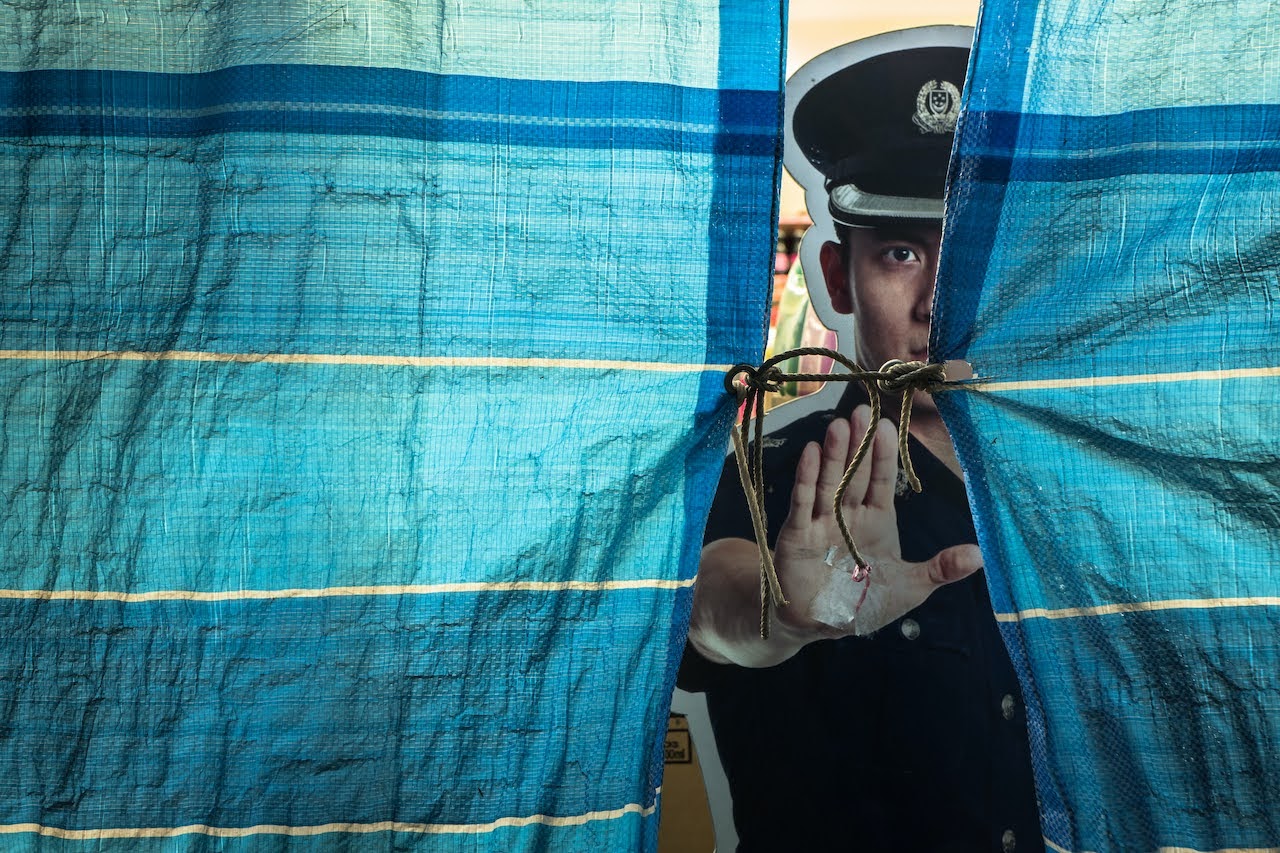

Top image: Julian Wong / RICE File Photo

If you haven’t committed a crime, there’s no need to fear the police. That’s how I was raised, and so were most Singaporeans, I’m sure.

It’s also the underlying principle behind a new Bill that, if passed, could give police officers more powers to conduct searches without warrants.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Criminal Procedure (Miscellaneous Amendments) Bill 2024 was announced by the Ministry of Law (MinLaw) and the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) in a press release on January 10. The bill is set to be a subject for debate (and there’s much to debate about) in Parliament at a later date.

The Bill contains several proposals by MinLaw and MHA that aim to update and enhance the powers of the police and other law enforcement agencies. The government regularly reviews Singapore’s criminal justice laws to ensure that they’re “up-to-date and fit for purpose”, MinLaw and MHA note in their joint press release.

Currently, searches without warrants are permissible if a police officer has grounds to believe the accused will not produce relevant evidence, even under a warrant. However, the problem here is that it isn’t straightforward to determine, the ministries say. Uncooperative suspects can hamper investigations by delaying searches or tampering with evidence.

To address that, the new Bill proposes for officers to be allowed to search suspects of arrestable offences if they have reason to believe that they possess or have power over relevant evidence.

Besides the search without warrant thing, the other proposals include empowering the police to search arrested persons to remove dangerous items such as razor blades and needles from them and requiring accused persons to undergo forensic medical examinations (FME) when relevant (think serious sexual offences such as rape).

Theoretically, the merits of this new Bill are clear, especially in cases of crimes such as sexual assault allegations. Criminals are less likely to walk free if it’s easier for law enforcement to secure proof of their guilt.

But we have to be aware that giving the police more power to act without warrants comes with a trade-off. As private citizens, are we essentially giving up some of our rights?

As it stands, we’re likely to only get into the nitty-gritty of this new Bill when it’s debated in Parliament. But these are the questions we hope will be answered then.

Who Decides When or Why Suspects Are Searched Without Warrant?

For example, under the same Bill, the proposed legislative framework for FME specifies that only Police officers holding at least the rank of Inspector have the power to require inspections involving intimate parts.

It does sound, however, like the power to conduct searches without warrants on suspects extends to all police officers.

Instead of having to demonstrate to a court that the search would serve the purpose of justice (which is what happens when a regular search warrant is issued), police officers might find themselves in more situations on the ground where it’s their judgment call.

ADVERTISEMENT

How does an officer decide that there’s “reason to believe” that a suspect might have evidence that they’re hiding?

What stops an officer from searching a suspect because of profiling or the way they’re dressed?

What Are the Safeguards Against Abuse?

As much as we do trust the authorities, there are bad apples. Many police officers do good work. But some are capable of molesting, misappropriating funds, and more. These bad apples are righteously dealt with upon discovery of their misdeeds.

That being said, will there be safeguards in place to protect citizens from being unjustly or unfairly targeted by law enforcement?

Under the new Bill, obstructing a police officer from carrying out a lawful search is an arrestable offence that carries a fine of up to S$5,000, up to six months’ jail, or both. What recourse does a citizen have if they have reasons to believe they’re being searched unfairly? After all, if they refuse to be searched for any reason, they could very well be arrested.

Why Exactly Do the Police Need More Power?

We haven’t gotten any concrete statistics or case studies to justify the need to enhance the police’s powers. These will be unpacked in Parliament soon, no doubt.

The only reason for the amendment (so far) is that it’s too hard for officers to determine whether searches without warrants can be conducted under the current law.

What triggered this move? Are the current powers given to police inadequate?

Every citizen deserves due process. Unfortunately, this does take time. If there’s a strong, timely argument for amending laws to give the police shortcuts in the name of “greater operational efficiency” (to use the ministries’ own words), it should be public knowledge.

Is The Need To Enhance the Police’s Powers More Important Than Our Right to Privacy?

The new proposals are eyebrow-raising, to put it mildly. But the other thing giving us pause is the win-win outlook of it all. At a media briefing on the new Bill, Law and Home Affairs Minister K Shanmugam explained:

“There is no downside to this amendment because if they search and they find the evidence, or if they do not find the evidence, no one is worse off.

“And, if challenged, the police will show you why they reasonably suspected the person to have the evidence. This would make things easier for the police and law enforcement agencies on a day-to-day basis.”

Essentially, if citizens have nothing to hide, why should they be afraid of getting searched?

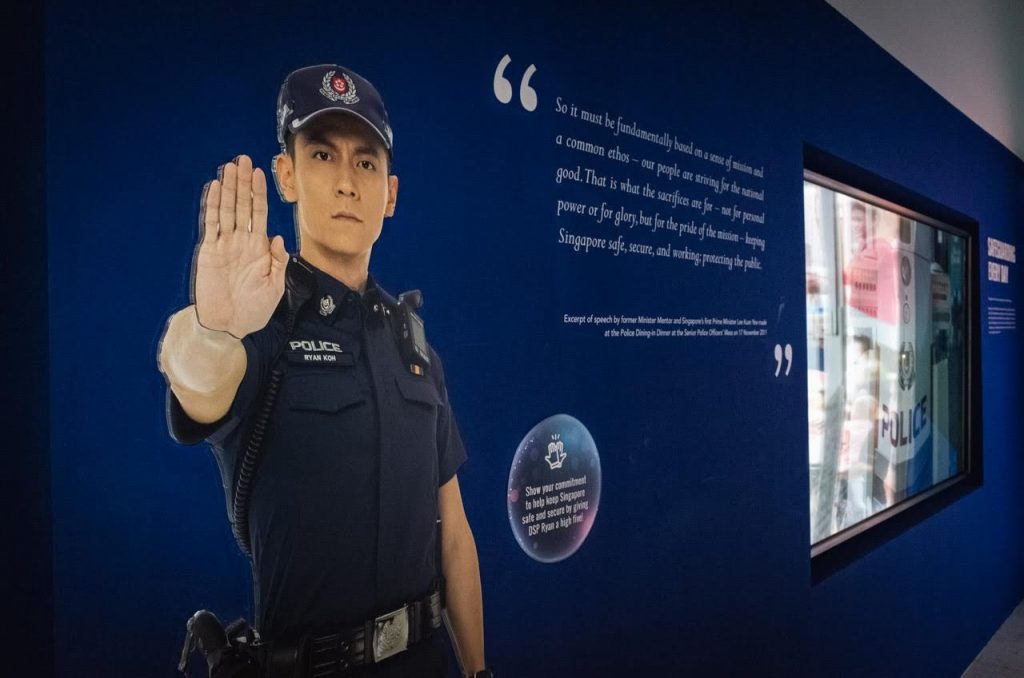

This ‘nothing to hide’ mentality is one that law enforcement has also espoused. Superintendent Roy Lim, who is head of the Special Investigation Section, suggested establishing a national DNA database in a 2022 interview with CNA in order to solve and deter crime.

When asked about the possible privacy concerns, he mentioned that these issues were due to Western influences.

He added: “But to me, if you don’t commit a crime, why are you afraid?”

This line of thinking isn’t convincing enough, especially today. If anything, it doubles down on Singapore’s reputation for being a surveillance state. Even if we haven’t done anything wrong, there’s a natural distrust when one can be scrutinised and physically inspected anytime with ease.

Most of us would bristle at the thought of an employer installing tracking software on our computers—it doesn’t matter if we’re slacking or not. We’d also hate the thought of our parents opening our mail, even if they’d likely find more junk mail than anything sensitive.

How would we feel about the likelihood of getting searched without a warrant?

The Remaining Rights We Have

Even if a person is accused of an arrestable offence, there’s always a chance of them being innocent. Is an innocent person whose privacy was invaded by a police search really not “worse off”? What about the personal distress they’d likely go through?

To justify it all, it’s a matter of proving that the tangible benefits of such measures will outweigh the compromises Singaporeans have to make.

The very reason warrants—court orders issued to the police—exist is to protect private citizens from unreasonable search and seizure.

If we’re going to do away with them in some situations simply because they take too long, there needs to be transparency on protocols and operating procedures.

We need to know the parameters of these searches, the (remaining) rights we have and get clarity on accountability if anything goes awry.

Singapore is safe. A large reason for this safety has to do with the privacy we’ve given up—we go about our days with hundreds of thousands of police cameras watching us, and we don’t bat an eye.

But it is worrying if we’re simply asked to subscribe to this ‘if you’re innocent, you have nothing to hide’ mentality and be okay with it. It’s also worrying if, at the end of the day, the public unquestionably accepts another potential intrusion of privacy in their lives here.