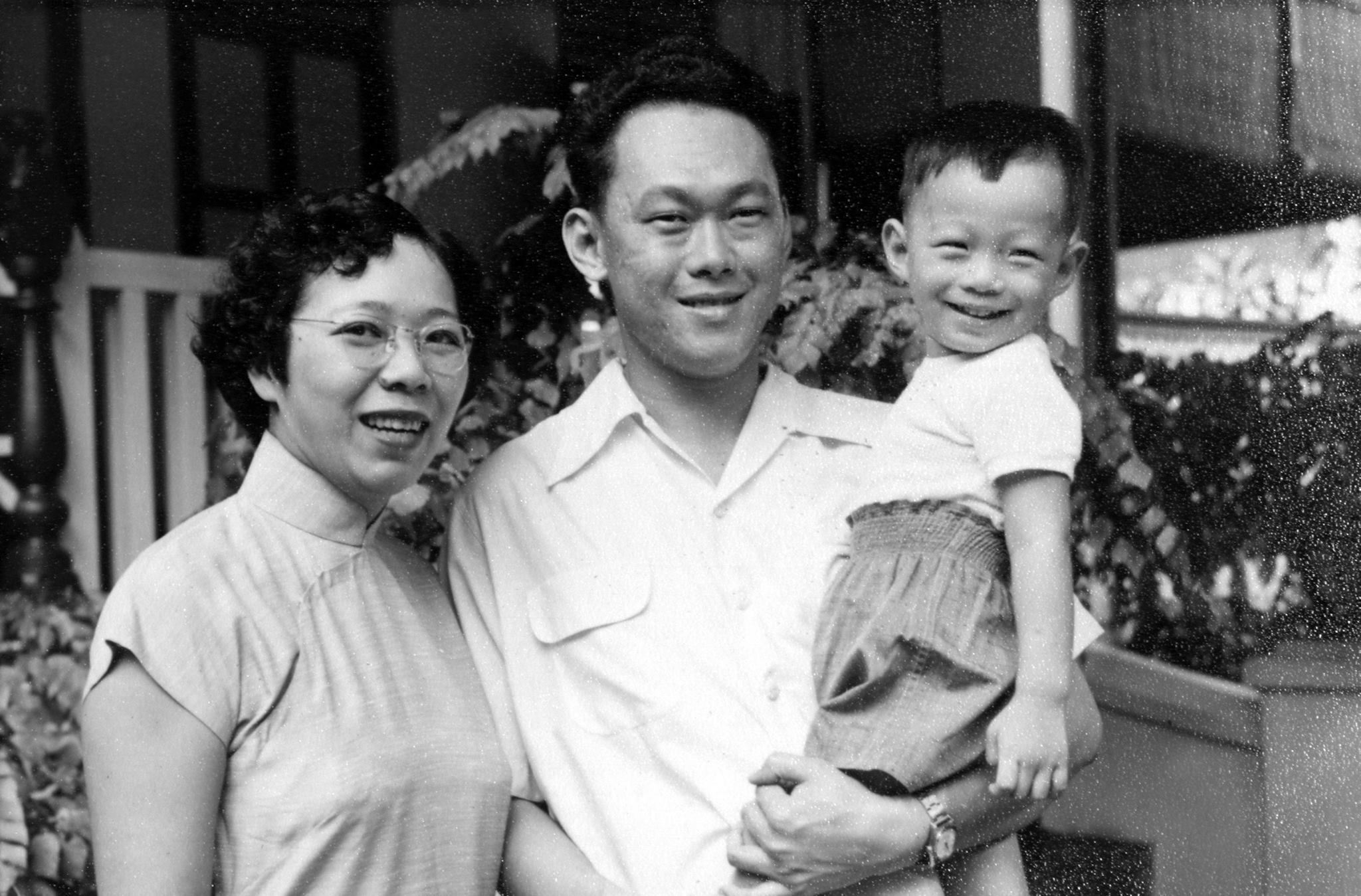

Top image: Lee Hsien Loong/Facebook

Hands up if you are among those who’ve always perceived Kwa Geok Choo as Lee Kuan Yew’s wife, and know nothing else beyond that. Some of you might not even know her full name and simply recognise her as Mrs Lee Kuan Yew.

Unfortunately, I was one of them. And I’m abashed to find out that an upcoming play about Madam Kwa by veteran playwright Ovidia Yu is precisely designed to overturn this perception.

Who can blame us, though? The founding prime minister’s legacy has overshadowed our nation’s history and politics so it’s nearly impossible not to draw associations of those around him to the man himself. Including his own wife.

But it’s 2022, and Singapore should stop identifying her as just Mrs Lee Kuan Yew or just the mother of our current PM, Ovidia told me.

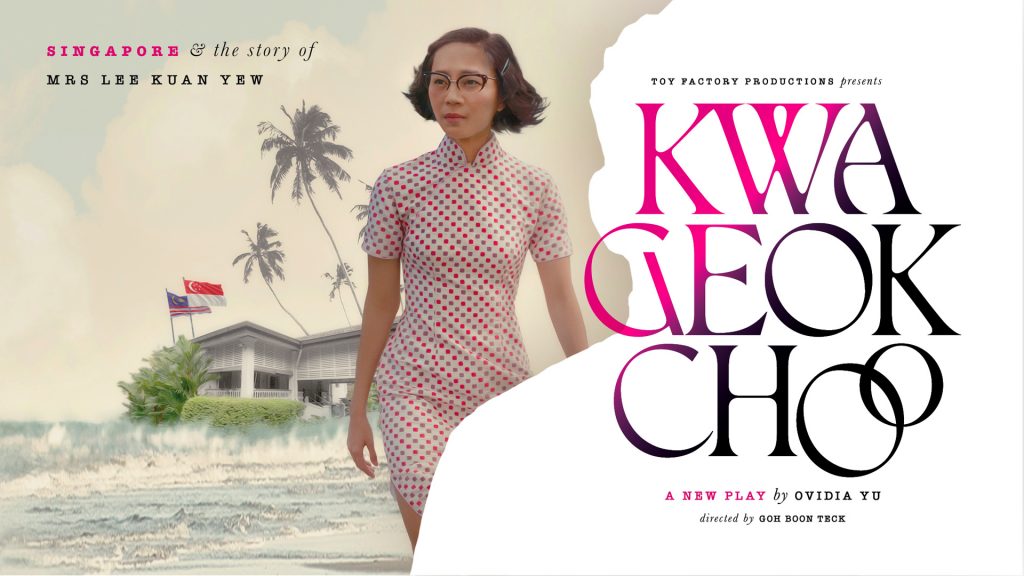

Madam Kwa is a woman in her own right. That’s what Ovidia, 61, wants to convey in Toy Factory’s stage production simply (and appropriately) called Kwa Geok Choo: Singapore and The Story of Mrs Lee Kuan Yew, which will kick off on July 8 at the Victoria Theatre.

The Madam Who Loomed Large in the Shadows

You could say writing about Kwa now is providence. In light of a recent parliamentary debate, a chance to explore her life and re-interpreting her identity beyond her association with the founding PM arrived timely.

In April, MPs debated plans to make Singapore a fairer and more inclusive society for women by proposing (totally reasonable) ideas such as equal opportunities in the workplace, recognition and support for caregivers, and protection against violence.

The jury is still out on Singaporeans’ reactions to the White Paper on Singapore Women’s Development. My colleague Nicole, for instance, pointed out how there were categories of women neglected in the debate, and more can be done to empower them.

But let us recall that the conversation over fairer treatment for the fairer sex started with the Women’s Charter—in which Madam Kwa was involved, never mind that she wasn’t a politician.

“Our society is still built on the assumption that women are the social, political, and economic inferiors of men. This myth has been made the excuse for the exploitation of female labour,” she declared in her sole political speech during the 1959 general elections, arguing the case for equal pay for females decades before its prominent position in cultural conversations today.

A few years following the speech, when Singapore split from Malaysia, Madam Kwa was the brainchild behind securing our water supply with our neighbour up north through the drafting of an agreement. Despite never having a role in public office, she certainly had a hand in some significant, progressive accomplishments.

A Woman Beyond Her Time

Back to Ovidia. When others in the artistic circle knew she was writing the script for Kwa Geok Choo, fellow playwright Ng Yi-Sheng quipped to her: “I hope you portray her as a Disney villainess.”

Not because Madam Kwa was malevolent or notorious like Imelda Marcos. Ng was alluding to her tendency to go against the social norms and challenge the system back then. She studied at Raffles Institution at a time when no girls studied there. She later practised law at a time when there were few female lawyers.

And, of course, she fought for women to have the right to own property and divorce their husbands. These are actions and issues we take for granted today but unheard of for women in the 1950s.

“For her to draft and back the Women’s Charter was as shocking as Ho Ching backing gay rights and decriminalisation of 377A today,” Ovidia says, illustrating the scale of Madam Kwa’s revolutionary and anti-establishment disposition.

Within the system, she went as far as she could go for a woman at the time. And then broke through to go even further, Ovidia adds.

Why Kwa Geok Choo?

At this point, you might ask: Why profile Kwa Geok Choo in a theatrical format? Government sceptics might even question if this is an attempt by the establishment to glorify the PM’s own mother. Is this the last hurrah for what could possibly be Lee Hsien Loong’s final term as PM before he steps down for his successor?

The impetus to profile Madam Kwa didn’t originally come from Ovidia. She did so after Goh Boon Teck — the Chief Artistic Director of Toy Factory — approached her last year with his vision of a show that has been in his mind for more than a decade: paying tribute to a remarkable woman whose actions and influence are responsible for directing the currents and tides that continue to shape lives in Singapore.

As a writer who mostly tells murder and mystery stories, writing a play about a semi-political figure didn’t feel intuitive. But that didn’t stop her.

“With an idea like this, you don’t pass on it. There’s a fantastic subject with so much depth and relevance, more so when you have a group with the time and energy,” she said.

Coincidentally, Ovidia and her mother studied at the Methodist Girls’ School, the same school as Madam Kwa. She learnt in school that Kwa is an influential figure—not just by virtue of her status as Lee Kuan Yew’s wife but also how she too could grow up and do good in society.

While theatre fanatics will recognise that this production won’t be the first to depict the founding father’s partner, Kwa Geok Choo is the first that takes the spotlight away from Lee Kuan Yew and explores the human side of a Singaporean political spouse.

Despite potential concerns, she didn’t feel stressed focusing on this historically significant figure. Curiosity didn’t kill the cat; it drove Ovidia to be part of the play. “It was more like finding out what your mother or grandmother was really like, apart from being the old woman who told you to do your homework,” she said.

“Going further into the past and catching glimpses of her [Madam Kwa] as a playful little girl or romantic young lady, you realise how much work she put into just surviving.”

And the confidence Ovidia has is probably an echo of what was in Madam Kwa when asked if she thinks she is the best playwright to portray the Kwa narrative.

“I’m the most suitable playwright to write my version of the Kwa Geok Choo story,” she asserted.

The Genesis of the Play

It’s astonishing that given the causes Madam Kwa fought for, her achievements, and that she was, inevitably, the spouse of the most powerful man in the land, there’s little about her on public records. Ovidia found it difficult to uncover details of Kwa from the National Archives, in contrast with other men like Goh Chok Tong and the two PM Lees.

In fact, she revealed that most information came from A Hakka Woman’s Singapore Stories, written by Kwa’s daughter Lee Wei Ling, and those who knew Kwa personally—especially those who studied at MGS.

Evidently, Madam Kwa had been rendered a side character all this while. This theatrical production is a deliberate attempt to put her firmly front and centre as the main character in her own story.

Putting Madam Kwa in the forefront meant that the lead actress portraying her is central to the production. Actress Tan Rui Shan, 30, who auditioned and later got the role, didn’t make a good first impression on Ovidia and the production team—she arrived dressed in casual street clothes and left half a sandwich on the table after failing to chomp through lunch.

But what came after during the first table read left them and a tearful producer immersed in the words.

“Just like Kwa, she gave the impression that she’s girlish but strong, or she wouldn’t be able to handle this barrage of words I’m throwing at her. Until it’s time for her to step up, she’s there in the background watching,” Ovidia said.

The ability to conserve one’s strength and recognise the right moment to unleash it is a superpower both Kwa and Rui Shan share. And it’s this attribute that touched the team, similar to how Kwa’s life story plays a role in moving the hearts of Singaporeans.

Can We Ever Move Beyond ‘Mrs LKY’?

Even as Ovidia’s play tries to change our impression of Madam Kwa, the question remains whether we can perceive her as the woman deserving of her own recognition instead of knowing her as the current PM’s mother.

Just to be clear, this play is not meant to be a faithful and accurate portrayal of Madam Kwa. Instead, this is Ovidia’s interpretation of who she thinks the lady is. Those who eventually watch the show will discover that all of us can have the agency to make a change, even with constraints beyond our control.

This should be an inspiration. Look at Kwa—the causes she fought for were considered idealistic at a point in time. As history has shown, it’s possible to push boundaries.

It’s this sheer determination in Kwa that should inspire us to see women in our lives differently after watching this play — that they deserve recognition for their own achievements, and not necessarily in association with other men in their lives. Even if these other men run Singapore.