If Singapore had a national ghost, it would not be the Pontianak. It would be the Kampung Spirit.

Hardly a week goes by without someone trying to bring it back from the dead. Every mainstream media outlet has a slew of hand-wringing articles either lamenting its absence or insisting upon its survival. There is a state-of-the-art apartment complex incongruously named ‘Kampung Admiralty’, and even an app that promotes ‘kampung-style sharing’.

Needless to say, it has not become the next Tinder or Grab.

But the worst offenders are our Mediums/Ministers, who cannot stop chanting ‘kampung spirit’ when called upon to discuss social issues. PM Lee wants us to revive the Kampung spirit by holding open lift doors while Minister Heng Swee Keat declares ‘It’s Alive!’ after seeing a community garden.

Lawrence Wong wants to build shared spaces to hasten its growth and let’s not forget Minister Khaw Boon Wan, who once proposed ‘kampung spirit’ as a substitute for functional trains.

Rather nauseatingly, even Google has gotten in on the act. Singapore director Joanna Flint, called the company’s offices a ‘kampung’ because she wanted to convey a ‘sense of community’.

The messengers vary, but the message never does. When someone invokes the kampung spirit, he’s basically moaning: Why can’t we help each other more often? Why can’t we be nicer people? Come on guys, where has our community spirit gone?

I can answer this question: the kampung spirit is not dead. It never existed in the first place.

To address the myth of Singapore’s kampung spirit (a.k.a gotong royong), we must first define it. Not an easy task because nobody knows what it means despite its near-ubiquitous presence in print.

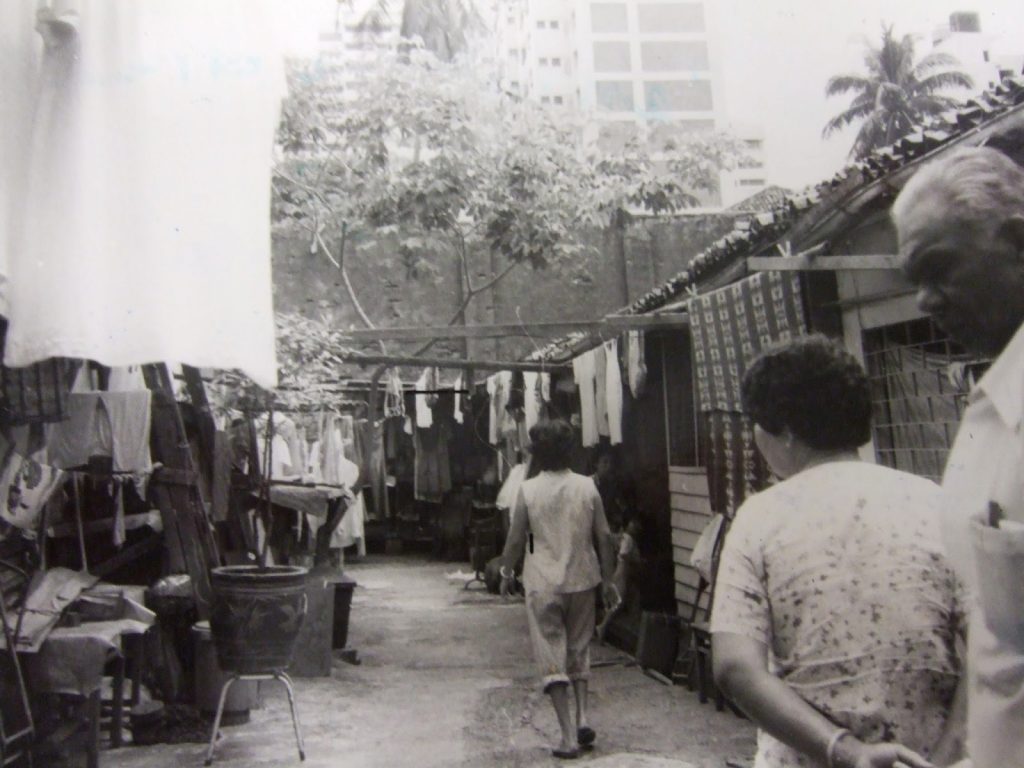

The generally-accepted meaning is camaraderie, community spirit, social cohesion, a willingness to help others, and above all, neighbourliness. It hearkens back to a golden age in our history when every door was open, our neighbours more neighbourly, and the average Singaporean a kinder, more generous soul.

Unfortunately, this mythical time exists only as nostalgic fantasy. Kampung living did not make us ‘better’ people. Not now, not then. It did not produce in Singaporeans some sort of innate goodness that was lost upon contact with electricity and running water.

Take for example, the oft-repeated claim that our kampung days had more ‘social cohesion’. By this, most commentators mean that neighbours were more sociable. They knew each other by name and talked cock on a regular basis.

What critics often forget are the reasons for this sociability: Chronic unemployment and a lack of amenities. In pre-independence, pre-modern Singapore, that was no such thing as a ‘career’. Most kampung dwellers worked what we now call ‘odd jobs’ in the informal economy, that is if they could find employment at all. Many men worked part-time on the docks while the women laboured as laundresses cum housewives.

As sociologist Chua Beng Huat describes it: ‘[The Case] for the overwhelming majority was one of unemployment or intermittent employment in terms of both working hours and number of days worked per week’.

It is this lack of employment opportunities that turned the Kopitiam into a place of ‘collective idling’, transforming kampungs into communities. Without the long hours of leisure afforded by a weak economy, most neighbours might have remained perfect strangers.

The same argument can be made for other signature elements of the kampung spirit like open doors and the spirit of mutual assistance. They were not spontaneous acts of kindness, but behaviors born of circumstance and shaped by material deprivations.

Open door policy is one of the kampung spirit’s cliches, and the nostalgic often write of a time when ‘trust made it unnecessary to lock doors.’

I do not dispute this fact, but I do find it confusing. Wasn’t Singapore dangerous and crime-ridden before LKY cleaned it up? Do Singaporeans have a genetic aversion to crime that renders the police force an unnecessary atavism?

That’s bullshit, of course. Residents kept their doors and windows open, but it was mutual surveillance that kept residents righteous. As Chua Beng Huat writes, the kampung’s confined nature meant that everyone was watching everyone else. It was thus impossible for any crime to escape justice when everyone had such an intimate knowledge of each others’ lives.

In other words, it was more Black Mirror than unspoiled Garden of Eden.

In any case, kampungs were rife with crime. Just of a different variety. Mutual policing might have prevented petty theft, but it certainly did not deter the secret societies that called the kampung their home and made it a ‘black area’ in the eyes of relevant authorities.

As historian Loh Kah Seng notes in his book ‘Squatters into Citizens: The 1961 Bukit Ho Swee Fire and the Making of Modern Singapore’, kampungs like Bukit Ho Swee were the playground of no less than a dozen gangs, including the 08, the 24, the 36 and splinter groups like the Tiong Gi Kiam, 66666 and Gi Tiong Ho.

These gangs fought each other for the right to extort kampung residents whilst supplementing their income with ‘kidnapping, robbery and murder’. Ironically, they also provided much of the kampung’s surveillance system because the gangsters rarely worked and could thus sit at the kopitiam all day to eyeball other potential criminals.

So, if open doors were born of mafia-sponsored surveillance and sociability a by-product of unemployment, did the kampung residents at least help each other out?

They definitely did. Historical records and popular memory are filled with accounts of generosity. There are stories of towkays installing lights for poor widows and villagers banding together to form volunteer fire brigades. In the government survey ‘Urban Incomes and Housing’, a young Goh Keng Swee describes an ‘extensive network of self-help’ within the community.

This, to me, is the heart of the matter. What Goh Keng Swee saw as ‘self-help’ in the 1950s has been rebranded into ‘graciousness’ and ‘goodness’ by the 1990s, and continues till today. Selective amnesia has erased the reality that our kampung spirit’s ‘self-help’ ethos was oftentimes a response to a failed state: villagers helped each other not because they really wanted to, but because there was no choice.

The volunteer fire brigade put out flames where the firemen failed to show and wealthier residents often sponsored amenities for the community to raise their social standing. Their enhanced reputation would then allow them to act as unlicensed moneylenders (a.k.a hweis) to the community.

Our official narratives have ignored this strain of pragmatism underlying acts of mutual aid. They have ignored darker voices like those of kampung resident Tay Bok Chiu: “In those days, if you could take advantage, you took advantage; if you could bully, you bullied … it was almost lawless, like ‘there was no government’.”

So, the question we should ask ourselves is this: Is a virtue born of economic necessity a virtue at all?

My answer is no.

Stripped of PR spin and properly understood, the kampung spirit is not a virtue, but to paraphrase Dr. Goh Keng Swee — a network of mutual help between residents standing in for inadequate state institutions. It’s a quid pro quo, a method of survival forged in the unique and challenging conditions of pre-planned Singapore.

It is often said that kampung life was happy despite its challenges, and people had a community despite owning little in the way of assets. What we fail to realise is that cohesion, community, and all that good stuff existed not alongside these deprivations, but because of them.

Now that we have hospitals, long-term employment, town councils and fire brigades, the kampung spirit is as obsolete as floppy disks in a 4G world. What is birthed by poverty cannot be brought back in a late-capitalist Singapore, no matter how much money we splurge on playgrounds or community hubs.

So, the kampung spirit is a myth. It is not Paradise Lost, but Paradise Invented. That being said, every country needs its national myths: America has American exceptionalism and post-Brexit Britain has defined itself as anti-europe. The problem with the kampung spirit as a national myth is not its imaginary nature, but it’s lack of relevance/credibility in a Singapore that has been changed beyond recognition.

In 2018, communities are no longer bound by the geographical confines of a village. The institutions that bind us are schools, corporations, alumni networks, gyms, social media interest groups, etc. Kampung residents looked to their neighbors for help, but our modern-day neighbors are more often found on Whatsapp or Instagram rather than down the corridor.

Furthermore, the younger generation has scant experience of kampung life except as a romanticised era in the distant past. All the Mediacorp dramas and preachy editorials in the world cannot resurrect the social conditions that made necessity resemble morality.

It’s time for an update. Social cohesion, community spirit and neighborliness are values well worth fighting for. But their existence does not depend upon the myth of the kampung spirit.

It’s time we build ourselves something new.

Have something to say about this story? Write to us at community@ricemedia.co.