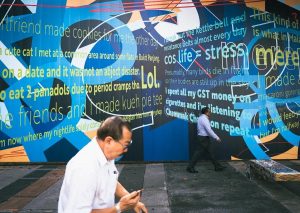

Top Image: Jones Lim

“I’ve never heard of a group of guys talking about in-depth emotional intricacies. I think it boils down to the rootedness of our friend group,” Lim Hao quips. “It’s not that we shun that emotional side of us. Our friend group transcends sharing our feelings—we’re just stable, you know.”

Separated only by a screen, 24-year-old Hao, a final-year engineering undergraduate, answers matter-of-factly the questions I’m asking about the quality of our friendship. His reaction, though, was consistent with the abrasively candid personality I knew him for in our eleven-year friendship.

ADVERTISEMENT

Hao and I have spent a better part of those eleven years sharing the same circle of close friends—all men, a distinction that informs the exploration of this story. Seven of us are final—year undergraduates, most of whom are in engineering or business.

Our distinctively adolescent dynamic, a cultural remnant of the all-boys secondary school we grew up in, has been built on regular recreational football, dissonantly juvenile jokes, and competitive mahjong sessions.

“Should I be worried? Was I the drama?”

In one of those mahjong sessions, on a balmy Saturday evening, Felicia—it was the first time we were being introduced to our friend’s girlfriend—asked, almost off-handedly, whether we’ve ever shared our feelings with each other.

An ensuing awkward silence from the four of us that were present, scattered around the mahjong table, revealed it all—platonic emotional intimacy was a difficult topic to broach for our friend group.

Perhaps, this all-boys club was doomed to be a dysfunctional time warp, one that transports us back to a place of unfeelingness when we’re together.

Still, that our friend group was beyond predictable platonic emotional intimacy was immensely jarring—it was puzzling that such intimacy was uncharted territory for friends I’ve known close to half my life.

Should I be worried? Was I the drama?

“It’s the same for every other all-men friend group”

It’s not lost on me that the first time Hao openly shared his emotions with me was in a formal context of an interview. Despite the initial awkwardness, I wanted to know if we both secretly desired more platonic emotional intimacy, held back only by self-imposed restraints.

Hao thinks that if our friend group were emotionally open, it would change how he viewed the dynamics of the friend group. “It would be kind of weird,” he posits. “Even the person that is most comfortable with sharing his feelings does so only through private Instagram posts.”

Soon, Hao’s steady stream of candid responses slowed to a crawl, replaced with cautiously measured ones—it bordered uncomfortably close to PR speak.

“I think that the fact that we don’t share our feelings is not unique.”

“Yes, I know we haven’t been emotionally intimate with each other, but I believe we are well-equipped to do so. I’m sure we use the emotional training we gained from friendships outside of this friend group for this friend group.”

Since we don’t have the experience of being emotionally intimate with each other, it remains to be seen whether our friend group can respond appropriately in times of emotional distress.

“I think that the fact that we don’t share our feelings is not unique,” Hao explained. “It’s the same for every other all-men friend group. It’s not explicit, but we do pick up on signals. For us, I don’t think it’s problematic. At least not now, but I guess only time will tell,” he speculates, almost shrugging at the implication.

The barometers of a healthy male friendship

31-year-old Benjamin, an openly gay man working in Singapore’s finance industry, has a platonic emotional intimacy with his friend that I envy—a model of what I think healthy male friendships might look like. Evidently, emotionally intimate friendships among men do exist.

ADVERTISEMENT

He’s known his closest male friend, Glenn, for close to half of his life—something we both shared in common. “We’ve been in the same secondary school, same JC class, same army camp, and same university. In fact, when we started working, it was the same building,” he says with a laugh.

For Benjamin, a serendipitous string of milestones ensured their lives were closely intertwined. Still, if my friend group is anything to go by, I am also cognizant that knowing someone for a long time does not guarantee platonic emotional intimacy.

I just wanted my friends to know that they could always rely on me for emotional support.

“It’s not something that we’ve explicitly said, but I’ll definitely share with Glenn good news and bad news,” Benjamin slowly recalls, “I’ll also talk to him about life updates—job interviews, bad days. I’ll go to my friend for emotional support. We’ve been through tough stuff together, and I see him as a pillar of emotional support.”

“Emotional intimacy is important. For me, I want to share my vulnerabilities; to be emotionally intimate with my friends. You want your true friends to know who you truly are and to be comfortable with you—not someone that is putting on an act—and vice versa. It’s a two-way street,” Benjamin carefully replies, sporting a cheerful tone.

Perhaps, over the years, I had become increasingly sensitive to the peculiar possibility that I was comfortable with a filtered version of my closest friends—one stripped of the emotional vulnerability and messiness, all uncomfortably sterile for eleven-year-old friendships.

At the heart of it, I just wanted my friends to know that they could always rely on me for emotional support. And I wanted to find out whether they would do the same for me.

Destigmatising platonic emotional intimacy

The closest that my friends and I have gotten to an ounce of vulnerability is during a Secret Santa gift exchange two years ago. Even then, we were all so awkward with sharing the thought we put behind the presents that we gave up after five minutes.

I was robbed of the opportunity to tell my friend that I bought him a pair of socks because he complained that his feet were cold back where he lived in Scotland, and we had talked about it before. It was a practical decision limited by budget.

Predictably, we quickly retreated to something more comfortable—selecting which side of the mahjong table to sit at. If you can’t already tell, the mahjong table was our emotional crutch.

ADVERTISEMENT

Still, as I soon learned, destigmatising platonic emotional intimacy among men is not impossible, although seemingly difficult. Men do not have to be the emotional blackholes that society thinks they should be—uncaring, unflinching, and unperturbed with something as irrational as emotions.

“We are unfamiliar with expressing emotions, so we don’t.”

It’s something Mr Hafeez Hassan, a movement coach, choreographer, and dancer, took pains to explain to me as he delivers astute observations about masculinity in a calm and serene tone, displaying a familiarity with the nuances of how ideals of masculinity can enter ‘toxic’ territory.

Hafeez is the founder of The Brothers Circle, a support group dedicated to helping Singaporean men unlearn toxic patterns of masculinity. The end goal is to get them comfortable in their own skin and with platonic emotional intimacy.

“As a kid, I was exposed to many Hollywood movies. I saw what a man should look and think like. I thought being a man was about being a hero—you need to suffer and endure pain at any cost,” Hafeez explains, alluding to his first ideas about masculinity.

He narrows in on the rush of embarrassment men have tricked themselves into feeling whenever they want to express emotions and to be emotionally intimate with each other.

“It’s called ‘shame’. As a kid, you feel ashamed whenever you want to express your emotions. And most times, it starts from home and extends to school. If it’s not school, then it’s national service, Hafeez adds. “We are unfamiliar with expressing emotions, so we don’t. It affects how men connect.”

Indeed, traditional ideals of masculinity, based on stoicism, self-sacrifice, and aggression, pressure men into thinking that their struggles are burdensome to their friends.

For fear of ridicule and shame, some men keep their emotions under lock and key, even when they’re with their closest friends. And eventually, through sheer force of socialisation, we stop being comfortable with sharing our feelings entirely.

Essentially, we’re stopping ourselves from reaching platonic emotional intimacy.

Creating a comfortable version of masculinity

That’s where The Brothers Circle think they can help. The group focuses on meditative movement and reflection amongst men, presenting itself as an active solution to combating the phenomenon of men being socially uncomfortable with their feelings here in Singapore.

In a picture Hafeez shared with me, a group of seven men lay sprawled across a wooden floor, arranged in a circle—this is typical of a session at The Brothers Circle. With some cajoling, Hafeez asks them to express their version of an ideal man on a piece of paper in front of each of them. It could be a drawing or a text—anything they wanted. They were limited only by their imagination.

Visualising their ideal masculinity will be important for later; they’re about to express their personal visions through Hafeez’s guided movement and gestures.

“This back and forth with movement helps them in their unique journey of masculinity. We learn what we’re putting into our bodies. That’s where the trauma grows,” Hafeez thoughtfully explains.

“Soon, we realise that our ideas of masculinity are shaped by the first men we come into contact with—our fathers and grandfathers. Some participants realise that they share the same traits with their fathers.”

“We cannot put toxic ideas about masculinity into our bodies.”

While the search for authentic masculinity must be constantly revised, the sessions at The Brothers Circle demonstrate that one principle holds true regardless: men don’t need to buy into toxic masculinity ideals—one based on the ideas of stoicism, self-sacrifice, and aggression.

Indeed, creating a version of masculinity that we are comfortable with means that we do not have to buy into the traditional idea that men somehow have to “go it alone”.

Hopefully, this increases the willingness to share their vulnerabilities and emotions with their friends—the first step to platonic emotional intimacy.

Hafeez carefully distils years of exploration of masculinity into a few short seconds.

“There is no absolute masculinity because masculinity is ultimately not gender-based. It is more of an energy or characteristic. It’s not about the heavy lifting or the suffering. It’s about what we can do to be of service. We cannot put toxic ideas about masculinity into our bodies.”

The problem of emotional intimacy between men

Hafeez cites years of pent-up frustrations from being a minority with little to no emotional support as the main contributors to his father’s aggression. “It was a very tough period growing up with my father. He used to train me and my older brother in Silat at the playground downstairs. He would use the training session to abuse us physically.”

“When I was eight years old, my father would ask me to pick a fight with a random person. He would pick a fight with a random person as well.”

“If I ask men where they want to be held so they can feel good, most of them would say their dicks.”

It’s a stark example of how, with few available emotional outlets, we risk expressing ourselves in unhealthy ways. In the case of Hafeez’s father: aggression. In fact, The Brothers Circle is a brainchild borne from these traumatic experiences.

Crucially, close friendships void of platonic emotional intimacy mean one fewer outlet men can turn to for help. In the worst-case scenario, detecting suicide risk factors, such as distressing life events and changes in mood and behaviour, become less likely. Especially when a lower willingness to share means that fewer people are privy to their friends’ struggles.

According to Samaritans of Singapore, males accounted for more than 70% of all suicides in 2020. Perhaps, this is an important reason why men are more likely than women to commit suicide in Singapore—a global phenomenon replicated on our shores.

Furthermore, in heterosexual relationships, behind a well-adjusted straight adult man is almost always a woman who is wholly responsible for being an emotional punching bag—a form of emotional labour that often goes unseen, unheard, and under-appreciated.

To love courageously

“If I ask men where they want to be held so they can feel good, most of them would say their dicks,” Hafeez answers half-jokingly, “But if I ask them again, they would say their necks or their chests.”

Their reply is symbolic of men’s attitude towards platonic emotional intimacy—initial dismissiveness gives way to meaningful conversations about unmet emotional needs.

“We lack touch and intimacy because everything has been sexualised. Like I said, That’s where the trauma grows,” Hafeez shares. To him, platonic touch and emotional intimacy are worth having those awkward conversations over.

Perhaps, this is a conversation with my friends that is long overdue.

Disentangling our own ideas of masculinity with society’s vague prescriptions is messy work. But the work is worth it.

Hafeez, once again, emphasises the value of intimacy among friends. “Everyone needs to connect through touch or communication, especially because we live in modern society. Love courageously. Don’t be afraid to love and to show love towards your friends. Reach out for help when you need to. It is as simple as talking through your problems with your most trusted friends.”

Disentangling our own ideas of masculinity with society’s vague prescriptions is messy work. But, the work is worth it, especially when it leads to a point when you can be sure that your friends now are indeed friends for life.

“I cherish you guys. To me, that’s more than love. It’s about treating every moment that we spend with each other preciously. Honestly, I see us still being friends in the next 30 years,” Hao concludes at the end of our interview, his first moment of vulnerability in a long time.

I make a mental note to start an important conversation, one that I consider crucial to the next 30 years of our friendship, the next time my friends and I meet for emotional-crutch mahjong. Awkward or not, uncomfortable or otherwise. Stay tuned.