Top image: Solace Asia / Facebook

When finding solutions to tricky, all-encompassing societal predicaments like addiction, the coarser, unambiguous path is the one most taken.

Don’t like smokers because of the tobacco-related deaths every year? Raise taxes and raise the legal tobacco purchasing age. Don’t like drug addicts on the streets? Well.

In Singapore, these approaches have been (and still are) applied with hard-nosed practicality. ”There is no use having beautiful laws, embodying the noblest ideals, only to do something else in practice,” mentions Minister of Law and Home Affairs, K Shanmugam, regarding the Rule of Law here.

This pragmatism bleeds into the policies enacted against harm to society and individuals. Strategies based on prohibition and harm eradication are effective, as the national stance goes. Liberal approaches are “reckless, irresponsible,” Minister Shanmugam says.

Even so, there’s been a worrying trend of young drug abusers of late. People are succumbing to addiction despite tough laws and tougher enforcement.

Perhaps the concept that doesn’t get as much attention is that addiction (to anything) is a journey, not something that you can just switch off like a light. It might not even have an end, even if the addict makes conscious efforts.

Across Southeast Asia, abstinence has been the driving force for legislation—even now as harm reduction tactics take root in the West. The pursuit of harm eradication has been costly, contentious, and at this point in time, never-ending. Can we still believe that this approach is pragmatic in the long run?

The old ways of clamping down hard on substance abuse have to change, industry experts agree at a two-day conference in Kuala Lumpur. In the Evolving Treatment Methodologies in Addiction (ETMA) conference held in July, academics, scholars, doctors, and scientists argue that the world has to start thinking along the lines of sustainable recovery.

Addiction is a complex chronic disease that requires nuance in comprehension to properly treat. If that’s the case, they say, we need more progressive approaches that embrace nuance too.

Through statistics and evidence-driven effusions, these Malaysians argue that policymakers need to take a step back and have better clarity on the root causes of various addictions. And more importantly, refining policies in response to modern research and viable alternatives for sustainable recovery.

‘We Are Not Evolving’

“We’ve had the war on drugs for more than 50 years—have we destroyed drugs or have we destroyed family institutions?” Malaysian lawyer and advocate Samantha Chong asks in a forum about the evolution of drug policies. Putting people in jail for drug abuse and trafficking creates a vicious cycle when they can’t get jobs after their release, leading them to fall back into crime.

While that may be an issue with our neighbours, the way Singapore prevents this cycle is fairly rounded. Here, we employ mandatory evidence-based rehabilitation methods, aftercare counselling and community support to reduce the risk of relapse among drug abusers.

Perhaps the right approach, Samantha says, is to ask why people get into drugs in the first place, like what Thailand did. The country saw a problem in its most rural parts, where farmers cultivated poppy crops out of survival—they live in areas without infrastructures, and most can’t get jobs because they don’t have identity cards.

One solution is alternative development. Agricultural assistance, market access support and infrastructure enhancement by the Government of Thailand gave these farmers a stable income and better opportunities for their children to attend school. Addressing the root reason brought a significant decline in poppy cultivation in Thailand.

“From my experience, we are not evolving,” says Associate Professor Dr Rusdi Abdul Rashid of the University Malaya Center for Addiction Sciences. The vicious cycle created by strict criminalisation of drug abuse has led to Malaysian drug laws being more dangerous than the actual drugs themselves.

“Drug abusers are patients, they’re not criminals,” he affirms. “We should try something else instead of repeating the same thing all over again,” Dr Rusdi continues, pointing to the possibilities of decriminalisation in lieu of prohibition.

Within the same panel discussion, Professor Dr Sivakumar Thurairajasingam of the Clinical School Johor Bahru Monash University Malaysia brought up something that’s not often considered in policies: human rights through harm reduction. The building block of being human, essentially—giving people the ability to choose.

“Harm reduction is a range of pragmatic policies or regulatory actions. What it does is reduce risk. Health risks. It gives you an option to a safer choice—or maybe encourages less risky behaviour.”

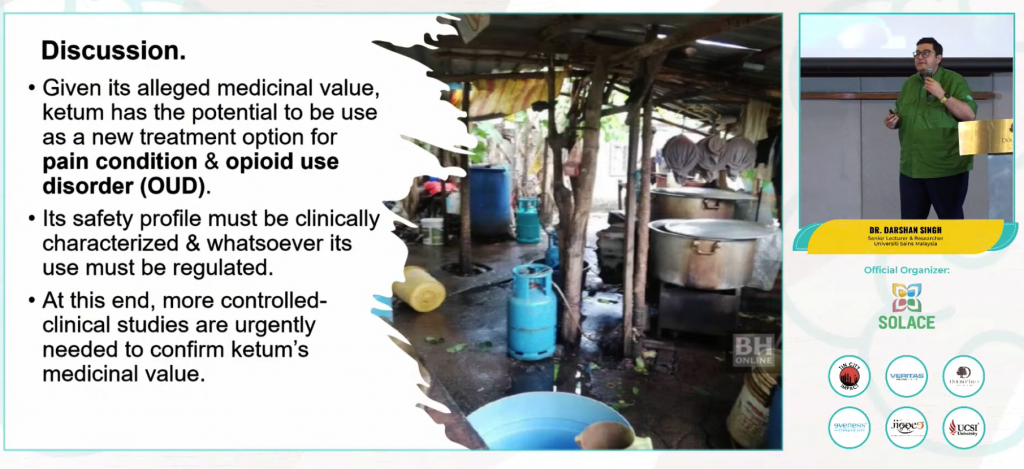

The argument against outlawing potential harm-reducing alternatives came strong in a speech by Dr Darshan Singh, a University of Science Malaysia senior lecturer who has been researching heavily about kratom usage. The leaves of the kratom plant have been traditionally used by farmers and labourers in the rural parts of Malaysia as a stimulant (at low doses) and pain relief (at higher doses).

The researcher points out that kratom does have medicinal value, despite its mainstream perception as a dangerous plant. According to his studies, drug abusers seeking self-treatment have been using kratom to suppress withdrawals while also reducing the intake and frequency of drug use—ultimately promoting abstinence.

Such is the potential to pave the way for sustainable recovery. But it’s something that’s unlikely to happen here. Singapore focuses on building a drug-free society, not a drug-tolerant one.

The Nuances of Nicotine

Hard drugs aside, another hot topic relevant to us is, of course, the ongoing hubbub about smoking and its adjacent cousin, vaping.

Smoking will kill you; that’s a no-brainer. The path to going smoke-free makes sense, like what New Zealand is doing. But the mistake most policymakers are making right now, however, is conflating nicotine and combustible tobacco as one singular vice, Australian MP Fiona Patten says.

In a discussion with Adjunct Prof. Dr Prem Kumar Shanmugam, the Clinical Director and CEO of Malaysian addiction treatment centre Solace Asia, she mentions that there is a notable lack of conversation around the viability of vaping products.

“Looking at nicotine is one thing, but looking at combustible tobacco—that is what kills you. You take combustible tobacco to get the nicotine, but it’s the combusting tobacco that’s going to kill you.”

This nuance is disregarded when it comes to Singapore’s stance against tobacco alternatives. While Fiona argues that there is a significant difference to consider between smoking tobacco and consuming nicotine, Singapore considers them to be equally dangerous. Going smoke-free means being nicotine-free too—something that Fiona will likely determine as “problematic”.

Nicotine is a highly addictive stimulant drug that “primes users to the use of other addictive drugs,” the Ministry of Health asserts. While the current national perspective declares that there is insufficient evidence to make a firm conclusion, at least there is an ongoing review on the efficacy of e-cigarettes in smoking cessation.

But this abstinence-based approach creates other issues. Fiona points out that the complete prohibition of vaping in her home country has created a black market for the products—an “appalling” situation that forces smokers to continue smoking when there is a safer (but not harmless) option to consider.

Plus, it allows organised crime to fester because of the high demand for alternatives. This should be familiar for those in the know in Singapore: there are easy, accessible ways to obtain e-cigarettes if you’re actively looking for them. Black markets thrive when consumer demand overlaps with hard regulation.

New Zealand got it right, says Fiona, where smoking rates have gone down thanks to regulation. Smokers can choose alternatives when they can get vaping products from licensed shops where only adults can make purchases.

It’s a stark contrast to Australia, where smoking rates have “plateaued”. In Singapore, smoking rates have indeed tapered marginally since the last count in 2020. While there have been no comparable figures for the smoking quit rate in the past two years, local vape cases have increased.

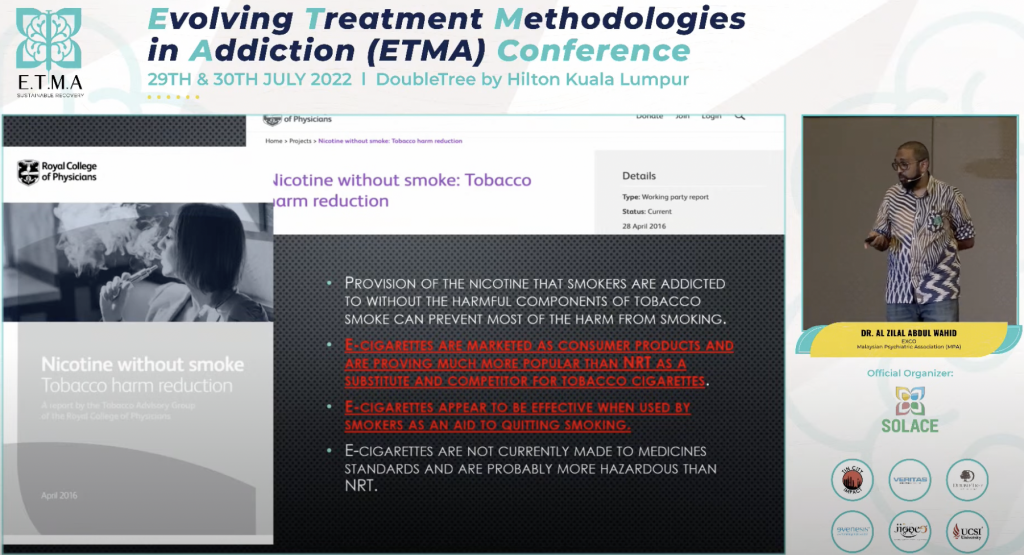

Dr Al-Zilal Abdul Wahid, a member of the Malaysian Psychiatric Association who has been working closely with the University Malaya Centre of Addiction Sciences, lays out multiple medical studies that evidence the practicality of vaping for smokers wanting to quit cigarettes.

One issue, according to a study by Cancer Research UK, lies in public perception. The mismatch between public perception toward vaping doesn’t match the evidence that vaping is a far safer alternative—e-cigarettes are unlikely to exceed 5 percent of the harm from conventional smoking.

The prevalent thought: Children will start vaping too if it’s legalised. This, despite 4 percent of kids who’ve never smoked before were found to have tried e-cigarettes, and out of this group, only 1 percent became regular users in the UK in 2016.

“This actually rebuts the thought that young people will start vaping. My question is: What makes you think they won’t start smoking? It doesn’t makes sense right?” Dr Al-Zilal puts forth.

Dr Al-Zilal also points out that the current state of vaping is different than it was previously. There were legitimate fears of people messing with the liquid solutions, which are heated up to produce the inhaled vapour.

These days, vaping devices use closed pod systems where the liquid solutions are sealed in cartridges with no easy tampering by users.

“If we can regulate it now with the closed pod systems, we can start [allowing] this amount of nicotine from this country; this propylene glycol of this quality can be made in this kind of factory; approved and prescribed by GPs or addiction psychiatrists.”

Because e-cigarettes are currently not produced according to medicinal standards, there’s a higher probability that they might be more hazardous than other nicotine replacement products, he argues.

“If we can regulate it, why not?”

The Opposite of Addiction is Connection

There’s something commendable to note about Singapore’s steadfast stance on erasing addiction of all kinds while the rest of the world is slowly losing faith in the war on drugs. And when learned Malaysian academics are going to great lengths to question their country’s existing policies to help addicts, it’s surprising (but not really) that their neighbours down south aren’t doing the same.

There are pros and cons to harm eradication, just as much as there are for sustainable recovery. Regardless of where you sit on the spectrum, anyone can agree that treating everyone humanely is only right. The opposite of addiction—isolating by its very nature—is not sobriety, as British-Swiss writer Johann Hari notes in his book about drug policies. It’s human connection.

Throughout the various speeches made at the conference, the common pattern lies in correcting the way we’ve been treating addicts. They’re not outcasts, nor should they be viewed as such. The path toward recovery has many forks, but all the good ones are paved with dignity, empathy and nuance.