Header image: Taylor Swift/Facebook.

The past few weeks have been tough on fans of Coldplay and Taylor Swift.

From queuing outside Singpost outlets overnight and applying for UOB credit cards, to having multiple tabs, and multiple screens, with the Ticketmaster website on standby, it’s a phenomenally stressful time for them. It’s clear nothing, not even an additional three dates, can soothe demand for tickets.

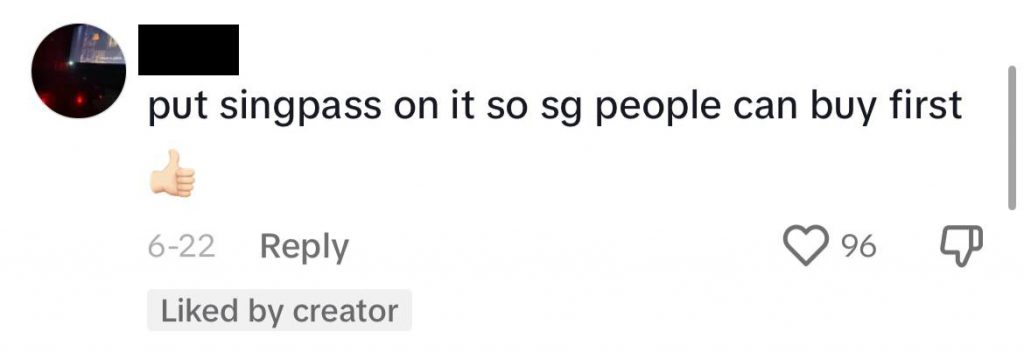

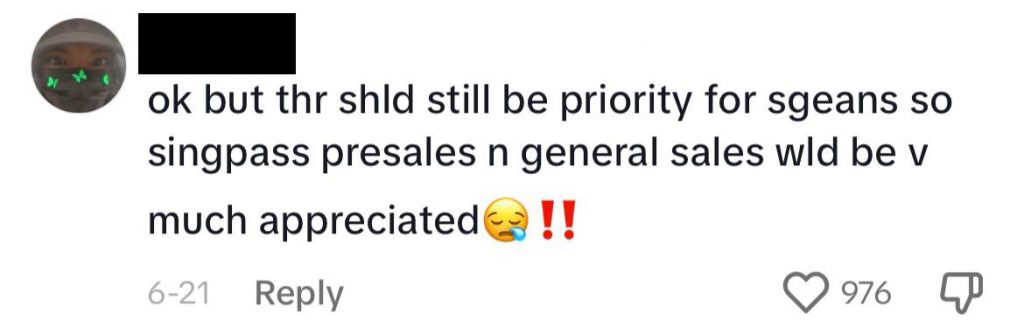

But the concert fever has yielded yet another strange phenomenon: numerous requests, in the form of TikTok comments, demanding the government reserve Taylor Swift tickets–for her only tour stop in Southeast Asia, no less– for Singaporeans.

Preferably by NRIC number or, even more conveniently, Singpass.

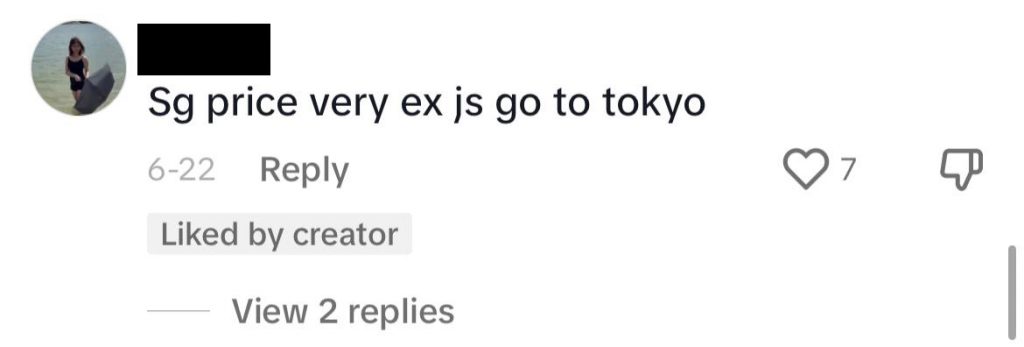

Cue the (mostly in jest) arguments on Twitter and in TikTok comments sections: Singaporeans assuring their Southeast Asian counterparts that the National Stadium, which is a part of the Singapore Sports Hub, is really not great. Wouldn’t it be more fun to go to Japan instead? Haha.

You’d think we were still in the early days of the pandemic when nations were seizing all masks and vaccines within their countries’ borders. Difference being no one ever died from not seeing a Taylor Swift concert (though some of my friends would disagree).

It’s not surprising Swifties went online with their grouses. Complaining on social media has become kind of a modus operandi if you want things to get done in Singapore. But with much of ‘complain culture’ here, it might not lead to any actual change.

Especially when they run up against large government projects–with the political will, and dollars, behind them.

The Economics of Priority

As some eagle-eyed Swifties have noted, the Singapore Tourism Board logo has appeared on its promotional posters. Taylor Swift and Coldplay are just some of the acts that have been courted to Singapore as part of a larger, long-term tourism strategy to make Singapore a top entertainment destination.

Hosting big-name events–like the Olympics, Formula 1 races and pop star concerts–is big business which countries engage in out-and-out bidding wars over.

And the effort to secure these acts–which, according to The Business Times, involved “a broad spectrum of key industry players […] including event organisers, sponsors, and partners”–is suggested to have only been made possible by the financial commitments of the Singapore government.

In fact, considering the headline-grabbing angle of Singapore as Swift’s only Southeast Asian stop, it wouldn’t be a reach to guess that securing a large number of concert dates–which could have gone to other Southeast Asian cities instead–was part of the deal to rake in the tourist dollars.

So, sorry Swifties. This is the reason why all of Taylor Swift’s Southeast Asian fans are fighting with you for tickets. But it may also be the reason why she is even performing here in the first place.

Is All of This Fair?

To me, the calls by local fans for the government to gatekeep Taylor Swift tickets by Singpass are eerily reminiscent of a hot-button talking point: the ‘reserved for Singaporeans’ framing seen in common political rhetoric that becomes a slippery slope into xenophobia.

It seems many Singaporeans have been habituated into more than just reflexively calling for the government to intervene whenever an issue arises.

We are also used to seeing the solution as, simply, reserving privilege for Singaporeans.

Yet, I would be hesitant to reduce such sentiments to xenophobia or even the stereotype of the ‘entitled Singaporean’.

In a sleek TikTok interview clip-cum-promotional video by Mothership, current Minister for Culture, Community, and Youth (MCCY) Edwin Tong replied to the question of whether Taylor Swift tickets could–or should–be restricted by Singpass.

As he put it, “We need to make sure it’s fair, that when Taylor performs here, we will have access to all, not just Singaporeans.” That’s a no.

But is reserving some tickets for local audiences necessarily ‘unfair’?

As some Singaporean fans have pointed out, Taylor Swift fans living in Japan are relatively more sheltered from ticketing wars as compared to Singaporeans. Over there, concert tickets are mostly purchased locally or require a Japanese SIM card, naturally putting up some barriers to entry for foreigners.

What kind of accessibility is there when a business aims to maximise profits? Is access to the highest bidder really what the average person sees as access?

In a discussion of whether Singapore should introduce anti-scalping laws in a TODAY article, SUSS professor Walter Theseira notes: “From the economics point of view, one reliable measure of how much of a fan somebody is, is how much they are willing to pay.”

I know many Swifties who would disagree with that definition of a ‘fan’.

If we truly want concert tickets to be accessible–meaning, the average fan still has a chance at a ticket–access cannot be left up to the free market. If the main objective is profit, however, that is a different story.

If Singaporeans reflexively call for benefits to be locked behind the paywall of citizenship, this is because the framework of “benefits of citizenship” is the solution that has been presented to us time and time again.

We are surrounded by this model in almost all realms of life: from healthcare subsidies determined by citizenship tier, to an education system where citizenship status is used to select between students with the same PSLE score for admittance to schools.

Benefits of Citizenship? (No, Not NS)

In the same TODAY article, NUS professor Lawrence Loh argues that government intervention usually addresses issues with social objectives.

“For example, if it’s housing, then you have to control the number of foreigners, add stamp duties,” he says. “These are just entertainment events that are discretionary.”

But aren’t entertainment events culturally and socially important to people too?

The assurances, that Taylor Swift concerts here will rake in big tourist dollars that will benefit our economy, may be scarce relief for those who consider seeing her as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

Similarly, the oft-trotted belief, that certain policies or undertakings are necessary for Singapore’s future-slash-economic growth-slash-reserves, may not really matter to Singaporeans who feel that housing and retirement are now out of reach for them.

Which is why I don’t think it’s useful to simply brush off calls for tickets to be reserved via Singpass as selfish fan behaviour. Just like it isn’t productive to reduce all grievances around citizenship as “populist” or “xenophobic”.

Does the average fan who feels robbed of their chance of seeing their idol live–or the average Singaporean–actually feel like they benefit from the government’s effort to make Singapore a global concert venue and top entertainment destination?

Behind the sometimes-toxic rhetoric, many Singaporeans have legitimate concerns: for one, over whether we are prioritising some forms of economic growth over the quality of life of those who live and work here.

And in a time when many are feeling increasingly precarious, is it any surprise that Taylor Swift fans grasped onto citizenship when let loose in a sea of intense global competition?

What Do Swifties Want?

Luckily, Swifties here have surprised me.

My fear was that the rabid calls for Singpass-priority tickets sales would devolve into yet another display of the ‘ugly’ Singaporean on social media. But I haven’t seen any conversations between Singaporeans and other Southeast Asian fans get nasty… yet.

There’s a difference between wanting tickets to be accessible to local fans, and demanding all Singaporean (citizen and PR) ticket buyers to be prioritised over all foreign ticket buyers. And while I’d like to think most fans care about fairness, I’ve seen others call for the latter.

The nationalist undertones of this conversation are a reminder that–despite the temptation to tell ourselves that younger generations will bring about social or political change–we cannot brush off xenophobic sentiments as a thing of the past. Not when it still lurks in the present.

All things considered, I don’t see it going anywhere. Not until we address the question of whether Singaporeans feel they reap the benefits of living in Singapore. And, in Taylor’s version, whether they’re being left out of the fun, or if they’re happy having it outside the Sports Hub walls.