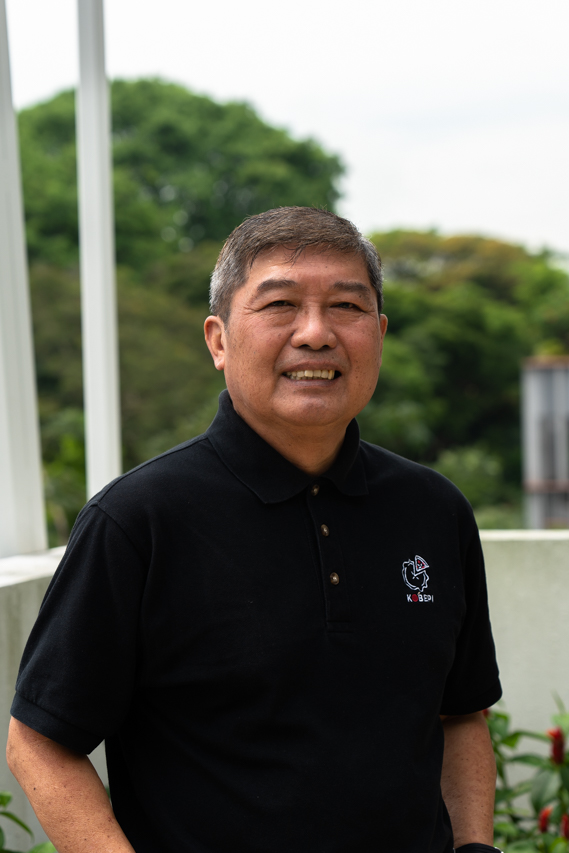

Top Image: L. Junji / KobePi

Junji Lim was at a crossroads in 2006. He had to decide the fate of his brainchild, Oishi Japanese Pizza—a homegrown pizzeria selling pizza with Japanese culinary toppings.

Splashed across its menu, against a backdrop of red distinctly similar to the circle on the Japanese flag, were its bestselling flavours: Teriyaki beef, green tea chicken, and wasabi seafood. Its flagship outlet, opened in 2003, was nestled at Gillman Barracks.

The meteoric rise of Oishi Japanese Pizza was not enough for Junji. There were two options: Continue on the current trajectory and grow the business by himself or relinquish control to a multinational company armed with the expertise to grow his business much faster than he ever could.

The brand spread across the island within a few years. By 2006, Oishi Japanese Pizza had eight outlets, a central kitchen, and a call centre. Back when omnipresent food delivery services were yet to be a thing, a call centre was the mark of a successful food business.

He made his choice—one that he would later regret. Today, at 62 years old, the man is baking an entirely new Japanese fusion food empire.

The Dough Maker, Junji Lim

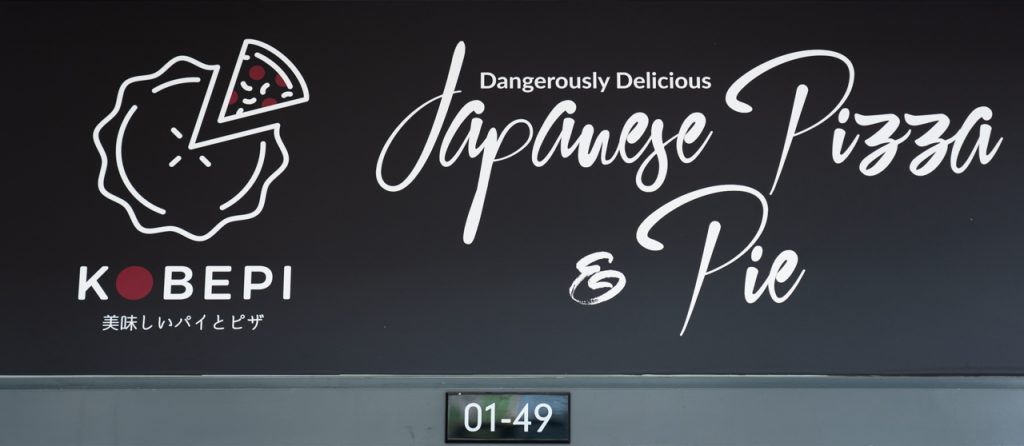

“Konnichiwa,” Junji chirps, flashing a smile as I enter his bakery. He is dressed in an unassuming dri-fit shirt that bears the logo of his latest business venture, KobePi. His workman boots thud against the ceramic tiles of Urban Vista, a condominium in Tanah Merah where KobePi’s lone outlet is located.

The store is tucked away along a stretch in the condominium, located close to its back gate facing Tanah Merah MRT station. It’s yet another personal business venture. Junji estimates that he and his business partners have invested close to half a million dollars into KobePi.

Radiating from his bashful energy is a love for Japanese culture and food. In fact, Junji is an adopted name. He goes by JJ Lim in his previous life as a resort and country club developer.

“Back in the ‘80s, Japanese music and artists were trendy. I enjoyed Teresa Teng, but soon found out most of her songs were adapted Chinese renditions of popular Japanese origins.”

“It was once difficult to find Japanese restaurants in Singapore. Japanese food culture only became prevalent in Singapore 25 years ago after the arrival of Sakae Sushi,” Junji recounts.

A singular counter greets customers when they enter. Along the counter is a row of devices bearing the names of different food delivery companies. The outlet is the size of a neighbourhood corner shop, about 420 square feet.

An industrial oven looms ominously behind, whirring and humming along. Two staff members shuffle around the food preparation area right next to it.

Aside from the only splash of vibrant colour from a poster, the grey interiors of KobePi bear a resemblance to an industrial kitchen. Junji takes a seat at the outlet’s only table—a waiting area for customers. “When I had my first taste of wasabi in a chic Japanese restaurant, I thought it tasted like turpentine.”

Yet the piercing aftertaste of wasabi did little to stop Junji from falling in love with Japanese food and sharing his passion with his children.

“I introduced my children to Japanese food. My children love sushi and sashimi, just like me. They also liked Pizza Hut; they were my inspiration to start Oishi Japanese pizza.”

The Rise and Fall of Oishi Japanese Pizza

Junji says he made the wrong choice when deciding the fate of Oishi Japanese Pizza in 2006.

On one hand, he so desperately wanted to keep a business which kept him close to his children and family. On the other hand, he knew he didn’t have the expertise and resources to mould Oishi Japanese Pizza into a bonafide titan that could compete with the likes of Pizza Hut and Canadian Pizza.

He chose the latter: Selling complete control of Oishi Japanese Pizza to ABR Holdings (Swensen’s Singapore, Tip Top Curry Puff, etc), retaining only a small amount of shares in the business as a symbolic gesture.

However, Oishi Japanese Pizza took a turn for the worse after he relinquished control of the brand to a multinational company. Slowly but surely, Oishi Japanese Pizza’s identity was diluted.

Non-Japanese flavours, like Hawaiian and Pepperoni, were introduced to appeal to a wider audience. Regular customers lamented its identity crisis. Potential patrons were confused about what Oishi Japanese Pizza was trying to be. Casual observers smirked at its downfall and weaved cautionary tales to small business owners considering selling out for a quick profit.

Junji shifts in his seat, a triangular chair shaped like a pizza slice. He turns his attention towards the counter. No online orders have come in yet.

“I didn’t have immediate regrets when I sold Oishi Japanese Pizza. I was promised that the company would grow the brand to be large enough to franchise,” Junji glances at the counter again. Still no orders.

“The regret kicked in only after a few years when I realised the slow demise of the brand. The company did not manage the brand well. I learned a valuable lesson: You should never adulterate your Japanese brand.”

A Slice of a New Beginning

A brown, coarse bag of flour shipped directly from Kobe, Japan, is carefully hauled into the preparation area like precious cargo. Each bag of flour costs about $40—a few dollars more than regular flour. According to Junji, Kobe flour is his secret ingredient, which adds to the flaky texture of his pies.

KobePi’s menu boasts a selection of seven pies and eight pizzas. Its current pizza recipes were adapted from Oishi Japanese Pizza—a homage to Junji’s past venture.

“In today’s food industry, we see more fusion food between the East and West. We hope to ride this wave and blend Western food ideas with Japanese flavours.”

The industrial mixer chugs along—they have been churning dough since 10 in the morning. KobePi opens six days a week, closing only on Wednesdays. Junji shuffles out of bed at the crack of dawn each workday, takes a morning drive to KobePi, unlocks its doors, and runs through his array of food delivery devices.

In another life, he would have been frolicking the fairways of golf courses with a nine iron in hand. Junji figures his retirement would have been spent on the green.

Yet, here he is, anxiously fretting over the devices and checking his online orders again on his iPad. “After Oishi Japanese Pizza was sold, I developed resort properties and managed golf resorts and hotels for Keppel Land China. But something had always bugged me. I knew I had unfinished business.”

This, despite his achievements in property development. The man was involved in the development of Katong Village along East Coast Road, and managed Arena Country Club in Jurong and Spring City Golf Lake Resort in Yunnan, China.

Even after an illustrious career, Junji could not live with the regret of the demise of Oishi Japanese Pizza.

“I dreamt of contributing to the local food industry. After travelling in China, Taiwan, and Japan, I returned to Singapore to build KobePi. I want KobePi to be a homegrown success, something that Oishi Japanese Pizza was working towards before its decline,” Junji remarks.

When asked if he ever dreams of retirement instead of slogging out his 60s in a kitchen, Junji smirks. His business partners are at least 70 years old. Retirement, to him, is out of the picture.

Junji pauses and squints at his iPad. He quietly recites the steps to navigate a complicated online order system under his breath.

“Many do not realise that KobePi was started by a Singaporean. Had Oishi Japanese Pizza been successful, I would have been happier. I would not have started KobePi.”

Lightning Rarely Strikes Twice

Junji expected hiccups in his second business venture, KobePi. After all, Oishi Japanese Pizza’s prolific rise as a homegrown brand is difficult to replicate today.

Singaporeans have, at their disposal, an array of Japanese food brands to choose from. The pizza market is now dominated by many more household names than a few years ago. Singaporean palates have evolved—we’re now more willing to visit upscale cafes and expensive eateries.

However, Junji did not expect the KobePi journey to be as difficult as it has been. “We opened in 2017 with an outlet at Somerset and a kitchen at Tai Seng Industrial Avenue. However, we closed in 2019 because of COVID. We could not afford the rent.”

“Things were good in the first few weeks at Somerset; there were long queues and there was a buzz,” he recalls, serving me a hot Japanese curry beef pie straight from the oven.

“We lost $300,000 and our equipment—money we raised from investors and my own savings. We did retain the name and rights to KobePi. Also, it’s hard to get the word out. Social media is so important. An F&B business lives and dies by what is shared about it online.”

The umami of the Japanese curry complements the tanginess of the melted mozzarella cheese. The flaky golden brown pie crust crumbles and crackles with the slight prod of a fork. It’s surprising KobePi has yet to take off like Oishi Japanese Pizza did.

“When you have no manpower, you have to do everything yourself. My wife helps to improve the recipe for the dough. I develop the business and run the operations along with my team,” Junji looks on, happy with the pie he just served.

“My friends have stopped calling me for golf because they know weekends are when the action starts. We only get about 20 to 30 customers on a weekday, but much more on weekends.”

No Easy Recipe for Success

The shop is quiet, save for the two staff members in his team kneading dough—the KobePi team only has three employees. The current outlet is Junji’s third crack at growing the business. KobePi is a reluctant nomad, moving from place to place to keep its head above water.

“We moved to Aqueen Hotel in Paya Lebar for about a year. We moved to this place in September last year—the rent and the utilities are much cheaper here. It’s about $1,000 or less in rent, compared to the $5,000 I paid at the hotel,” Junji explains. The whir of the oven tails off.

“I need to pay my workers. I’ve forked out about $100,000 from my own savings to pay my staff and to keep this outlet afloat. When I want to do something, I want to make it successful.”

In his private moments, his decision to surrender control of his brainchild haunts him like a spectre. His friends questioned him about Oishi Japanese Pizza’s trajectory after its closure. He could barely muster a response to them.

“Looking back, the product was probably first in the region. It was a successful business. But life is sometimes like golf. Sometimes you need a few more strokes, but you’ll get there. You just need to be brave enough to fail.”

By typical Singaporean metrics, Junji is a man who has already achieved success. After a lucrative career, he could have easily spent the rest of his days golfing with his buddies and travelling the world.

And yet, he persists, chasing his unfulfilled ambition of nurturing a homegrown success—indicative of the larger Singaporean dream of never settling for less. Failure isn’t an option.

A Toast to Butter Days

It’s midday. Their first customer of the day walks in—a condominium resident. Junji springs up from his pizza-shaped seat and greets her with the same chirpy “konnichiwa” he offered me.

“Hello, I’ve ordered online, but I’m not sure whether you’ve received it,” she admits sheepishly.

Junji squints at his iPad again, scrolling through the inventory of orders. Again, under his breath, reciting the steps to navigate and find the online orders for KobePi. He doesn’t find any orders.

“Yes, I am so sorry there may be a problem with the system,” his concentration breaks into a relaxed, customer-facing demeanour.

“Arigato gozaimasu. Please let us prepare the order for you now,” he flashes another smile before an apologetic bow.