In collaboration with CHAT, Thriving in Transition is a series dealing with how we make meaning of our individual experiences and emotions through finding solace in the support of others, no matter how daunting it can be to reach out. After exploring what loneliness looks like among Singaporean youth and the spectrum of suicidal thoughts, we examine the perils of self-diagnosing mental health disorders via social media.

All images: Stephanie Lee for Rice Media

If there’s one upside to the pandemic, it’s this: we’ve felt obliged, culturally, to make further efforts to destigmatize mental illness. Though it’s still cloaked in a degree of shame and taboo, the importance of mental wellness has taken centre stage on account of the profound isolation and disconnection from social distancing.

It’s as though we’ve raised our consciousness to a more holistic view of health. I’ve experienced this first-hand at work — our readers are keen to understand and feel understood. Since I joined RICE in 2021, I’ve noticed that my colleagues have progressively grown emboldened to share mental health stories: from toxic work practices to burnout, suicidality to bipolar disorder.

Perhaps the willingness to share experiences comes from our generational bond with social media. This collective reckoning with mental health is compounded by the need to connect during 2021’s sporadic restrictions.

Although we’ve made strides to raise our consciousness on a holistic picture of health— and the various environmental factors which contribute to it—I can’t help but wonder if this newfound awareness will be short-lived.

Because mental health content on social media, for the most part, lacks nuance.

How we find information—and where we go to find it—has warped our ability to assess its veracity. The proliferation of misinformation, or incomplete information, has the potential to walk back the strides we’ve taken towards raising our mental health consciousness.

So, the question to explore is this: How can we continue to destigmatise mental illness with the gravity it deserves on social media?

Gen Z’s Mental Health Literacy Is Inspiring (And Kind Of Radical), But Is It Effective?

Gen Z has consistently polled as an unhappy cohort. Their coming of age period has included wars, the birth of social media, and the pandemic. Overall, Gen Z is grappling with novel issues that have no historical precedent. In a global survey by McKinsey, Gen Z reported “lower levels of emotional and social well-being than older generations” and a significantly less positive outlook on life.

This feels incongruous with their relative mental health literacy. Online, Gen Z is ready and willing to confront their demons. Look no further than TikTok, where there’s open discourse on the lived experience of mental illness. Under hashtags such as #ADHD and #bipolar, TikTok users contribute millions of videos discussing symptoms, diagnosis, and social stigma. Whereas prior generations might not have been able to articulate the difference between depression and anxiety, for example, Gen Z can likely differentiate them as unique experiences.

Dr Jayne Ho a consultant at IMH’s Early Psychosis Intervention Program and CHAT, encounters this fluency on a regular basis with her young patients: “It’s increasingly common that I’ll have patients come in who have identified areas of distress in their lives, and cross-referenced their struggles on social media to investigate the reason behind their discomfort.”

But it’s on social media where the finer intricacies of mental health issues may be lacking. On platforms where snappiness and entertainment value sit high on the algorithm, there may not be enough room for nuance in content. The growing environmental distress of a young generation, paired with the immediacy and immersive allure of social media, holds the potential to worsen complex issues, not alleviate them.

Dr Jayne further remarks that psychiatric symptoms—for example, mood fluctuation, inattentiveness, and significant tiredness—are common in the general population. She notes that “at some point we have all had some kind of psychiatric symptom, but experiencing one symptom does not necessarily mean one has a psychiatric disorder.”

She links this back to her clinical intake process, where occasionally, she meets young patients who have come in for a consultation with a preconceived notion of what they are suffering from. Which leads me to a novel problem that Gen Z is currently facing: self-diagnosis.

Building Community Can Help Break The Stigma

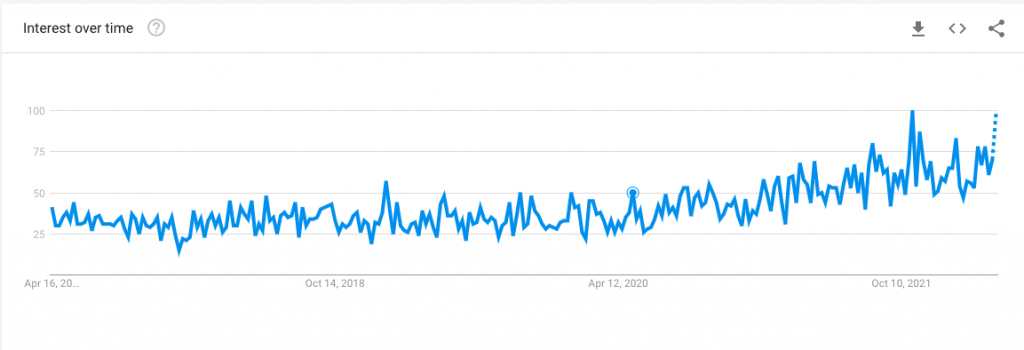

When it comes to self-diagnosis, an apt phenomenon to explore is the explosion of interest in ADHD. Since the pandemic started, Google trends show an uptick in searches for the neurodevelopmental disorder starting in April 2020, which peaked in October 2021 and it continues to climb in popularity. Media outlets, from CNA to Vogue Singapore, have covered the proliferation of the disorder extensively.

But… why are we suddenly interested in ADHD, specifically in adult ADHD? Perhaps it’s due to increased visibility on social media. Informal knowledge sharing in private support groups, such as Unlocking ADHD, has helped raise awareness of the lived experience. These spaces are a great comfort to those who feel isolated due to their illness; particularly in Singapore, where discourse on mental illness still has room for improvement.

There’s another line of inquiry to explore here—the double-edged sword of how the presentation of a disorder can gloss over the nuance while spreading awareness. Knowledge-sharing groups, though helpful to those who have sought an expert opinion, are an incomplete source of information. The diagnostic process for any disease — mental health-related or not — is holistic and requires an expert analysis of the various factors which contribute to the patient’s overall wellness.

By nature, social media removes context and nuance. It’s a byproduct of the built-in ephemerality and the volatility of the algorithms, which want to keep you engaged, not necessarily informed.

Here’s where it gets tricky.

Where is the Nuance?

Increased access to information has not increased our ability to decipher good information. In a 2021 study on Singaporean’s media habits conducted by Edelman, only 18 percent of respondents were found to have good information hygiene. Broadly speaking, the survey takes ‘good’ information hygiene as such: does the respondent spread misinformation, verify their sources, and avoid echo chambers?

In the traditional publishing world, an authoritative source is qualified by expertise. Editors of all kinds are in place to ensure that given information is factually correct. But there’s no such formality on social media, where users present their subjective views as ‘facts’.

Take for example popular ADHD creator @peterhyphen. With over 400k followers on TikTok, he often instructs his followers to “look out for these symptoms” before listing some common phenomena.

Though he speaks with gusto and his following is vast, he’s no expert.

Peter is simply a person with ADHD disseminating seemingly informative content on TikTok in a manner that appeals to a modern audience. When the algorithm picks up more and more videos like these and delivers them to a user, how is the user supposed to discern the good from the bad information? After all, as Dr Jayne mentioned, sometimes the symptoms described are general and non-specific. Brain fog, depression, and daydreaming are not always symptoms of ADHD.

Of course, feeling seen and understood is paramount. However, although perfectly well-intentioned, sharing one’s own subjective experience is unlikely to alleviate someone else’s suffering from mental health issues. Personal anecdotes cannot supplant complete information.

What’s equally important as feeling seen and understood, is receiving quality care through the expert opinion of a professional.

The Life-Changing Magic Of Professional Help

In my own mental health journey, I’ve learned how to decipher good from bad information through trial by error. As a teenager, I was terminally online. There was no TikTok, but I trawled through the underbelly of Tumblr. I submerged myself in the diary-posting cult of other terminally online teens, who also felt alienated from the world around them and misunderstood by their peers.

I trusted the people who spoke my language; my followers and friends on Tumblr, who shared my interests and experiences. At some point, I fell into a dark rabbit-hole, full of depressing diary-posting. Sparing you the gory details, I absorbed a bleak worldview that life would always be drained of colour. Subconsciously, I mimicked the behaviours I read in these diary posts.

I found bad information from a supposedly authoritative source.

Backed slowly into a corner of my own making, the adults in my life noticed the withdrawal and encouraged me to consult a professional. That first meeting with the professional clarified things for me. I could name my feelings (the symptoms) and trace them to a larger problem (the diagnosis).

Like Goldilocks, I only found the right professional after trying out many different kinds. Some were too cerebral, others were too esoteric. When I found the right one, a lightbulb went off in my head. She described the diagnosis I had received years prior as something that I have not something that I am.

Reframing my struggles as such gave me back some agency I lost along the way. I’d fallen down further internet rabbit holes and begun to think of myself as a disordered person, rather than a person with a manageable disorder. Now, when I come across something online that speaks to me or raises an alarm, I’ll sit on it for a while and bring it up with the professional in our next session.

In this way, the professional is able to remedy the incomplete or incorrect information. Developing a close relationship with a professional who sees me regularly—and has the full picture of who I am with plenty of context—allows her to assess my condition with nuance. Something that self-diagnosing via social media could never do.

And because of that, my mental wellness has increased dramatically.

Keeping The End Goal In Mind

The mental health content on social media is rooted in categorisation: symptoms, labels, disorders, diagnoses.

Part of what makes this content authoritative and appealing is that it provides a shortcut to understanding oneself. And certainly, labels are a useful way to help us make sense of certain hurdles and specific behaviours. For adolescents, self-categorisation is a way to bond with the group. It just so happens that nowadays, finding one’s tribe happens online.

But I think the danger of finding one’s tribe through this kind of content is existential. Ultimately, we want to make sense of ourselves. That comes from meaning and purpose, which are not inherent but are in fact gifts we create for ourselves. There’s no shortcut to contentment, and one’s whole life experience can’t possibly be neatly categorised or defined by a disorder or a diagnosis.

Dr Jayne concurs: “It’s natural to seek simple answers to our problems. Labels and diagnoses give a sense of control, which is an answer of sorts. They offer a path to a solution, but in and of themselves, diagnoses are not the solution. This is why a self-diagnosis without expertise simply won’t fix a problem: the path you’re taking might be the wrong one.”

“Sometimes we have recall bias when we hear about psychiatric symptoms that ring true. That’s when you look back on your past experience with a lens that’s not entirely objective, mining for clues of this idea you’ve encountered. ”

A compelling point she goes on to make is that many of our perceived flaws are reflective of the messiness in the human condition—not always a malignant symptom of a larger problem.

“Sometimes we are impulsive, depressed, sad, and anxious. That’s okay. These dispositions can be part of one’s character. For example, some people are naturally more anxious than others. They don’t necessarily have an anxiety disorder.”

With that in mind, we return to the original question. How can we intercept or reorient the spread of incomplete information, while fostering dialogue in an effort to destigmatise mental illness?

Dr Jayne shared that parasocial relationships are a driving force here: “We put a lot of faith in content creators, applying their own experience to our lives because we feel connected to them. Mental health content creators can help remedy incomplete information by reminding the audience their experiences are their own, but can’t replace professional help.”

And of course, it’s not entirely up to creators to add nuance to the wider conversation.

“There’s an onus on the viewer to have some discretion and evaluate their sources. We should always be suspicious of bite-sized, digestible content that proclaims to explain a complex mental health disorder.”

Ultimately, though this new mental health literacy has created a knowledge gap, it seems (for now) to have a net positive impact overall. Dr Jayne observes that “more young people are feeling empowered to come in and talk with us. Being open to having a conversation about their mental health gives us the opportunity to steer them in the right direction”.

In my own mental health journey, I’ve felt empowered by the conscious semantic shift from “I am my disorder” to “I have a disorder”. It’s allowed me to accept myself as a flawed human being with a smorgasbord of emotions. And I wouldn’t have found this power on my own, or on social media, without an expert.