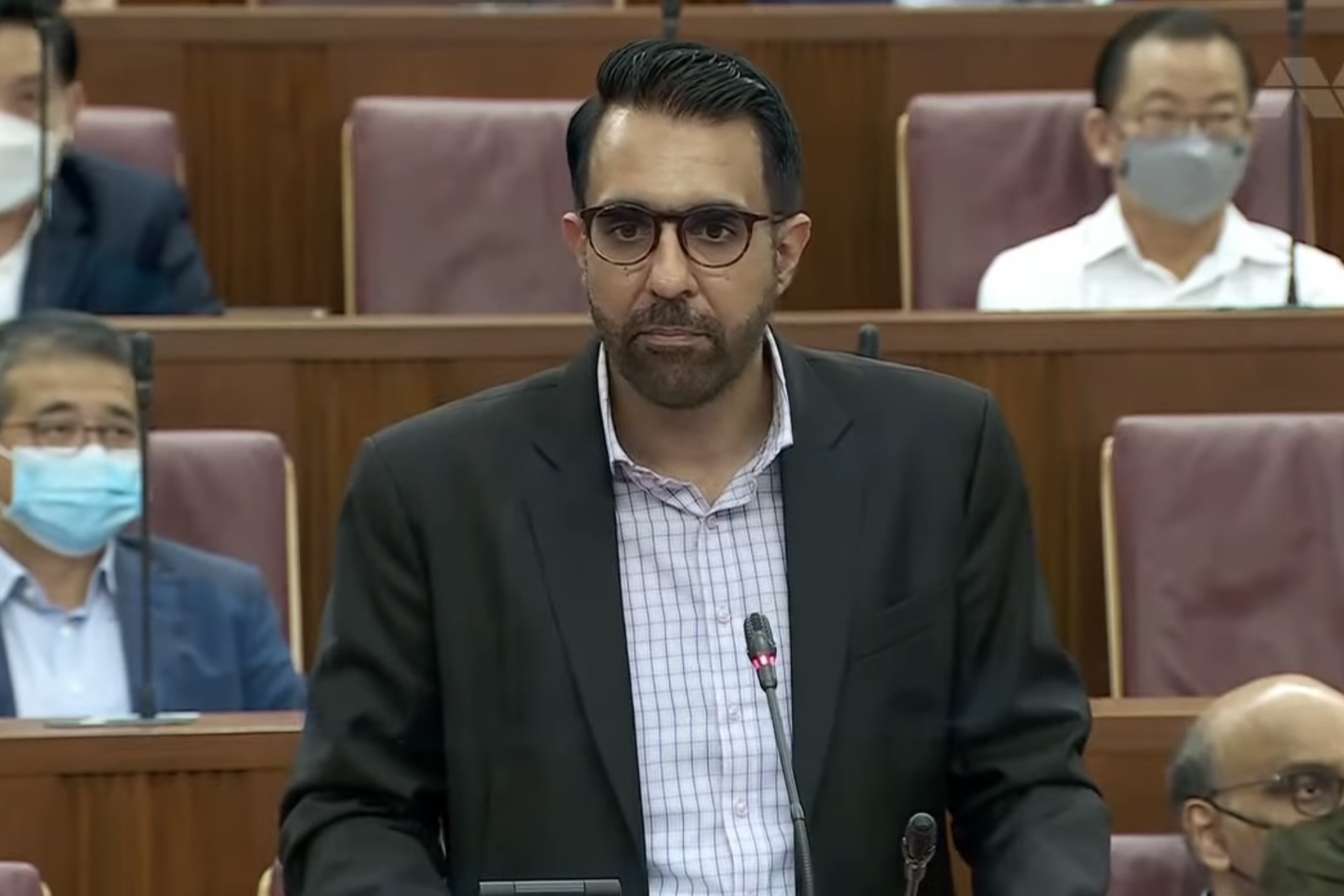

Top image: MCI Singapore

To put it plainly, the Workers’ Party chief Mr Pritam Singh’s performance in Parliament on Tuesday was a bit of a let-down.

From the outset, he promised to keep his remarks on the report of the Committee of Privileges (COP) brief because “I intend to clear my name and cooperate with the Public Prosecutor”. It was a point he repeated later: “We’re always told that when a matter is under investigation… not to comment too much.”

Perhaps that’s how we ended up with a debate in which the main subjects in the report—Mr Singh, Ms Sylvia Lim and Mr Faisal Manap—deigned to venture beyond rejecting the findings of the COP. There’s little scrutiny on how the COP came to conclude that the three MPs, especially Mr Singh, directed Ms Khan to continue lying in Parliament. Rather, the predictable charge of political persecution was made.

To recap, Ms Khan was found to have lied to Parliament three times, twice on Aug 3 and once on Oct 4. For that parliamentary misdemeanour, she was fined a total of $35,000. It could have been more, but a reduction was factored in because the COP said the three WP MPs were also liable. To wit, she carried on lying because her seniors told her to.

The lie had to do with an anecdote Ms Khan told Parliament on Aug 3 about a sexual assault victim getting short shrift by the police when the victim went to make a police report. She said she had accompanied the victim—no such thing happened. Two months later, Parliament would learn that the anecdote was something Ms Khan heard a few years ago when she was part of a sexual assault victim support group.

Mr Singh would only concede that he should have directed Ms Khan to correct herself sooner rather than give her so much time to ‘settle herself’ when he knew the truth. He said he was being compassionate and empathetic, an instinct that arises when someone confides in another about a matter as personal as sexual assault. Interestingly, Mr Singh gave a time-frame—between Aug 8 (when he first knew about the lie) and Sept 30–when he should have been more “pro-active” about getting Ms Khan to confess.

He was noticeably silent about how he sat quietly in the chamber listening to her repeating her lie on Oct 4 in Parliament. If there were a time for immediate action, it would have been then—if not contrition, at the very least, a more robust defence.

He could, for instance, have tried to talk about his initial instincts demonstrating his position on truth-telling. Or that he had wanted Ms Khan to substantiate her anecdote before she delivered the speech on Aug 3, which she didn’t do. Or that he even got her to clarify her speech later that day and helped her craft her statement in response. Still, the result was a lie repeated differently.

Reserving ammunition

On the one hand, I agree with Mr Singh that the COP did not examine Ms Khan’s behaviour and actions. The COP should have pressed on why, apart from outrightly lying, Ms Khan embellished the lie and was not moved to tell the truth even to her party chief on the very same day. She even made him complicit in crafting yet another untruth. “Why, oh why would the COP prefer to believe a confessed liar?” Mr Singh argues.

Perhaps, he was reserving fire power for a possible trial which he now seems to think is a foregone conclusion. If so, we are given no inkling about how he would conduct his defence. It seemed as though the WP had forgotten about the middle ground of voters who had yet to make up their minds about its culpability in the case and its commitment to truth and honesty. It appears that, for Mr Singh, the parliamentary session was simply another stop on the way to court.

Or perhaps he self-censored because his words in Parliament could be used by the Public Prosecutor (PP) to incriminate him. Was he worried about not having parliamentary privilege?

The motion before Parliament seems to have turned the doctrine of separation of powers on its head: the Legislature has to consider if the Executive (the PP) should investigate whether a case involving parliamentary business should be sent to the Judiciary.

The debate ended with Leader of the House Indranee Rajah’s remark that the WP MPs’ responses in Parliament could be a “strategic” or “tactical” move to focus on the ‘small things” rather than on the bigger issues of truth and integrity.

A curtain-raiser

Perhaps the reason for reticence on Mr Singh’s part could well be because he couldn’t summon sufficient arguments to clear himself.

What defence, for instance, can he possibly give for not directing Ms Khan to correct the lie in Parliament in no uncertain terms? Why, as Ms Rajah posits, this “parsing” of words? Even if he was being “compassionate”, some way could surely be worked out that would not require Ms Khan to say that she was a member of a support group for sexual assault victims. Perhaps a quiet word with the Speaker accompanied by an open admission that she heard this from a sexual assault victim she didn’t know.

It is inconceivable that he did not anticipate this line of questioning.

I had also wanted to hear how he would account for the WP disciplinary panel being composed of only members of the party who knew the truth. If the complaint was that COP was biased against the WP, WP’s own disciplinary inquiry didn’t seem that much fairer to Ms Khan or the rest of the WP members who had been kept in the dark.

Whatever the reason, he did not press the advantage that Parliament afforded him to speak freely. Instead, he repeated the charge of political persecution without much evidence to show where the key issues are concerned. To those who straddle the middle ground in the court of public opinion, the debate was merely a curtain-raiser for the main event, the PP’s entry on stage.

A fact-finding committee by any name

Still, this is not to say that he didn’t make a few good points.

Even for someone like me who followed the COP hearings religiously, I didn’t notice that the appendices to the report omitted some submitted documents. It only listed documents that the COP had referred to in its report. In other words, we have to trust that the COP had considered the additional evidence and found them irrelevant—never mind why.

Mr Singh said that the COP was “cherry-picking” points that would support its “narrative”—that he masterminded the cover-up. The COP was even ignoring contemporaneous evidence that would have put a different complexion on his involvement in the Raeesah Khan saga, he said, as he recited a few texts on WhatsApp that he had submitted to COP.

Were these the bullets he was reserving for the trial? Responding, panel member Desmond Lee tried to turn Mr Singh’s words back on him by noting that he had omitted to give the texts in full but had truncated them to provide Parliament with a positive view. He also added that those supposedly omitted evidence were in other parts of the report, like in the oral transcripts of the hearings. Mr Singh scored one with me.

Still, I found Ms Rajah’s comments on this perplexing. She described the committee as a “tribunal”, which only considered relevant evidence.

“Mr Singh’s a lawyer, I’m a lawyer,” Ms Rajah intoned. “He knows that evidence that is given is considered by a tribunal whereas relevant evidence is referred to. Not all evidence that is put in is relevant, and when you write your final report, you refer to relevant evidence,” she added.

Ms Rajah added that the evidence included many documents submitted by the WP leaders. If they felt that something was relevant or not taken into account, Mr Singh will have the opportunity to refer to it if the matter goes to court.

So, is the COP a fact-finding committee or not?

On weaponising

It takes very little for the committee to append all documents in its already voluminous report—whether they were considered or not. After all, the COP laid stress on the transparency of the process by allowing televised hearings. Recall when a parliamentary committee was convened to look at possible fake news laws, all representations of it were made public, whether or not they were taken into account.

She said the WP was trying to cast aspersions on the work of the COP. But what was Mr Desmond Lee’s insinuation when he suggested that a draft report of the committee had been leaked to Mr Singh? He had seized on a word that Mr Singh used about how the COP had “weaponised” the issue of mental health.

This word, Mr Lee said, was in an earlier report that was redacted in the final.

His repeated questioning flummoxed Mr Singh, who said he would check the word’s genesis. In the end, he said he might have recalled reading it in an article in this publication.

It was a timely opportunity to berate Mr Lee for insinuating that the only WP member, Mr Dennis Tan, had acted dishonourably in giving Mr Singh sight of the draft. It was uncharacteristic of Mr Singh and the WP not to have leapt at such an opportunity to turn the tables on the PAP.

I am glad, however, that Mr Singh took issue with the COP’s characterisation of his comments on Ms Khan’s mental health condition.

“I reject this assertion that in raising the matter of Ms Khan’s mental health to a fact-finding body with a view to considering an appropriate punishment on her, I had somehow smeared her, or worse, somehow cast aspersions on those with mental health conditions,” he said.

He pointed out that it was Ms Khan who had mentioned this, and he thought telling it to the COP might serve to mitigate any penalty that could be meted out to her for lying.

I am glad because going by the COP’s comments, it would appear that it is inappropriate for anyone to say anything about another person’s mental condition, even if it was germane to attempts to find the truth.

That cannot stand. Just as it cannot stand that a lie can be told so long as the motivation behind it is good.