All images by Xue Qi Ow Yeong for RICE Media.

At first glance, Global Village Snack Shop doesn’t stand out among its neighbours at Holland Village Market & Food Centre. Small details, though, set it apart—the fairy lights casting a warm glow on the storefront, the wall of art prints and New Yorker posters, the eclectic assortment of snacks.

The tiny stall—only slightly bigger than an HDB bomb shelter—feels like a supermarket’s exotic food aisle on steroids.

ADVERTISEMENT

It’s where you’ll also find the shopkeeper, Nazish Zafar, a petite woman with a no-nonsense bob. She’s usually tucked in a corner, almost dwarfed by the teeming shelves.

And what vibrant shelves they are—packed with an irresistible medley of niche snacks that feel like passport stamps in edible form. On any given day, you’ll find a unique mix of international nibbles at Global Village: Mints from Czechia, fruit rolls from Ukraine, Polish sauerkraut, beetroot bars from New Zealand, and cassava flour cookies from Indonesia.

At 40, Nazish is considered a young face at Holland Village Market & Food Centre. Her neighbouring tenants are well into their 80s, some of whom have been hawking their wares here for over 50 years, she tells me.

Nazish, however, has only been operating at the market for just under a year.

It was a series of spontaneous decisions that led her from Big Tech—she previously ran Grab’s regional User Experience (UX) research team—to a small market stall selling snacks.

“I was very passionate about research and product strategy. I loved my team. I loved the work we were doing. I loved the chance to improve the product experience for millions of people, so there wasn’t a concrete reason to leave,” Nazish tells me emphatically as we perch on stools at the shop, watching other stall owners bustle around.

But this isn’t your typical story of a burnt out millennial trying to escape the corporate world.

Rather, her unconventional choice was driven by pure, simple intellectual curiosity. Nazish, a sociologist by training with a PhD from John Hopkins University, explains:

“I’ve tried surviving on a modest stipend while doing my PhD. I worked in a start-up. I’ve worked in Big Tech. I’ve published a book about small businesses. But I realised, I haven’t actually tried running one.”

Like many other young people nowadays, she doesn’t see career progression as a ladder, nor is it her goal to make the most money possible. Rather, her priority is to accumulate different reservoirs of life experiences.

As more of us reckon with work and its place in our lives, Nazish offers a glimpse into an alternative path for those of us looking for fulfilment beyond our jobs. She’s not just reconsidering her priorities, she’s trading the glittering cage of corporate success for the raw, unpredictable thrill of starting something from scratch.

ADVERTISEMENT

Hungry for More

Halfway through my conversation with Nazish, an elderly couple shuffle up to the stall to buy some mushroom chips.

“I read that you gave up a high-paying job to do this,” the husband remarks casually, referencing a recent Lianhe Zaobao article on the shop.

“Yes,” Nazish laughs. “But do you think it’s a good decision or bad decision?”

He seems unprepared for the question and murmurs noncommittally as he peruses a jar of roasted chickpeas.

After the couple departs with chips in hand, Nazish tells me that her decision to leave her corporate role at Grab and set up shop in a wet market tends to surprise people. At least, to those who don’t know her well.

Even before her Grab stint, she was no stranger to unconventional career moves. After completing her PhD, she took a job at a small startup, working in social media—a role that some of her friends saw as beneath her.

“A friend said to me, ‘You have a PhD and you’re writing Tweets.’ But to me, I’m learning so much about startups and how they work.”

True enough, what she learned from her startup days helped her when she moved on to work in UX research over at Grab, fine-tuning the user experience of everything from food delivery to merchant solutions.

“I’m bringing that knowledge from the ground into creating products at scale. My point is that they all feed into one another. No job is an end to itself.”

Still, she’s ever the realist. She admits that leaving Grab was one of the toughest decisions she’s had to make in recent memory.

Crunch Time

Her foray into the wet market began in late 2023, when she was chatting with some vendors at a pop-up market.

She’d pulled up the National Environment Agency website to demonstrate how easy it was to bid for a market stall when a listing caught her eye: Holland Village Market & Food Centre. Just a stone’s throw away from her HDB flat, it was the market she’d grown up patronising.

She initially never considered leaving her job at Grab, so she pestered her family to put in a bid for the stall, promising that she’d help out regularly. In her mind, this was the best of both worlds—she’d still be able to work the job she loved, but also occasionally get to be a shopkeeper.

Unfortunately, they, too, were all busy with their own jobs. It was two days before the bidding deadline that she began to seriously consider putting in a bid herself.

She recounts her thought process: “If I don’t win it, life goes on. If I win it, I can decide later. So what’s the harm in bidding?”

The real dilemma came when she won the bid with a rent below $1,000. She was on a sabbatical from Grab at the time, so it wasn’t an immediate decision, but she knew she would eventually have to pick either the stall or her full-time job.

There was no way to do both. It was a choice between stability and uncertainty; the job she loved and the chance to start something new from scratch.

In the end, what really helped her decide was a simple time management trick called timeboxing. In timeboxing, you allot a specific amount of time to a certain task. The idea is to avoid distractions and hone in on that one task for the allotted time.

“Everything can be timeboxed. After resigning, I decided to give myself a year to work on this stall. It’s just one year in your life. Who cares? What is one year? Who’s going to remember?”

I think about how ever since I’ve entered the working world, time just seems to fly by—you blink and suddenly you’re at the end of another year. Truly, what’s one year out of all the decades of our lives we’re spending in the workforce?

Nazish does, however, relay a word of caution from two of her customers who also left their corporate jobs.

“YOLO (you only live once), but with your seatbelt on.”

Essentially, it means this: Pursue your passion, but don’t forget about earning a living.

She admits that she seriously considered the financial consequences of her decision. But, unsurprisingly, she has a refreshing way of looking at it.

“I’d ask: how much does it cost to do an MBA (Master of Business Administration)? I’m gaining business wisdom without the same expense and debt. This perspective helps me reframe the risk.”

It also helps that she’s not a big spender. She only has one pair of sneakers, mostly uses free tote bags, and has been spending less on commuting since she lives near the shop, she says.

The traditional Singaporean dream of landing a ‘good job’ and FIRE-ing has also never really resonated with her. Since she was young, she’d had the goal of contributing to society in a meaningful way, either at scale (for example, through tech) or in a focused manner (say, teaching). Growing up, she says, she thought of becoming a doctor. But sociology won her over.

“The liberal arts background probably plays into it,” she offers as an explanation as to why she’s never really been fussed about money or status.

Nazish says she’s still shaping Global Village Snack Shop into a financially sustainable business. Meanwhile, she’s supplementing her income by doing consulting work on the side. In fact, she’s extra productive when she works from her shop, which she sees as her unofficial office space.

Even though she’s not earning as much as she did in her Big Tech days, I get the sense that she’s content with the life she’s built for herself.

Market Stalls: A Hidden Gem (for Real)

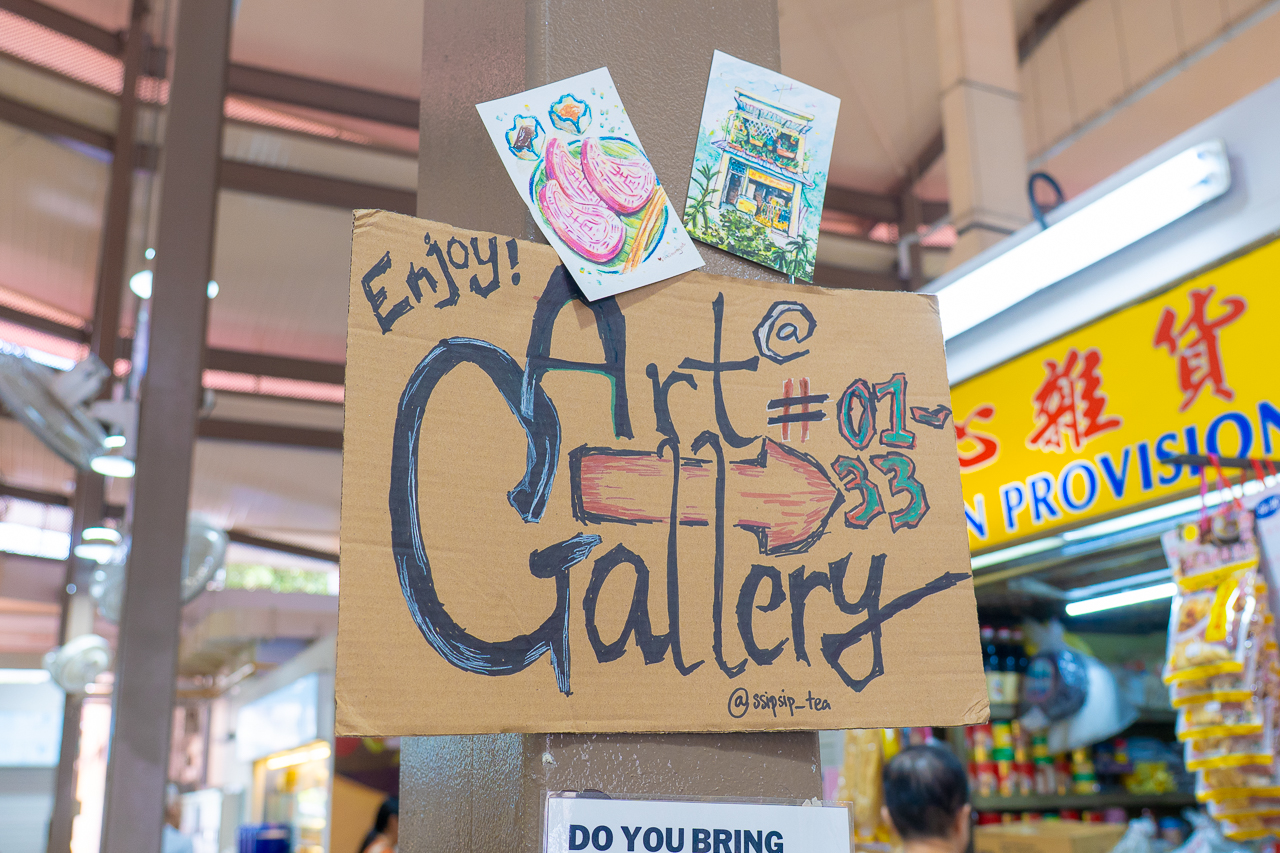

Eleven months ago, Nazish’s shop was a tiny, barren box. Today, it’s a warm, welcoming space—she’s dubbed it a “public living room”—boasting healthy international snacks and local art. There’s always music playing, and sometimes her neighbours even come over to her stall for a little dance, she says.

The way she conceptualised and built the space was, naturally, influenced by her work in sociology and UX.

She’s long held a deep admiration for small businesses. They were a focal point of her post-graduate studies, and the highlights of all her overseas travels. She shows off a photo of a market in Uzbekistan that she shot.

“I love going to the market. There is so much creativity, energy, and camaraderie. And the vendors are so closely tuned into what people need, isn’t this human-centricity at its heart?”

The root of her love for market stalls lies in their propensity to help people access social mobility, she explains: “No matter your background, no one’s going to judge you. What your resume looks like, where you worked before this—it all doesn’t matter.”

I get the feeling that she could wax lyrical all day on the topic. You can take a sociologist out of sociology, but you can’t take sociology out of a market.

Wet markets, in particular, are the perfect incubator for small businesses due to the low stakes—there’s no lease, just a monthly rent—and high degree of freedom in shaping your business into whatever you want it to be, she adds.

Sadly, smaller wet markets have been squeezed by rising costs and competition from supermarkets, Leader of the Opposition Pritam Singh recently mentioned in Parliament. He’s also questioned the government’s long-term plans to preserve Singapore’s wet markets.

Honestly, what can they do? The reality is that young people these days rarely share Nazish’s fondness for wet market stalls. But that’s something she’s hoping to change.

“I also find that these shops are like masterpieces—the way they’re designed and arranged in this seeming cacophony. It’s actually very, very deliberate and intentional. It’s in conversation with people around.”

As a UX researcher, she began her shopkeeper journey with persona mapping. Who are the people coming to this market? What do they need that isn’t already being sold?

There were already stalls selling fruits, vegetables, coffee and provisions, she noted, but none selling healthy and affordable snacks. She started small, by bringing in some international snacks, and slowly built up an inventory through months of iteration.

Roasted chickpeas, muruku, and mushroom chips were winners with her crowd. Oats, not so much.

Besides her own work experience, Nazish also drew on the advice her fellow stallholders offered up.

“They told me not to overdo the interior, because a lot of people do that, and then they’re stuck with it. Do little by little, they said. That’s like, the agile way. That’s lean methodology.”

To this day, she hasn’t bothered to spend money installing a ceiling or wall fan, opting instead for a standing fan.

“These people could teach an MBA class,” she marvels. “That’s why I love small business. Why talk to Mark Zuckerberg? Talk to them, right?”

Little Joys

Nazish is upfront about being unsure how long she’ll keep Global Village Snack Shop running. But the 11 months she’s spent as her own boss have already been full of highlights.

She’s built a strong friendship with Ah Xin (who runs the provision shop next to her), Ah Guan, (who sells coffee), and Ah Hong and Ah Hue (sisters who have been selling vegetables at the market since 1969).

Most of her favourite milestones aren’t profit-related, she tells me. Rather, they all revolve around the connections she has built: the first time a customer returned to make another purchase, the time a customer asked her how to use chia seeds, the times when customers take a break on her stall’s stool and linger for a chat.

Where else do we speak so freely with strangers, trading recipes and stories?

“This is how information gets transmitted over generations. Because information is not always shared within the family. But as a society, this information is being shared through these neural networks,” Nazish says.

“When Ah Xin’s customer asked me about making chia seed pudding, I felt so grand! It’s the fact that she trusted me enough to ask for advice.”

While Nazish already knew all this in theory, getting to experience it firsthand as a shopkeeper was a different feeling.

“Who knows what I do with this experience? Am I going to work in policy one day? Will I return to tech?? I don’t know, but at least I understand the emotional satisfaction and challenges of a small business owner.”

An Experiment in Uncertainty

Global Village Snack Shop may or may not be a permanent fixture at Holland Village, but that’s beside the point. Its significance lies not in longevity but in the community it fosters.

It’s brought artisans, entrepreneurs, researchers, educators, and artists to the aging Holland Village Market. And, even as a lifelong Holland Village resident, Nazish now feels much closer to the community here, she tells me.

Nazish shatters the myth that knowledge is only found in academia; instead, she reveals that the richest lessons often spring from the overlooked corners of life—like our very own neighbourhood markets.

Choosing uncertainty over the comfort of stability? It’s the very foundation of striking it out on your own. It’s gut-wrenching—even more so if things eventually fall apart.

But the truth is, the most meaningful journeys don’t start with guarantees. They start with the raw, vulnerable act of simply stepping forward, even when the path is unclear.

As for what comes next, Nazish doesn’t have the answer. Perhaps she doesn’t need to have one.

“I don’t know when this will end or where it’s headed,” she says, with a spark of quiet defiance.

“But if you let the fear of failure control you, you’ll never do anything.”