In ‘Singaporeans Abroad’, we share with you the stories of locals who—thanks to living in a globalised world—have found success in different corners of the globe, whether financially, romantically, or for the pure joy of adventure. We’ve recently heard from Kenneth, the Singaporean head chef at the world’s best restaurant, and Vino, a Singaporean living through Sri Lanka’s protests.

Now, we bring you Mathias Heng, a conflict photographer and photojournalist covering war zones, social issues, and humanitarian crises for the past 37 years. Recently, he witnessed the war in Ukraine with his own eyes.

Growing up in Singapore, most kids around me aspired to become doctors, lawyers, or bankers. I never really knew what I wanted to be, but I knew it wasn’t that.

With time, I slowly figured out that I wanted to work in a creative field, and by the time I was 14, I decided to enrol myself into Boys Town and take up a course in graphics, production, and photography.

ADVERTISEMENT

Once I graduated, there was only really one pathway for photographers in Singapore at the time, which was working in the commercial field. While I did try taking up jobs in fashion for a while, overall, it was hard to stray from the industry.

It was so hard to be a photographer that out of the 12 students in the creative course I took, I was the only one who pursued photography full time. I remember how many people would ask me: “how are you going to make money doing photography?” But I’ve always believed that you have to follow your heart and do what you want, or you will regret it later.

After a few years of working in fashion and commercial photography, I noticed myself growing increasingly dissatisfied with my career. I didn’t feel like I was tapping into my maximum potential, and there was so much outside of my comfort zone that I wanted to explore.

I was always interested in humanity and looking at the human experience across the globe. I wanted to use photography to be a journalist, but there were no journalism schools in Singapore at the time—my only option was to self-teach and self-fund my projects.

Eventually, I started using the money I was earning from my commercial jobs to fund my side projects in conflict photography across the region.

Beijing and the start of my career

One of my first breakthroughs came about in Beijing during the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre. I was there by chance for another job and happened to be there when students started pouring out onto the streets to protest. I did manage to take some photos, but I remember how everything was crushed very quickly. The army came in and started shooting in the middle of the night, and by the following day, everything was cleared.

After that experience in China, I knew this was the field I wanted to dedicate my life to. It is difficult, especially when you witness brutal events that impact you in a magnitude of ways over time—but they are historical and need to be documented.

As a society, we should not let history repeat itself. I hope that photos may help us remember why.

Regionally, I started growing my portfolio in conflict photography, but in Singapore, my work was not recognised. I remember taking my photos to editors and constantly being turned away. I was always told there was no appetite in Singapore for confrontational photography.

Instead, these editors were looking for photographers to take pictures of ministers cutting a ribbon or shaking a hand, so I never got hired.

At this point, I was in my mid-twenties, and I thought to myself, what do I have to lose? Why am I trying to prove myself here, and struggling, when I can take a chance abroad?

So I took the leap and moved to London, where I worked for a couple of years, and from there, I ended up in Australia for a while.

ADVERTISEMENT

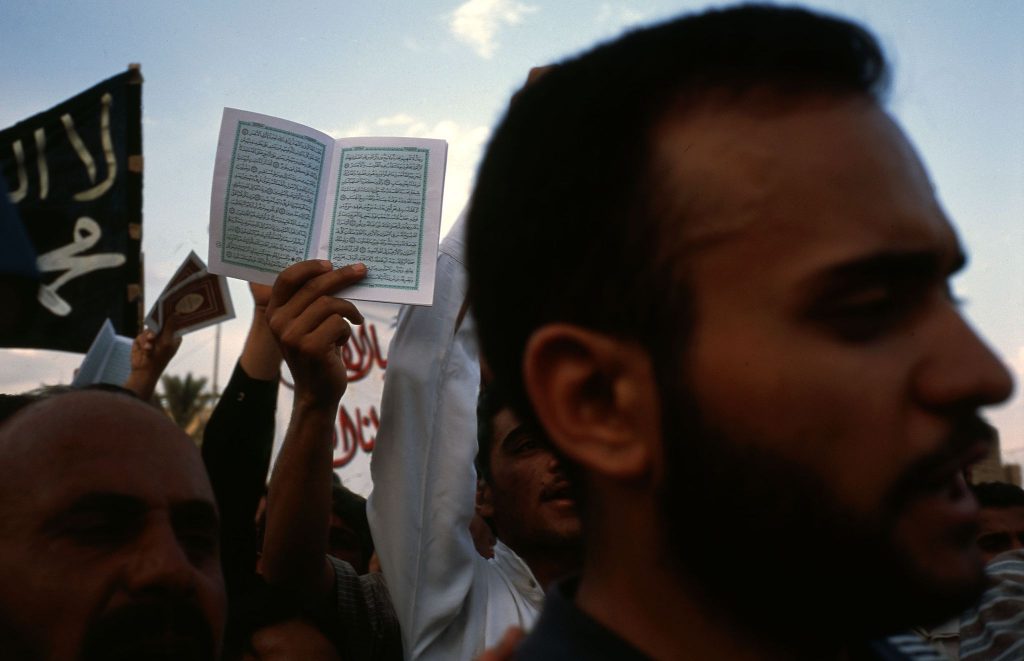

Iraq

At the start, when moving abroad, there will be obstacles. Especially if you go to a country with a different language, you will need to give yourself time to acclimatise, get used to the local culture, and pick up a few words. Integrating can be challenging, but it is not impossible.

The more you put yourself outside of your comfort zone, the more you will grow as an individual. Travelling and moving gave me so much exposure to the world and opened up my horizons. And professionally, it changed everything.

I finally started covering massive global conflicts and getting commissioned to travel worldwide. With this, however, came exposure to a lot more danger.

In Iraq, I came extremely close to dying—twice.

ADVERTISEMENT

We were on a train from Baghdad to Basra when our train suddenly stopped. After over half an hour, there were still no signs that we would be leaving soon. At this point, many villagers started coming out to look into the train. It was supposed to be a discreet, express train to our destination for security reasons, but crowds around us started growing bigger and bigger.

At the time, any foreigners (and of any colour) in the country were assumed to be Americans— the enemy. So three men came up with rocket-propelled grenades pointed at us. When I saw the weapons, I shouted “RPG,” and everyone took cover. The correspondent I was with jumped out of the train carriage and managed to talk the men out of their plan, and they eventually left.

At this point, it would have been unsafe to continue our journey on the same train, so we found a vehicle to travel by instead. That night, when we got to Basra, fights broke out, and we got to work taking photos.

Everything was peaceful the following day, and you could see life going on, so we went to the local markets.

There, two men came up to me in greeted me in Arabic, saying “assalamualaikum,” to which I politely replied with “mualaikumsalam.”

The guy in front of me shook my hand and looked me up and down. Then, he started talking to the man behind me in Arabic, which I couldn’t understand.

I later found out from my correspondent, who understood Arabic, that the man who shook my hand said, “What are you waiting for? Shoot him!” to the man behind me.

“I can’t shoot him. Look, the British troops are on patrol,” he responded.

The moment he said that, the correspondent said, “Mathias, we have to go.”

“No, we need to stay to take photos,” I replied, unknowing.

Then, his voice became stern, and he said: “We have to go right now.”

I realised something was wrong, and we walked away to find shelter. There, he told me everything that had just transpired.

If it weren’t for the soldiers patrolling the area, I think I would have died right there.

Ukraine

Most recently, I have been doing a lot of work in Ukraine.

One day, I was on the frontlines when the conflict grew intense. There was a lot of artillery, shelling, and firing, so we left to take cover.

As we were walking, we could hear the whizzing sound of a drone, but we couldn’t see it. The sound of its blades grew louder, and eventually, we spotted a drone flying far above our heads.

The moment it went out of sight, the Russians started firing in our direction, and we started running while shells were landing 80 meters from us. Eventually, we found a safe spot and hid there.

When I tell people these stories, especially about my recent time in Ukraine, they often think I’m crazy for putting myself in such dangerous situations. But for me, the more I’m faced with these situations, the more I value life. And it sounds contradictory—if you love your life, why would you put yourself in a position that risks it?

What it means, to me, is to be more intentional with my life. I’ve seen enough, and I’ve realised that material wealth means nothing to me. I don’t care about watches or branded clothes. What matters is that I’m healthy and can do what I love, because I have realised how fortunate I am to have that as an option.

Life on the move

Now, I’ve decided to be based out of Paris. There are a lot of photo agencies there, and generally, their culture is more photo-oriented than most others. As much as I’d like to be based out of Singapore, there isn’t a market here. People are interested in photos, but a different kind. Despite this, I still make it a point to visit Singapore very often, especially whenever I travel to Asia.

After years of doing this job, I still enjoy travelling. And while that doesn’t tire me, what becomes difficult is the sense of no belonging that comes with always being on the move.

I often stop and ask myself, where do I come from? Where is my sense of belonging? But I remind myself that it’s only normal to feel lost, especially when you are in a career like mine.

I don’t intend to slow down for now because I still feel that fire in me. I’m dedicated, and I’m always looking to get more impactful pictures that are strong and reach out to people.

I want to help tell the story of humankind, and I don’t want to do it for me but for the people out there, the audience. Not everybody gets to go to a war or conflict zone, so I can at least hope that my photos send the message of what it is like.

Without proof, it’s hard for people to understand the extent of what is going on in the world. That is why journalism and photography are such essential tools of communication. They offer eyes to people who would be blind otherwise.