Top image: Sean Lim/RICE

In the “Singapore Parliament Unpacked” series, we unravel some of the less-commonly known apparatuses of our nation’s law-making body.

In the first of a series, our writer delves into the official parliamentary records, also known as the Hansard, which has been recording every word uttered in the chamber since 1955.

Don’t judge a book by its cover, as the saying goes.

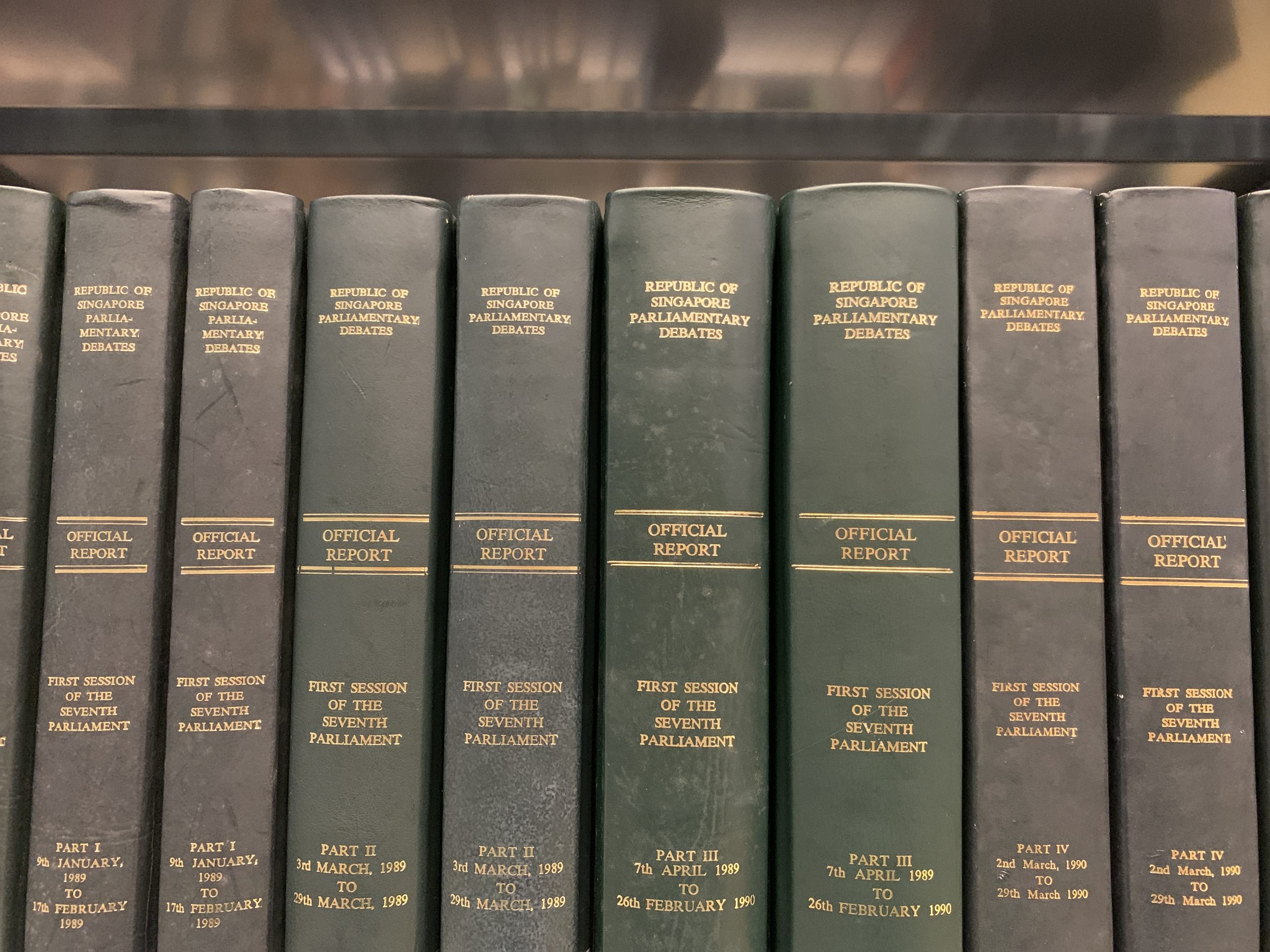

The nondescript covers and chunky volumes of the official parliamentary records, also known as the Hansard, may look dull. But they throw up interesting nuggets about our six decades-old legislature if you bother to dig through the documents.

For instance, did you know the People’s Action Party government was almost overthrown in the early 1960s—not once, but thrice?

Or the time in April 1963 when former Barisan Sosialis leader Lee Siew Choh gave a marathon speech of more than six hours when MPs were debating whether to arrest left-wing extremists by the Internal Security Council, starting at 11.19 PM and ending at 5.48 AM the next morning.

How Hansard works

But entertaining titbits aside, having parliamentary proceedings on record is an important part of democracy to ensure accountability and transparency.

Since the first sitting on April 22, 1955, every word uttered in the hallowed halls of Parliament is recorded in the Hansard, named after the family whose firm originally published the official records in UK’s Parliament. This also includes Parliament’s Select Committee meetings.

Whatever MPs say in the House must stand up to scrutiny because any changes in positions, factual errors, or poor arguments made can be traced back to them. The Hansard, in no small part, plays an important role in ensuring the immunity accorded to MPs is not squandered or misused.

When MPs gather in Parliament to debate issues of the day, a team of note-takers, seated at their workstations away from the chamber, will transcribe the debates in full, with the help of video recordings and machine-transcription software.

In the past, they had to be in the chamber and scribble in Pitman’s shorthand on a notepad, with the help of a tape recorder, and then head back to their desks to type out their notes on typewriters.

For MPs who speak in either Mandarin, Malay, or Tamil, their speeches will be simultaneously interpreted into English by interpreters, who are seated in small rooms with windows overlooking the chamber. The rooms are located behind the Speaker’s gallery, where currently, MPs such as Poh Li San, Dennis Tan, and Hany Soh are seated.

These note-takers will jot down notes based on the English interpretations, with the MPs’ original non-English speeches included in the Hansard later on, during publication.

These note-takers are also called verbatim reporters as they will jot down everything, word for word, except for expletives. Expletives are generally not recorded in the reports because unparliamentary language is not allowed in the debates, save for an incident in 1995 when the MP had to apologise for it (see Ling How Doong’s “talking cock” comment in the later section of this article).

Depending on how busy Parliament is, the length of the day’s sitting, and the number of sittings, the Official Reports Department will then decide on the number of transcribers and editors to deploy.

Documenting every cut and thrust of what goes on in Parliament is a specialised skill. To be qualified as a verbatim reporter, one has to undergo training, which consists of on-the-job practice and attending parliamentary reporting courses and conferences organised by other Commonwealth parliaments.

They also have to be constantly kept up to date with new reporting software and IT skills. For the editors, they are part of the UK-based Commonwealth Hansard Editors Association.

Post-sitting

After a parliament session ends, the Official Reports Department will email the first draft of the recorded proceedings to MPs for them to verify that whatever has been spoken is accurate. If there’s an error in the text, MPs have to write to the chief reporter and editor within 72 hours.

MPs can only request minor edits to remove typographical and grammatical errors or to smoothen out sentences, but not factual corrections. If MPs want to change the substance of the speeches made, they must inform the Speaker, who will make the final call.

After everything has been verified, the official records of the debates will then be published on Parliament’s website. The whole process, from the adjournment of a sitting to publication, takes at most seven working days.

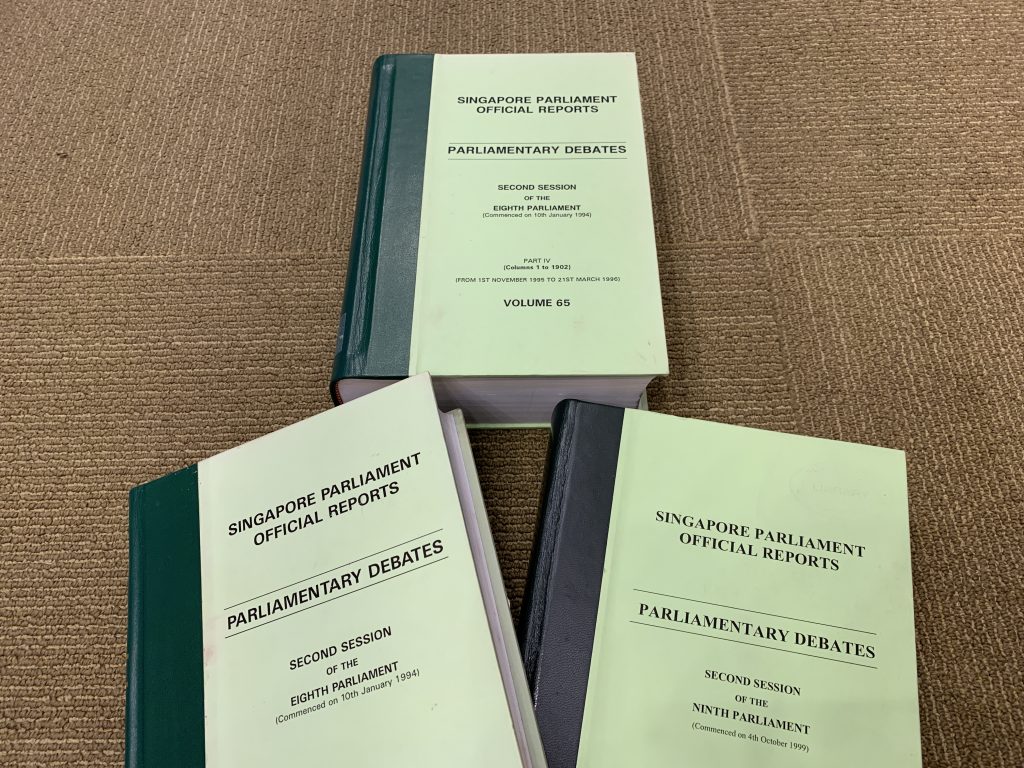

Of course, these days you don’t have to manually thumb through those thick physical volumes of Hansard at the National Library, which contains about 15 parliamentary sittings per volume. Those are bound and printed by Toppan Leefung, formerly known as the Singapore Government Printing Office.

Since 2000, the Hansard has been available publicly online, with documents indexed neatly in various categories.

Hansard ramifications

For a concerned Singaporean keen to know how active their MP is and whether their concerns are raised in Parliament, the Hansard is a platform to gauge their performances. This is more accurate than relying on news outlets with limited bandwidths and column inches to cover everything in the House.

Hansard was where I found out that my own MP from the previous term, Ong Teng Koon, spoke on nine Bills and asked 45 questions from January 2016 until end-2019.

On the other hand, Louis Ng of Nee Soon GRC spoke on 131 Bills and filed 235 parliamentary questions in the same period.

Numbers aside, Singaporeans can also use the Hansard to judge if their representatives had spoken with substance, backed with logical ideas and probing questions, or given speeches filled with motherhood statements and polysyllabic buzzwords that didn’t value-add the debate.

There have also been instances where the Hansard was used to hold politicians to account for what they said and the stand they took since every word uttered was recorded. Citizens can refer to the records and check if MPs delivered their election pledges and spoke on issues they said they would.

Even MPs themselves had used the Hansard against their political opponents during debates, especially when they discovered a change in position on a subject. When faced with such cases, politicians on the receiving end would have to explain themselves.

Just last month when Parliament debated over the Foreign Interference (Countermeasures) Bill, or FICA, Leader of the Opposition Pritam Singh quoted a 1989 speech made by K Shamnugam during a debate to amend the Internal Security Act.

In that debate, Shanmugam, who was then a backbencher, advocated for more checks and balances, and was concerned over the limited judicial review in the amended legislation.

Now as Law and Home Affairs Minister, Shanmugam proposed to limit the role of the courts for FICA, which was the very thing he was concerned with three decades ago. The Workers’ Party seemed to have suggested that the minister was inconsistent.

In response, Shanumgam said: “A person who is prepared to be thinking about issues sometimes has to change his views when he is faced with the real world and experiences.”

Interesting nuggets as seen from Hansard

While our Parliament may not be as rambunctious or theatrical as the UK’s House of Commons, there were still memorable episodes that would have been tabloid fodder. These can be found from the Hansard if you bother to look it up.

Here are four examples:

Choo Wee Khiang “Little India” comment, 10 March 1992, during the Budget Debate

Choo Wee Khiang (MP for Jalan Besar GRC): (In Mandarin) One Sunday night, I went to attend a dinner function. I drove to Little India. There was complete darkness, not because there was no light, but because there were too many Indians around there. [Interruption].

No, I am not trying to play on communal lines. Sorry, we have Indian compatriots in this House. But I can tell you, the moment you open your eyes, you can see straight away that they are not Singaporean Indians. Because their behaviour and expression are different from the Singapore —

Chiam See Tong (Opposition MP, Potong Pasir): Point of order, Sir.

Speaker: Yes, Mr Chiam. What is it?

Chiam: Sir, I think the honourable Member —

Speaker: Are you raising a point of order?

Chiam: I am raising a point of order.

Speaker: What is your point of order?

Chiam: I think it is not proper for him to make fun of other races.

Speaker: Mr Chiam, that is not a point of order.

Chiam: He should not make fun of other races.

Speaker: That is not a point of order, Mr Chiam. You may continue, Mr Choo.

Choo: (In mandarin) Mr Chiam has once again misunderstood me. Last year, he misunderstood me. The year before, he also misunderstood me. He does not have enough sense of humour.

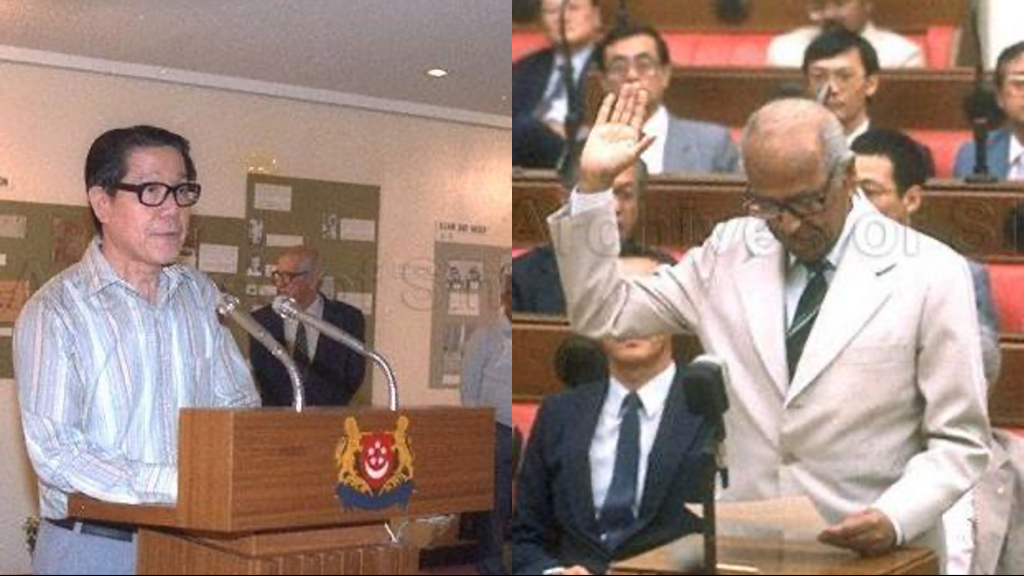

The Jek-Rajaratnam confrontation, 6 March 1985, at a debate on the President’s address.

Senior Minister S Rajaratnam: …He said that after his departure from Singapore and from his ministerial duties six years ago, he returned to find that during his absence things had gone to pot in Singapore.

Former cabinet minister and MP for Queenstown Jek Yeun Thong: I didn’t say that. On a point of clarification. I think the Minister is putting a lot of words into my mouth.

Raja: I am just repeating what I thought I heard. But he can –

Jek: He could be senile really.

Raja: Perhaps if the Minister will listen to me and he can deny that these are the things that he said.

Jek: I am not a Minister now.

Raja: I am glad he said it because I shall quote it —

Jek: So who is senile, then?

…

Raja: …After mentioning the sorry plight of the poor, quite correctly, he went on to contrast this with the six-fold increase in the pay of MPs and what he incorrectly claimed was a 10-fold increase in the pay of Ministers. In fact, it is only 6.7 per cent but it does not matter. What is a few per cent?

Jek: How much is a Minister paid now?

Raja: This is very interesting. Yesterday, he simulated he did not know how much he was getting. He turned around and asked, “How much is an MP’s pay?” You are an MP. You were a Minister.

Jek: But that was years ago.

Raja: Not many years, six years ago.

Jek: There is a vast difference.

Raja: Six years ago it was increased. Please do not try to prevent me speaking. Let me finish this thing first.

Jek: Is it so difficult to tell how much is the pay of a Minister now?

Raja: $17,000.

Jek: Well, I rest my case.

…

Raja: …I can understand the Member for Potong Pasir (Opposition MP Chiam See Tong) doing it because he had to get into this Chamber. He needed the politics of envy to help him win his election and I like to think that ministers’ pay helped him to get into this Parliament.

But what need was there for the Member for Queenstown who rode into this Chamber on the PAP horse to play the same game? What need was there? This is inferior politics. Now, it may be fun to shoot your faithful horse. But I think it is not a nice thing to do either to the horse or to the cause.

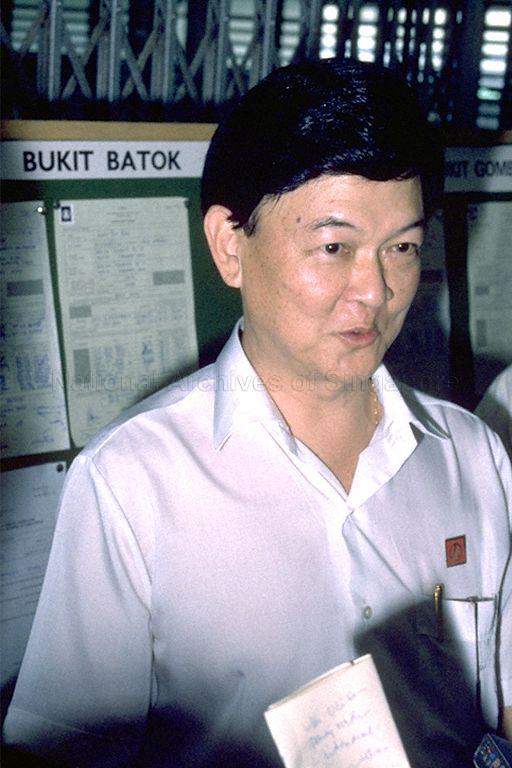

Ling How Doong’s “talking cock” comment, 3 November 1995, during a debate on the independence and integrity of Singapore’s judiciary

DPM Lee Hsien Loong: Is Mr Ling aware that Dr Chee is on record as claiming that this speech was written and settled before he left for Williams College?

Ling How Doong (Opposition MP for Bukit Gombak) : I suppose he said so. I am in no position to know. I do not know whether he prepared the speech —

An MP: What kind of chairman are you?

Ling: —before he left. I have no idea.

DPM Lee: Mr Speaker, Sir, I am afraid I took the SDP … [Interruptions].

Mr Ling How Doong: —talking cock—

Speaker: Order. Resume your seat, Mr Ling. I want to remind the Member that he should refrain from engaging in conversation in the House with others.

Ling: Mr Speaker, Sir, he was talking of funds. I am not going to tolerate a chap who does that. He should seek your permission first before he speaks to me. When he is unparliamentary, why should I be parliamentary to him? [Interruptions].

Speaker: I have not heard him.

Ling How Doong remained standing.

Speaker: Order in the House. Mr Ling, I have not heard any remarks being made. But I heard you engaging in a conversation with somebody else, and I think this is not the proper way to participate in a debate in the House. You will address the Chair and you will do so when you are asked to do so. Resume your seat, please.

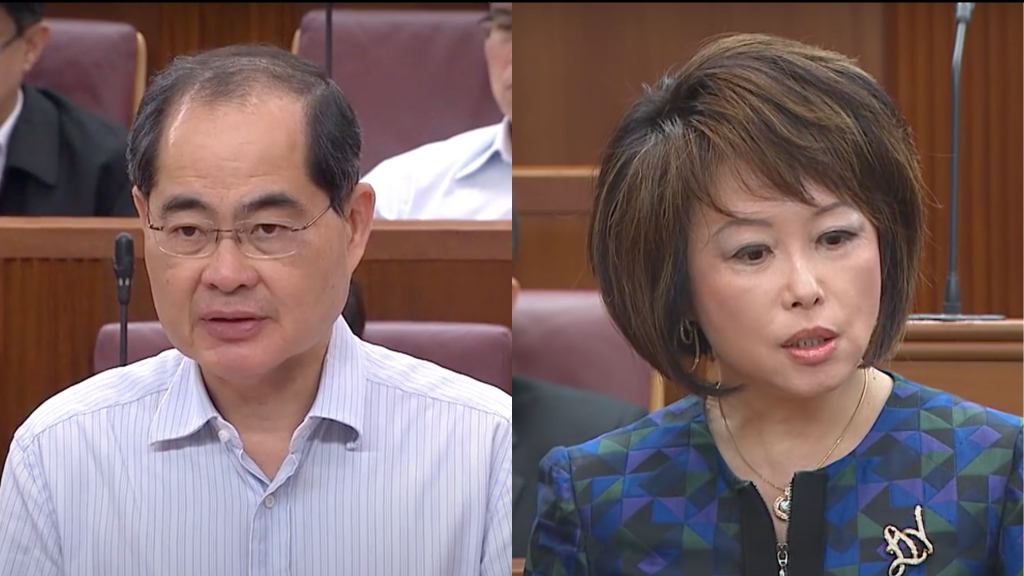

Lim Hng Kiang’s controversial “hairdo” comment, 13 August 2001, during Question Time

Dr Lily Neo (MP for Kreta Ayer-Kim Seng GRC): Sir, may I ask the Minister whether it is correct to say that mammography in the polyclinics is only applicable to women aged 50 years and above on demand, that there is no population screening programme and there is also a co-payment fee of $50 for each screening? But since an average of three women are diagnosed with breast cancer, half of them are below 50 years of age, and that breast cancer is curable if detected early, should not the Minister facilitate more women to go for early screening and save lives?

Mr Lim Hng Kiang (Minister for Health): We have to use our Medisave carefully. I sympathise entirely with women who want to do their breast screening early. I would urge them to do so. My usual reply to them is: save on one hairdo and use the money for breast screening. I have been taken to task by many of my hairdressers in Telok Blangah but I think this is still my main message.