All Images: Laili Abdeen for Rice Media

As soon as my colleague, Yulianna, and I stepped into the therapeutic garden, the cacophony of raucous laughter amongst picnic-goers outside dissipated into the air. Standing at the entrance on a Sunday afternoon, we watched as families and youths strolled past, oblivious to the little enclosure camouflaged by a wall of trees.

Inside, our only company was the motley of butterflies as the occasional child traced their flight path with tiny, chubby fingers.

Singapore’s largest therapeutic garden is as immersive as it is inclusive—its amenities, dedicated to behavioural and emotional needs, are an enormous milestone for the country. Between focusing on navigating around twists and turns as well as the quietude of the place, you can’t help but be fully engaged and captivated inside Jurong Lake Gardens’ newest attraction.

Still, this was not the first inclusive garden or playground in Singapore. In fact, with ten playgrounds sporting wheelchair-accessible swings, merry-go-rounds, and sensory play gardens, the question plaguing my mind was what exactly sets this particular garden apart from the rest.

Mythical forest

I looked around, enraptured by the sheer greenery of the space. With a ring of trees fencing it, stepping into the garden feels like stepping into the MCU’s mythical Ta-Lo from Shang-Chi.

Much like its elusive cinematic counterpart, the therapeutic garden also evades the eyes of fitspo joggers and bike enthusiasts on the tracks right outside. Most park-goers flock to the open space across the therapeutic garden, opting for picnics and playing frisbee with friends.

With no CGI fight scenes here, the garden’s stillness is a drastic change from the clamour of MRT stations and hawker centres.

Sofia*—a friend working in a local special needs school—explained how it is likely that regular playgrounds can be too overwhelming and overstimulating for some special needs kids. The needs of neurodivergent children are not always understood by neurotypical adults and peers, commonly being perceived as ‘naughty’ instead.

Children with special needs are likely to be free of judgement in this ethereal mini-forest. Apart from the beady eyes of ants, the quiet rustling of leaves here escapes most of the stares, or glares, of others. People barely noticed Yulianna and I roaming around, only making a mental note to avert our gaze once they realised we were looking for people to interview for this article.

The garden’s seclusion definitely gave it the tranquillity necessary for children with behavioural needs. The butterflies sailing through the foliage, perched on the tips’ serrated leaves, exude the serenity needed for these children that most Singaporeans may be overlooking, myself included.

For most of us, the place feels like just another Instagram worthy snapshot along our jogging routes, but for kids with special needs, it may be the solace they sought but could not find in interactions with neurotypical children.

Enchanting nothingness

With the growing awareness in the Singaporean community about persons with disabilities (PWD)—from our commendable performance in the Tokyo 2020 Paralympics and to equipping our teachers with the necessary skills to support students with different learning abilities—it’s no secret that Singapore is looking into creating a more inclusive landscape.

The gardens’ lush flora transforms inclusivity into a mythical island a la Peter Pan’s Neverland. The silver xylophones, effortlessly rung by the occasional visitors, lull you through your worries, symphonic melodies reverberating through the foliage. With pathways snaking over little mounds and around swings and slides, it’s easy to feel like a little Dora the Explorer.

Our favourite spot was the homage to the pandan leaves, kang kong, and tamarinds freshly plucked in kampong days of yore. The scent of these spices and herbs glides into an image of the classic Asam Boi drink and Kuih Dadar, both conveniently included in a wooden recipe book on display.

It’s been a month since the initial announcement, and perhaps the hype has died down—an understandable phenomenon in a country that tends to ebb from one trendy landmark to another. Or maybe the Sunday we chose was far too scorching for parents to want to bring their kids out for a walk through the park.

Still, particularly jarring, was the absence of the very demographic the garden is supposedly tailored for.

A maze within a maze

The selling point of the garden is its inclusivity as well as how therapeutic it can be. Safe to say, it is bound to deliver the latter considering the serene and sensory experience of traipsing through various thematic zones engaging one’s hearing, sight, smell, and touch. Topped with a Butterfly Maze, the garden provides a plethora of options to stimulate the senses while calming the nerves simultaneously.

However, what seems to be a point of concern is its accessibility for people who live nowhere near the West, should there be families with special needs children residing beyond Jurong.

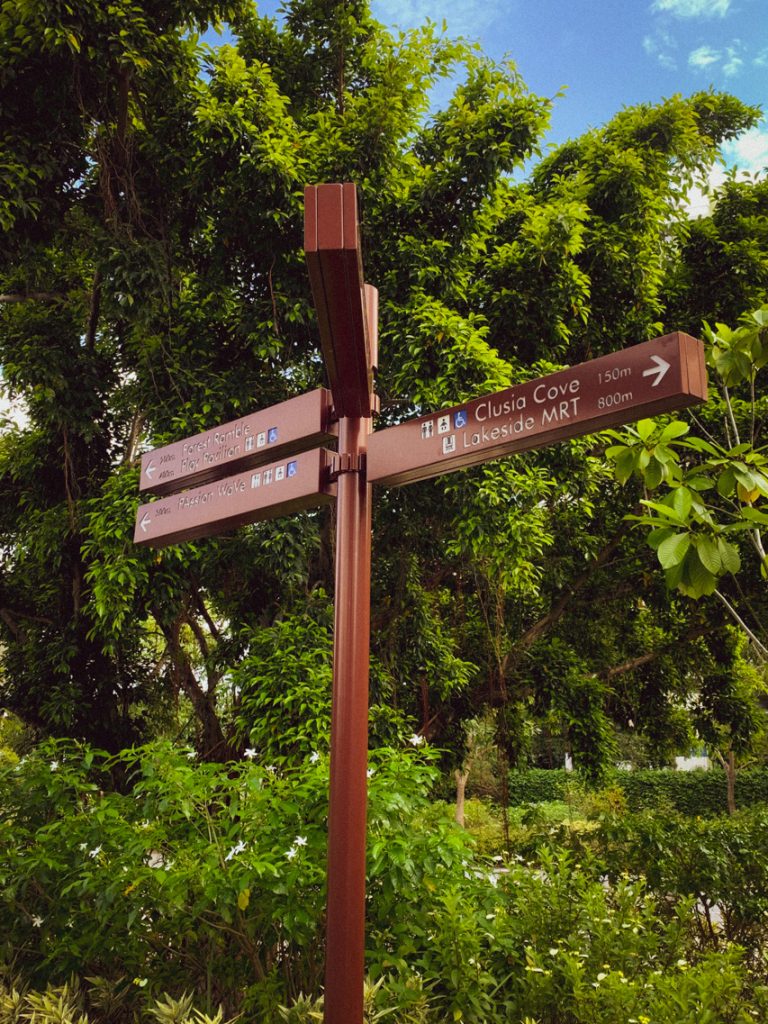

If you live in the vicinity, the garden is a 10-minute hike from the entrance pavilion, which may feel inconvenient or troublesome for some. Even from the nearest MRT Station at Lakeside, one must first weave through the labyrinth of the enormous national garden, past a fusion food court and lalang field, before arriving there, after about a good fifteen-minute walk.

The garden is undeniably a landmark to be lauded with amenities dedicated to the special needs of children. Yet its very design, which transports an individual to a Wonderlandeqsue environment, may also be a reason for its relatively barren state.

Lost opportunities

Besides play areas, schools tend to be the go-to platform for social interactions to blossom. We tend to recall P5 adventure camps or unreasonably strict CCA teachers as lived experiences that we can bond over.

So it feels tempting to jump into a snide commentary about how the garden felt like a microcosm of education in Singapore, where behavioural needs feel like an afterthought in a system geared towards abled students. Or how the park appears to sequester neurodivergent children into spaces that don’t disrupt the fabric of Singaporean society, much like special needs schools.

But all these claims stem from the same presumption: the end goal for ‘inclusion’ as we know it to be the gradual integration of special needs students into mainstream schools.

It’s easy to fall into this trap of elevating our mainstream schools on a pedestal, no matter our grievances about tuition fees and difficult PSLE math questions.

Rote learning methods, though pedantic, have produced countless students who continue to thrive as they study and work through a pandemic. Our full-time university enrollment stands at about 76 thousand in 2020 alone.

“On the other hand, our schools have a more functional slant. We focus on equipping our students with independence over results,” shares Sofia*, who teaches in a local special needs school.

Their school focuses on goals that transcend literacy and numeracy, looking at skills centred on daily living and social-emotional learning. An epiphany crossed my mind as she described how they teach skills ranging from counting money to cooking.

Perhaps another way to look at inclusion for students with special needs was not by assimilating them. Instead, we could start looking at what we can learn from an alternative form of education.

Walk to remember

As able-minded parents and students, we may succumb to thinking that our current educational pathway, though fraught with stress, is the only means to attaining the ‘Singaporean dream’ of the five Cs.

“I used to think the same way, too,” says Sofia, who has been working as a learning facilitator for a year. “Like ‘why can’t they all just join mainstream schools?’ But working here has shown me a different side to education.”

With personalised goals and a customised learning roadmap for each student, their programmes are tailored to appeal to the needs and abilities of each student.

I imagined a utopia for education, where each student is granted the freedom to explore their vocational strengths, hone and develop them or even change their minds later. It seems idealistic but likely no more surreal than the enchanting gardens we eventually walked out of.

It seems that the therapeutic garden was, in fact, a symbol—a reminder that Singapore is capable of holding space for people from all walks of life should we set our minds to it. It is proof that a country can make tangible change and progress in the right direction once we start making it our priority, as we have now done for special needs.

Undoubtedly, both mainstream and special needs schools bring their own set of merits to the table. Similarly, there are perks of placing this garden in the quiet embrace of our Western winds. However, in the faint whistling of the trees, what continues to plague my mind is:

What interactions, values and learning styles do we lose by separating these two forms of education?

*Name has been changed as learning facilitators are unauthorised to speak to the press