still gives their occasional two-cents worth publicly.

However, they are usually veiled criticisms, commissioned studies or suggestions, rather than a raw and unburnished attack on the ministry’s policies the way they did in the past.

Its spokespersons now adopt a measured approach and tone when making comments in the press.

In STU’s working relationship with the Education Ministry, there is now greater symbiosis, often negotiating behind the scenes instead of airing dissatisfaction openly. Both parties often present a unified front on issues, with fewer public displays of disaffection.

“Even if we disagree with MOE, it’s done behind closed doors. We would outrightly tell them the problems and that they have to do something about it. We don’t always agree on everything,” said Mr Thiruman, who added that they have championed the mental wellness of teachers with the ministry for some time now.

Perhaps this is why some teachers feel the union has lost its teeth. They might think the union has been co-opted by the government and thus unable to represent teachers effectively.

Worse still, some systemic problems remain unresolved, which further confirms the teachers’ beliefs that STU is an ineffective advocate—even though some issues are deep-seated and take time to iron out, through no fault of STU.

But are these perceptions justified? Ultimately, the proof of the pudding is in the eating. While the union’s advocacy work isn’t widely publicised, it doesn’t mean the STU hasn’t done anything to push for reforms at the ministry level.

Every three months, STU representatives will meet MOE officers to voice their concerns and advocate for improvements to the system. The engagement with MOE has increased in the last two years.

Mr Thiruman shared that during a major meeting in early 2020, both parties talked about the performance ranking, which is a bugbear among teachers—39 per cent of our survey respondents said unfair performance appraisals contributed to burnout.

But before anyone dismisses these ministry-level meetings as “no action, talk only”, it bears mentioning that there were instances when headways were made.

He cited the Allied Educators scheme as an example. The scheme, which started in 2009, trains allied educators to manage students with learning needs and provide other assistance to teachers.

At the risk of sounding like deja vu, it was against the backdrop of the 2003 SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) crisis when STU highlighted to MOE that teachers were overworked and required more help in the classroom.

After discussions with then Education Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam, the union started the Teachers’ Assistants Scheme, where they trained and placed assistants in school to help lighten the classroom workload of teachers.

The ministry also funded schools for them to get more manpower. When the STU’s scheme was proven successful, the ministry later adapted and enhanced it to create today’s Allied Educators scheme.

It’d have been easy for STU to claim victory for such reforms. But it isn’t the union’s working style to beat their chests whenever reforms they propose get through, said Mr Thiruman.

“The focus should be on whether the policy gets carried. A victory is not what we are after. What helps the teacher is what matters.”

Whither the way forward?

STU has a fine line to tread if it wants to remain relevant within the teaching fraternity and increase its prominence as a mental health advocate rather than as a body known better for cheap deals and goodies.

If this Straits Times interview with a trade union leader is of any indication, I wouldn’t be surprised if teachers prefer STU to be more combative with MOE.

Former NTUC president John De Payva said in that interview: “Younger people don’t really want to subscribe to behind-the-scenes hard work. They want us to be transparent and vocal, take nasty employers to task and even tell the Government, ‘This is not enough, you have to do more’.”

In recent months, especially after CNA kicked off the discourse on teachers’ burnout, younger teachers are starting to share their stories of panic attacks and supervisors from hell. Even though they entered the profession with their eyes open, this newer generation of teachers is less likely than their seniors to suck it up and soldier on.

Given how mental health is now the talk of town, it’s timely for STU to jump on this bandwagon and press on with advocating for more concrete reforms.

Already, in light of the upcoming year-end vacation, Mr Thiruman has a suggestion for MOE: let teachers enjoy the full duration of the break. If teachers have to be called back, it should be capped at a maximum of one week.

Yet, it behoves the union to be circumspect and not be overly adversarial. Neither party will benefit—MOE, the union, and teachers—if historical precedence replays and the ministry closes its doors to STU’s feedback. Worse still if a prolonged public spectacle plays out and problems remain unresolved.

It might not be STU’s style to bang the drums on the work they do, but remaining in the shadows will not work if it wants more teachers to approach them for help on mental health issues.

A balance has to be struck. With a little sprucing up on their communications and optics, the union may actually increase their visibility among teachers as the mental wellness advocate they’ve always needed.

RICE readers who are teachers can access these hotlines if they are feeling burnt out:

National Care Hotline: 1800-202-6868 (8AM – 12AM)

Institute of Mental Health’s Mental Health Helpline: 6389-2222 (24 hours)

Samaritans of Singapore: 1800-221-4444 (24 hours) /1-767 (24 hours)

Singapore Association for Mental Health: 1800-283-7019

Silver Ribbon Singapore: 6386-1928

Tinkle Friend: 1800-274-4788 and www.tinklefriend.sg

Community Health Assessment Team: 6493-6500/1 and www.chat.mentalhealth.sg

Counselling services at Singapore Teachers’ Union: 6299-3936