All images by Xue Qi Ow Yeong for RICE Media

“A single hanging of a drug trafficker is a tragedy; a million deaths from drug abuse is a statistic.”

That was the analogy Minister for Home Affairs and Law K Shanmugam used in a 2022 BBC interview to describe media coverage of the death penalty in Singapore.

With the recent initiatives to shine a light on the victims of drug abuse, spearheaded by the Inter-Ministry Committee on Drug Prevention for Youths, we see an attempt to shift focus to the other side of the story—the lived experiences of those who suffer as a result of drug abuse and trafficking.

Mr Shanmugam announced in Parliament that Drug Victims Remembrance Day would henceforth be observed on the third Friday of May each year. This year’s inaugural Drug Victims Remembrance Day on May 17 was also marked with the launch of a roving exhibition. After a stint at Ngee Ann City Civic Plaza, a smaller version of the exhibition is set to traverse the heartlands of Singapore from May 24th to June 21st.

After years of laser focus on prevention programmes (remember those “Say ‘no’ to drugs” assemblies in school?), this feels like a step forward in furthering nuanced discussions on drug abuse.

After all, we’ve seen a rise in young drug abusers and more “permissive attitudes” towards drugs, according to the Central Narcotics Bureau (CNB). Perhaps, with younger Singaporeans, education in lieu of fear may be more effective in turning them away from narcotics.

Beyond what they see of drug abuse in the media (think cult favourite series like Breaking Bad and Euphoria), the majority of Singaporeans aren’t likely to have any experience with drugs—nor any firsthand experience of the impact of drug abuse.

This exhibition and the gazetting of Drug Victims Remembrance Day seem to be an effort to correct the misconception that drug abuse is victimless.

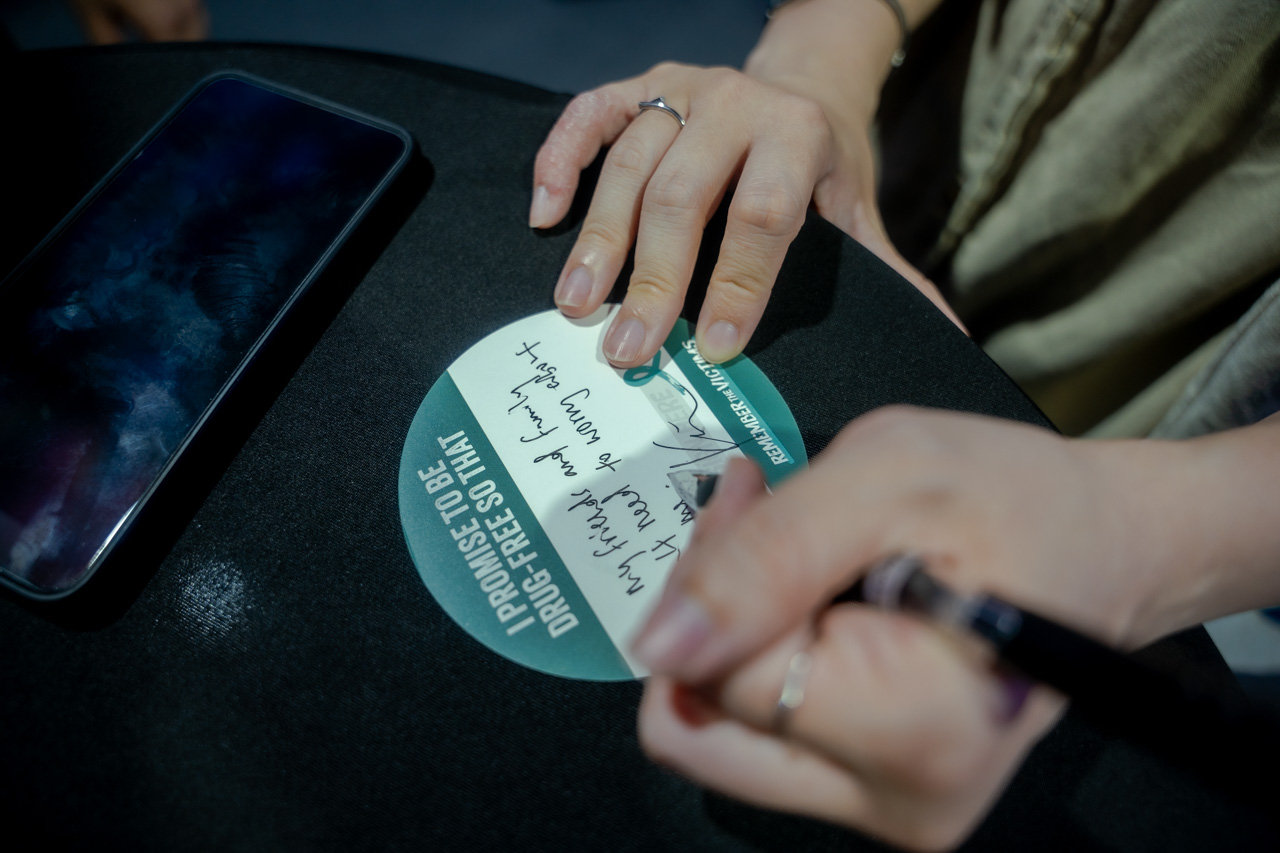

As a drug abuse prevention strategy, it seems to be working. Over 79,000 pledges to remain drug-free have been made, CNB said on May 18. These are simply pledges, nonetheless.

But as a means of illustrating the lives and stories of people affected by drug abuse, it felt like there was room to delve deeper.

Take the Candles for Victims exhibit, for example. The display is an attempt to paint a picture of just how deadly drugs can be. According to the World Health Organization, 600,000 lives worldwide were lost to drug abuse in 2019 alone. Each LED candle is supposed to symbolise a thousand of these lives.

Beyond the candles, though, who were these people who had their lives cut short? What hopes and dreams did they have?

And if the aim was to contextualise the drug abuse victim statistics, why not focus on the 20 lives lost to drugs in Singapore last year?

The Victim Stories corner, however, presented more compelling stories. We heard from the families of drug abusers, like one woman whose father abused her. Though nameless and faceless, these real stories conveyed the devastating impact of the drug industry.

The True Drug Cases: Where Violence Meets Death segment presented more real-life violent crimes committed by drug abusers. Graphic crime scene photos were flashed on-screen, accompanied by gnarly details of the crimes.

We’re already well aware of the health risks of drugs. They’re clearly bad for you. But this segment was a reminder that innocent people can also be harmed when a drug abuser turns violent.

We heard of a man who murdered his mother and grandmother after taking lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). Another man crashed his vehicle into a bus while under the influence of ecstasy, meth, and amphetamines. Another man, a cannabis user, dunked his two-year-old daughter into water to stop her from crying, resulting in her death.

This last case, though, was a somewhat confusing inclusion. At least from previous news coverage of the case, it wasn’t mentioned if the man’s drug use had any link to his child abuse and violence.

The Home Exhibition is probably the most immersive section of the exhibit. Here, visitors step into a meticulously decorated set made to look like a typical lived-in HDB home. We get a glimpse into the chaos of a home where drugs have taken root. The effort that went into dressing this mock-up was clear, from the half-used toothpaste in the ‘bathroom’ to the toys strewn about the ‘living room’ just so.

Actors play the roles of family members of drug abusers, acting out common fears, anxieties and worries.

As a whole, the exhibition was a worthwhile visit but probably could have benefited from stronger curation and richer storytelling. After a thorough walkthrough, one question remained: beyond swearing off drugs ourselves, what can we do to help victims of drug abuse?

In a time when other countries are liberalising their drug policies, fear tactics might not be enough to scare people away from trying drugs. But educating them about what it will do to them, their families, and their community might.

At the same time, resources should also be included for people who feel moved by the exhibition to do their part for their communities. After all, as its name suggests, Drug Victims Remembrance Day should be all about keeping the victims in our thoughts.

The focus on drug victims also felt a little muddled. At times, particularly during Mr Shanmugam’s speech, the event felt more like an indictment of drug traffickers.

Before he took the stage at the exhibition launch to give his speech, video re-enactments of drug abuse victims flitted across the screen: the elderly man whose child is relapsing, the girl who’s failing her test because daddy is on drugs, the woman who’s stressed at work because her brother is using.

When it was time to address the crowd, a good chunk of his 19-minute speech was dedicated to vilifying drug traffickers.

“When activists campaign for a trafficker, who calculated and brought drugs into Singapore in order to make money, does your sympathy go towards him? Or does it go towards that little girl that you saw (in the video)?”

He later added, “We want these victims to be remembered, rather than just arguing on behalf of drug traffickers, who are the cause of the problems, who are out to make money from these killings and deaths.”

You can’t exactly have a victim without a perpetrator. And Mr Shanmugam’s speech certainly made those roles clear.

He also took the opportunity to defend the death penalty as a drug trafficking deterrent, saying, ”In Singapore, traffickers are careful. They know that we have the capital punishment, serious punishments, so either they don’t traffic, or if they do traffic, they keep the amounts small.”

Generally, most Singaporeans strongly support the death penalty. In a Ministry of Home Affairs survey conducted in 2023, roughly 69 percent of respondents said that the mandatory death penalty was an appropriate punishment for trafficking a significant amount of drugs.

Tough drug policies do indeed curb drug use and trafficking here. If we didn’t have them, we might very well have more drug abuse victims. But beyond praising the hardline policies that are already in place, we should be examining the other ways we can help them.

Maybe it’s educating people on how to talk to someone who might be suffering from addiction. Maybe it’s discussing how employers can support their employees who are dealing with these issues in their families. Or perhaps we can look into reducing the stigma against drug offenders.

And if drug trafficking is so bad, should we be doing more as a society to prevent people from falling into the trade? Socio-cultural factors come into play as well, especially when marginalisation, lack of education, and economic inequality push Singaporeans to the point of desperation.

The Inaugural Drug Victims Remembrance Day is a good effort, but it’s only the starting point. The reality is that there are many overlooked victims out there. Instead of making it about vilifying traffickers—who may also be victims of addiction—let’s have more constructive conversations on what we can do for drug victims.