Top image: Wikimedia Commons

An insurrection seems to be an archaic notion from yore, a time when public beheadings were Monday matinées. And yet, just a year ago, a mob of Trump supporters managed to violently attack and briefly seize the US Capitol building in a dramatic attempt to overturn a presidential election. Pipe bombs and Molotov cocktails were found.

The former US president called the insurrectionists “patriots”. The current US president has a different but befitting term for them: “Terrorists”.

It’s impossible to imagine those same shenanigans replicated here in Singapore, a place of heightened security, muted rebellion and compliant citizens. But what we’re taking away from here: acts fuelled by extremist ideologies these days go beyond typical stereotypes of militant Islamism.

The face of terror has surpassed keffiyehs and turbans; they now don ironic meme shirts about 4Chan and Pepe the Frog.

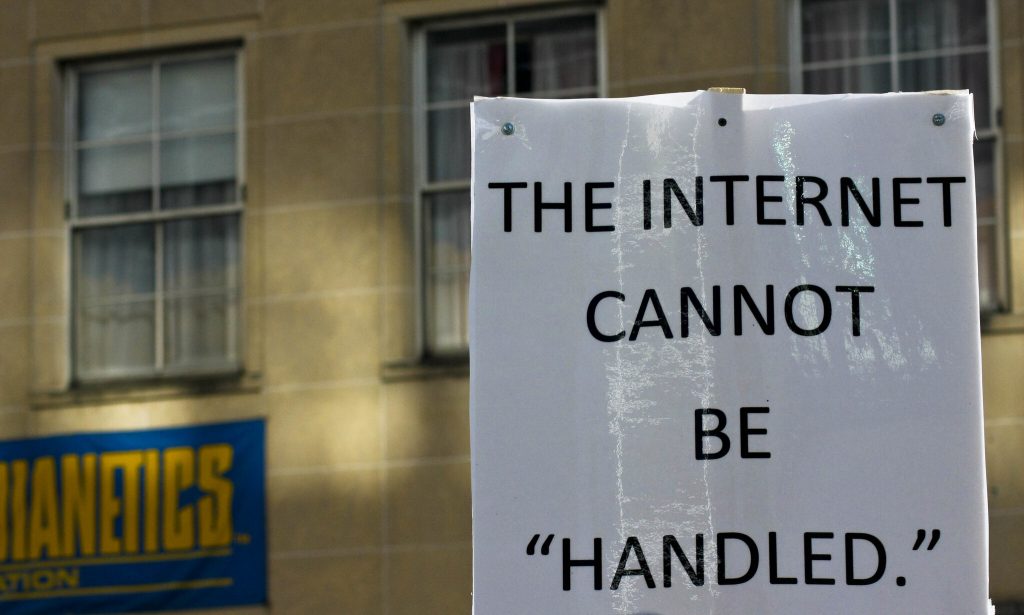

Hate in the Internet Age

The Alt-Right is best described as “Not Your Father’s Hate Group”, which fits the whole white-supremacy-for-the-internet-age thing they’ve got going on.

In lieu of swastika tattoos, white hoods and Nazi memorabilia, the movement focuses on provocative ideologies, caustic rationalism and calculated bigotry. Fuelled by far-right conservatism and amplified by way of the internet, the group believes that (white) civilisation and liberty is under threat by political correctness, social justice and the media at large.

Precisely because they’re more present online, the spread of alt-right ideals (anti-feminism, anti-immigration, anti-multiculturalism) is far more pervasive and global compared to previous forms of conservative agendas. They guise acts of hate as acts of freedom, and are really good at hiding behind the veil of internet trolling, pranking and provocation. It’s half “I hate minorities”, half “here for the lulz”.

Again, it’s hard to imagine US-centric extremist ideologies taking root here, but the threat posed by the Alt-Right is very real. White nationalist violence in 21st century America exploded during Trump’s presidency, so much so that it’s become a bigger form of domestic terrorism than Islamist extremism post-9/11. QAnon — a cultish far-right conspiracy theory movement with millions of followers — constitutes a national security threat in the US, as proven by the Capitol insurrection.

Do we, then, need to start treating agenda-driven internet trolling as national security threats too? That question was answered in December 2020, when a 16-year-old Singaporean was detained for planning to attack two mosques after getting deeply influenced by far-right ideologies online.

You can’t just turn radical overnight. This is a secondary school kid, who should be worried about puberty, grades and emo phases. How virulent can misinformation, conspiracy theories and alt-rightisms be for this youth to launch a terror plan filled with Carousell shopping, Telegram searching, and Google Maps recon by himself?

Genuine Stupidity, Or Legitimate Victims?

But before we throw every conspiracy theory believer under the tin hat umbrella, could they, perhaps, be victims too? Though it’s easier to assume that such individuals are just incapable of parsing what seems to be common logic, studies have shown that even reasonable-seeming people can often be totally irrational: once impressions are formed, even when disproved, can be incredible perseverent. Once an idea has taken hold of the brain, it’s almost impossible to eradicate, as Inception puts forth.

In the case of alt-rights and self-radicalised individuals in Singapore, not all of them had sought extremist ideas, to begin with. One former national serviceman, then arrested at the age of 19, was revealed to have first been exposed to extremist content back in secondary school. While watching videos related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, he came across ISIS-related videos. The continued exposure to ISIS propaganda eventually led to his radicalisation.

In fact, other self-radicalised cases reported in Singapore these few years have all had an online element to them. Just as it is overseas, high levels of social media use have played a major role in self-radicalisation.

A former alt-right filmmaker based in London recounted how his (misguided) anger towards Muslims was fueled largely in part by social media platforms such as YouTube.

He started off watching videos from mainstream media, but as the algorithm caught on with his preferences, it began to suggest more extreme videos involving radical personalities to him, all of whom served to further skew his perception of the world.

Just like in the movie, the inception — ideas implanted within the subconscious when the brain is unable to trace the genesis — transforms into a concept that’s accepted and taken on by the brain itself. Without realising, just doom-scrolling through social media can become a means of brainwashing and the subsequent descent can be so subtle that individuals wholeheartedly believe the misinformation they’re seeing is the truth.

We can’t outlaw algorithms, but there needs to be conscious awareness that online communities facilitate echo chambers. Part of what led to the aforementioned NSF’s extreme views was that his questionable internet browsing continued, even when relatives and friends noticed signs of his radicalisation. What of the other radicalised Singaporeans who found friends online that encouraged their way of thinking?

If anything, the anti-vaccine movement in Singapore is a prime current example of how in times of fear and anxiety, the pervasive feeling of powerlessness drives even more people to seek out conspiracy theories. Any misinformation that helps to direct negative emotions becomes psychologically comforting, it makes people feel as though they’re in control. And once they’ve latched onto misinformation, they become victims to their very human flaws.

Weaponised Irony

You don’t have to go far or that far back in time to find misinformation and conspiracy theories taking root within local communities. Anti-vaccine groups on Telegram remain very active and very vocal — especially after our last jaunt into the anti-vaxxerverse.

If tens of thousands of people could be rallied into thinking Covid vaccines are designed to murder people, it’s not a stretch to believe that malicious parties are already spreading misinformation to jeopardise the efficacy and credibility of response measures by authorities.

Not that we’re saying all government measures are perfect, but there’s a difference between constructive criticism and believing that they’re injecting microchips into people. As cognitive scientists Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber once said: A mouse bent on confirming its belief that there are no cats around would soon be dinner.

Disinformation campaigns across all forms of extremist propaganda are nothing new, of course, but there’s a tinge of nuance to be found in the discord peddled by far-righters. The tool they’ve managed to master is weaponised irony — pushing the boundaries of internet humour to hyperbolic, edgelord-ian extremes. Did you know that milk became a some kind of symbol of white supremacy?

The effect: confusing you into dismissing something that’s genuinely racist, misogynistic and bigoted as just a meme. Irony is used to spread the message while, at the same time, deflecting criticism.

“To the untrained eye, extreme right memes are politically incorrect or edgy satire, not potential terrorist content,” writes associate professor Viveca S. Greene in her article about Alt-Right memes.

“However, their specialised in-jokes and jargon, which often reference seemingly innocuous pop culture items (e.g. cartoons, films, video games), are often uploaded with the intention of ‘rolling off brazen racism’ as ‘half-joking’”.

The role of edgy rightist memes can’t be understated. Brenton Tarrant, the Christchurch killer, included a series of internet jokes into his manifesto. Lines such as “Fortnite taught me to be a killer and to floss the corpses of my enemies” and the Navy SEAL copypasta made it into a document that was written before he killed 51 people at mosques in New Zealand.

Of course, blaming memes for terrorist acts is just as dumb as blaming video games for gun violence. But it goes to show that very few of us — especially those who aren’t extremely online — truly understand the new type of disinformation ecosystem that can turn people into national security threats.

In case it isn’t clear by now, there is a critical need to comprehend internet culture and how it can be exploited for extremist views and actions.

Violence IRL

So to the initial question: Can and should we regard misinformation as a form of terrorism? Can we really regard thoughts and ideas as non-violent anymore?

The answer’s already out there, whether we like it or not, and it’s much closer to home than any of us are comfortable with.

Over in America, we’ve seen how conspiracy theories and misinformation could be wielded to weaponize alt-righters into committing acts of violence.

Here? Much dog-whistling has fanned the flames of racism — no doubt providing the mood music for incentivised individuals, such as the man who attacked an Indian woman seen with her mask down (to exercise) by delivering a kick to her chest.

In a separate incident, another man publicly insulted an Indian family, even accusing them of spreading the virus. What was in common? These attacks occurred just days after the Delta variant (then, still referred to as the ‘Indian variant’) was detected in Singapore, fuelled by festering xenophobia and amplified by online sentiments.

With biases amplified within echo chambers across social media, the foreseeable future is but a vicious cycle of reciprocal violence between Singapore’s brand of supremacist far-right and religious extremism, spiralling and feeding into each other.

The internet is run by algorithms that dictate the Next Content To Consume based on our own preferences, a digital mirror of our own subconscious sentiment towards the world. It’s getting harder to discern what’s our original thought and what’s something we read somewhere. But before letting online misinformation spill into real life as violent events, it’d be good to wise up to the psychological elements that hold sway over our deep-seated beliefs.