All images by Nicholas Chang for RICE Media.

Last Sunday, a room full of people filed into Common Ground Civic Centre to talk about mental health. As these events usually go, there was a Member of Parliament in attendance—this time it was Dr Wan Rizal—mental health professionals, an audience of eager learners, and free food.

The event, Pretty Mental, was jointly organised by marketing agency The Black Sampan and Eagles Mediation & Counselling Centre (EMCC). The aim: reclaim the narrative around mental health and break down stereotypes.

ADVERTISEMENT

In conjunction with the event, EMCC also launched its It’s Not You campaign to remind us that we’re more than our mental health struggles. Stress, trauma and depression are personified into Inside Out-esque characters Stressia, Tarama, and Ah Dee. EMCC also has quizzes and toolkits on how to deal with these ‘characters’.

“We’re not trying to trivialise the conditions, but in normalising something, I think you need to make it appealing,” Elaine Tan, the executive director of EMCC, tells RICE.

“This isn’t just another talk,” The Black Sampan declared on Instagram. “It’s about understanding what mental health truly means, supporting each other, and embracing that it’s okay not to be okay.”

The message is familiar. Ever since mental health became a talking point in the national agenda, we’ve heard it across countless talks, panels, and workshops—in the past week alone, I’ve attended two. And they were both incredibly inspirational and essential.

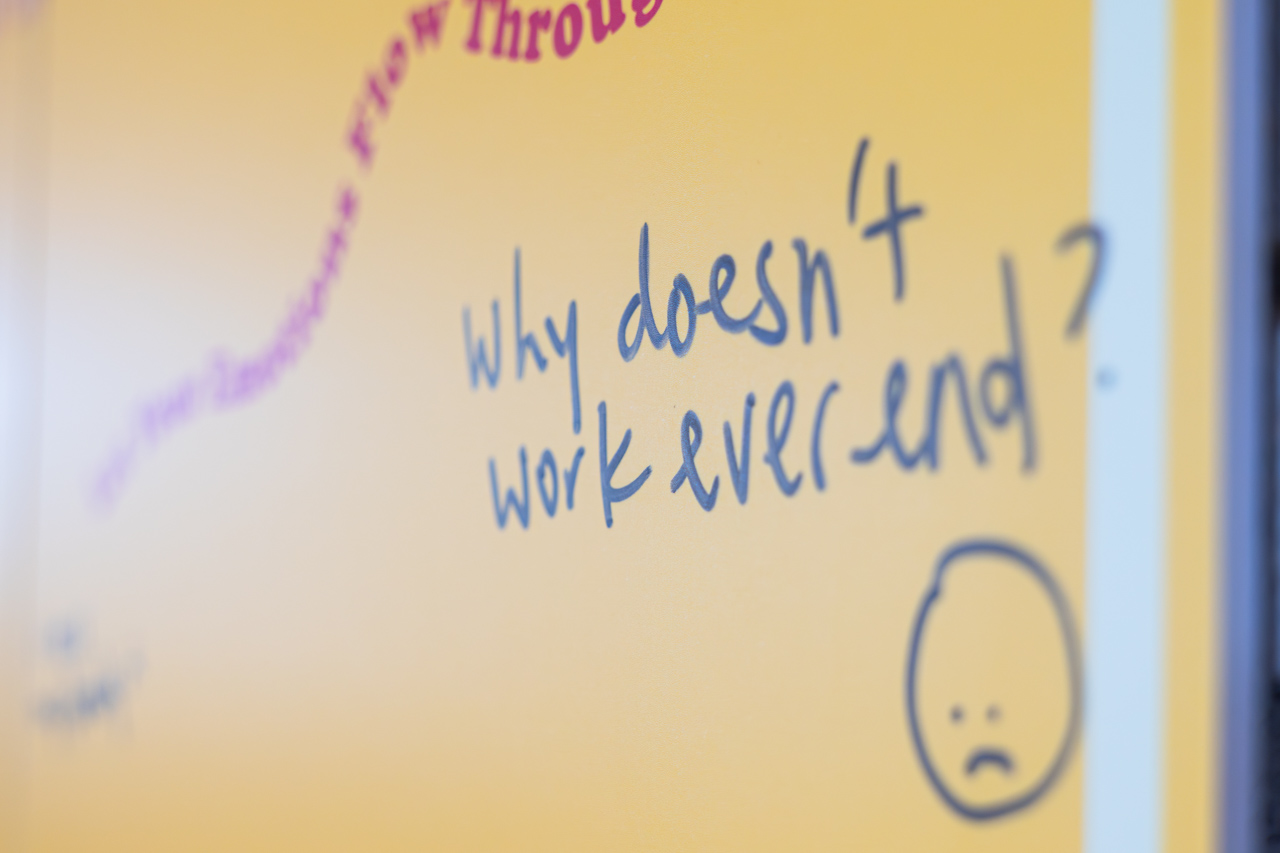

But at a certain point, I’m starting to wonder if we’re just preaching to the choir.

The people attending these events clearly care. But what about those who don’t? And more importantly, how does caring translate into real, tangible change? Did I really help anyone by spending three hours at another mental health event?

As the national conversation on mental health continues to grow, I can’t help but wonder if the true challenge is in moving from conversation to genuine action.

Laying the groundwork

That’s not to say the conversation bit isn’t important. Because it absolutely is.

ADVERTISEMENT

Awareness of mental health issues has improved, and mental health labels are “no longer dirty words”, TODAY reported in 2023. Still, we aren’t in a post-stigma world just yet.

Even as awareness has increased, mental health literacy is still a pressing concern. We’ve got some older folks who still think the first level of intervention should be an exorcism, as panellist Dr Wan Rizal mentioned.

“It doesn’t just stop at the Malay community. Other communities do have similar beliefs,” he added.

But what should we do if these older, more conservative folks aren’t educating themselves on the topic?

Fellow panellist Dr Jonathan Kuek, a mental health researcher, offers the perspective that more unfiltered conversations are needed to reach enough people for a cultural shift in society to happen.

“We need to become more comfortable with having uncomfortable discussions. And this will include, you know, having conversations where we actually use words that are potentially discriminatory and potentially stigmatising,” he says.

“And if I was to get offended, I will be shutting down the conversation. But I find it more productive to actually try and understand where they’re coming from.”

He raised the example of his parents, who didn’t understand why he’d choose to work in the mental health field. But they eventually came around and even offered to drive him to the Institute of Mental Health for his work.

That said, the frank discussion also revealed plenty of issues that panellists didn’t have easy solutions for.

Shiao-Yin Kuik, the executive director of Common Ground Consultancy & Civic Centre, offered a perspicuous take on how workplaces approach mental health.

“A lot of organisations are more prepared to say they’ll fund your little mental well-being day off and all these very individual level things, but much less likely to take a look at the larger policies and process that lead to, say, ‘X’ percentage of people quitting every year.”

Separately, several audience members highlighted their concerns over the shortage of counsellors in schools. Most schools only have one or two counsellors. And when counsellors are stretched, they only have the bandwidth to address students with the most severe mental health issues, they said.

To that, Dr Wan pointed out that there isn’t a quick fix as the field is highly specialised.

“If you think again, we are at a point where everything not enough, you know?” he added, referring to the shortage of social workers and other essential helping professions.

“Why is there shortage? As a country, we don’t have enough young people out there,” Dr Wan mentioned, pointing to our abysmal total fertility rate. And god knows the government has been trying so very hard to fix it.

Turning Awareness into Action

Throughout the panel, the phrase “move the needle” popped up repeatedly. Understandably, change comes in small increments—and it takes time.

But will the groundwork laid by groups like EMCC and The Black Sampan, as well as the government, right now lead to any real change? And how do we know that government initiatives like Singapore’s National Mental Health and Well-being Strategy are on the right track?

Truthfully, no one has the answers. But it’s promising that we now hold space for open discussions about gaps in the system and all the areas that need changing.

What’s often missing in the conversations so far, however, are hard targets, deadlines and commitments.

When I ask Dr Wan about this, he candidly admits that he too, is a numbers guy. But measuring progress is not a simple matter.

“As a data scientist, you want to see changes in terms of quantity—quantifiable numbers. But at the same time, this is not a quantifiable issue. It’s actually very much a qualitative issue,” he explains.

“And a qualitative issue means that it needs a different kind of approach. It’s not just about numbers. It’s about understanding the ground.”

It’s events like Pretty Mental, as well as grassroots events and focus groups, that help him get a sense of on-the-ground sentiments.

That said, the government is in the process of formulating a set of Key Performance Indicators (KPI) that will be able to indicate if it is moving in the right direction, says Dr Wan.

While he doesn’t share any specifics, he gives the example of qualitative indicators such as the number of acute psychiatric beds in facilities. He adds that we also need a balance of quantifiable and qualitative KPIs.

While Dr Kuek is optimistic about the government’s National Mental Health and Well-being Strategy, he says his line of work as a researcher can sometimes be disillusioning.

Sometimes, it’s discouraging when it feels like the findings for the work he does aren’t being implemented, he tells me.

For example, he’s been pushing for more campaigns led by people with lived experiences. This is one area that is lacking despite awareness campaigns such as Beyond The Label, he says.

“In relation to advocacy work, when they don’t actually have the power to enact changes, then you end up with a much more standardised and equally valid, but still less raw representation of mental health issues,” Dr Kuek explains.

“Sometimes you get responses. Sometimes they don’t really respond to you, and that’s just part of the cause of being an advocate who speaks a bit different of a tune, as opposed to someone who is just out there talking about awareness.”

What Next?

We’ve been told time and again by numerous public education campaigns that it’s okay to not be okay.

But what comes next? Will we see concrete changes in our schools and workplaces to ensure that mental health support goes beyond words? Will policies shift to guarantee real, lasting solutions, or are we stuck in a cycle of awareness without action?

Stigma may lessen, but it will likely never go away, Dr Kuek tells me. It’s like sexism and racism—you can change policies, but if attitudes can’t shift, people simply become better at hiding their discrimination.

Dismantling stigma is important, but equally important is allocating resources to identify and plug the other gaps in the system.

It’s clear that mental health is yet another social issue the government can’t tackle alone. Real change will take time, but without collective action, progress will stall.

Dr Wan puts it this way: “The government can get everybody to sit in a room together, but if they don’t want to talk or shake hands, it’s also a problem.”

“But what the government can do is provide direction. And the fact that they already mentioned that it’s a national priority, I think that’s a big start.”