Having first arrived in the early 1990s, the Japanese community in Ho Chi Minh city today is one of the largest and longest-standing expat groups, giving way to an entire neighbourhood of sushi joints, whisky bars, closed-door massage parlours and sex-starved salarymen.

It’s the same every afternoon. In the wet season at least. A ghostly mountain range of clouds draws up over the horizon as a wall of water comes sweeping over the flatlands of Vietnam’s southern delta. And then it hits. The daily storm rolls into town and Saigon begins to roar with the sounds of thunder and water and a billion overflowing drainpipes.

As the modern office blocks of District 1 begin draining themselves of bodies at the end of the working day, as leather shoes and stilettos are bagged and sealed and swapped for flip-flops, the city’s workforce transforms into an armada of motorbikes that cut and carve through the flooded downtown streets.

In the neighbourhood around Le Thanh Ton Street—the lively thoroughfare that dissects District 1 from east to west—Friday night has come early. Cold fluorescent street lamps flicker to life, neon spills down onto the wet concrete, lightning slams down all around, and a cluster of souls take shelter in a nearby bar.

This is Little Tokyo—or “the ghetto” as it is often known—the hub of Saigon’s Japanese community, a microcosm of Nippon culture packed into a maze of narrow alleyways and concrete passages strung with makeshift lights and thick tangled cabling.

5.30pm

Powers is the perfect Japanese dive bar. Offering a mishmash of world-class whisky, ice-cold beer, darkened corners and grungy skate culture, with Japanese surf movies on the TV and a red haze of cigarette smoke looming over the backbar, there’s nothing else like it in Ho Chi Minh City.

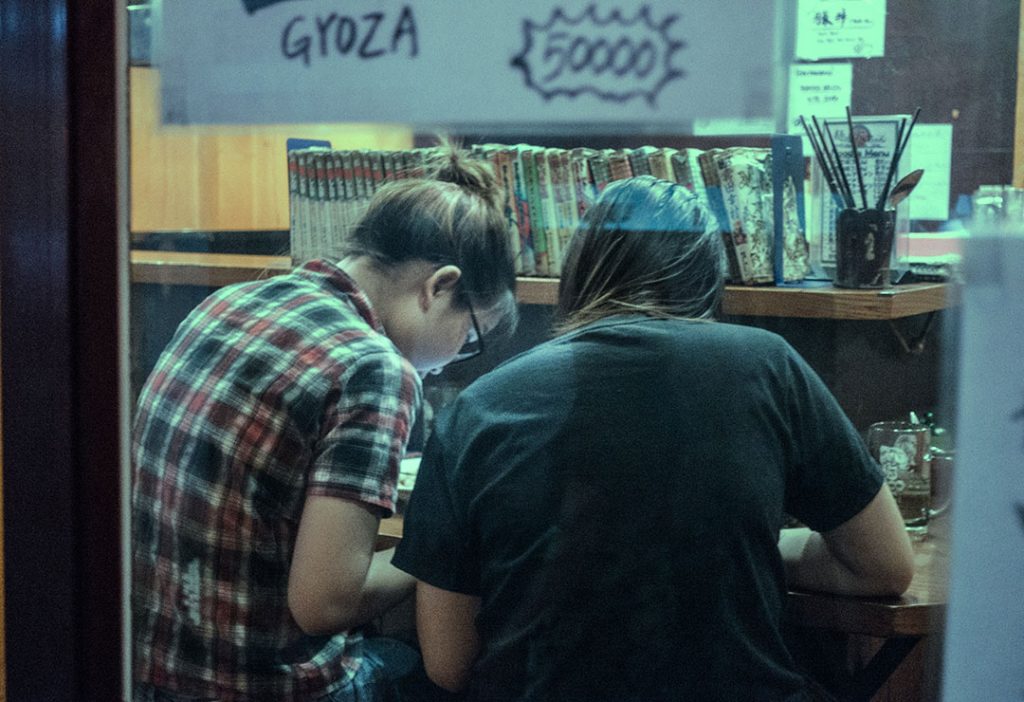

Between the manga figurines and polished ashtrays lined up on the countertop sits a selection of imported (and technically illegal) Tenga male masturbation aids. A table of female tourists giggle at the novelty of it all while downing late-afternoon bottles of backpacker-friendly local lager. The rest of the Powers crowd are on the draft Sapporo. Served in tall glasses and topped with a thick icy head, it’s a happy hour essential in Japansville.

The rain eases to a patter and the ghetto’s inhabitants reemerge. The concrete alleyways glisten underfoot, freshly polished and slick with colour. Twirling a transparent umbrella and teetering on six-inch stilettos, with knockout-red lips and a smartphone clutched in her free hand, a Vietnamese spa worker steps out onto the concrete to wave and giggle and the passing menfolk. “Massage sir?”

You’ll hear that a lot come nightfall. It seems innocent enough to stay on the right side of sleazy. Many of the spas, like this one, are bright and welcoming, with open fronts, smart menus and clearly displayed prices. Prostitution is illegal in Vietnam, and while “extras” may well be on offer, full sex is rarely offered or expected. The flesh-fuelled hedonism of Thailand, for example, does not (yet) sit well with Vietnamese culture.

7.30pm

For the hungry and the thirsty, like Golden Gai of Tokyo itself, the ghetto is best experienced with a crawl; a slow and steady exploration of the neighbourhood’s numerous establishments, each tinier, busier and tastier than the last. Torisho izakaya is filled to bursting point already. Elbow-to-elbow along the counter, the salarymen of Saigon are replacing the stress and monotony of the nine-to-five slog with beer, banter, and freshly-grilled meat skewers.

The rain has stopped. In the darkness outside, way up above the roofline, the ghostly concrete skeleton of a stalled office block project looks down over the scene; another victim in the scattered remains of Vietnam’s property bubble. At ground level, however, the ghetto is booming.

New bars and restaurants are springing up each month, each week, each day. As construction workers continue kitting out the latest sushi bar across the street from Torisho, groups of girls in tiny dresses and heavy makeup scurry back and forth between the members-only closed-door establishments to pour expensive sake and exchange sweet smiles with the CEOs and business-class elite.

9.30pm

When it comes to Japan’s national dish, the area around Le Thanh Ton Street is home to some of the best sushi and sashimi restaurants you’re likely to find in Vietnam. Robata Dining An, a split-level counter and private booth restaurant out on the main road, is one of them.

To an upbeat soundtrack of V Pop, K Pop and J Pop, Robata’s expert sushi chef dissects shimmering slabs of tuna and salmon in the open kitchen as his guests gaze on. Between the bleary-eyed solo diners, with laptop cases propped against their polished shoes, sits a young Vietnamese couple on a date, chatting and laughing and grazing over an endless parade of small plates.

As post-war Vietnam began opening up to foreign investment from the late 1980s onwards, Japan was one of the first countries to move in. For the Vietnamese born in the 1990s, the “9X Generation” as they are known, raised on translated Japanese comic books, TV cartoons and Doraemon, it’s a culture they’re eager to aspire to, and to recreate.

11pm

Vietnam’s nighttime curfews are slowly falling away, yet things still tend to die down as midnight approaches. Young revellers head for the glitzy all-night clubs while the rest of the city heads to bed. As an area once officially off-limits to Saigon’s civilian police (it was once home to the officer’s residential quarters for the nearby naval base), Saigon’s “Tokyo Town” continues to remain isolated in many ways from the laws and customs of the world beyond its high walls and narrow streets. Despite being nicknamed “the ghetto”, and despite the somewhat seedier businesses based here, it’s a surprisingly safe and hassle-free area to explore (as a man or a woman).

With its own private security detachment and CCTV network, things rarely get out of hand. As in Japan, drunken antics (and other anti-social acts) are best played out behind closed doors.

At 11pm, most of the spas are still open—the girls now in even more revealing skirts and dresses, their waves and giggles evermore brazen and alluring—and the thoughts of the thirsty have turned from malt and hops to grain and rye. The whisky menu at The Blues Bar beckons. Around its cosy bar, with BB King sizzling on the sound system, find familiar and not-so-familiar tipples from both sides of the Pacific.

Two American English teachers chat idly about work and travel as a trio of Osaka natives take stools beside them. The teachers shuffle up one seat to make space and after a couple of rounds of Maker’s Mark and 12-year Yamazaki, everybody is everybody’s drinking buddy. Then the guitars come out.

1am

As a late-night, post-binge, after-party diner, Matsuzakaya is about as good as it gets. It also serves the best chicken katsu curry you ever tasted. Streaked with cooking grease and open until the small hours, Matsuzakaya (and its sister establishment on the opposite corner, a ramen bar) is a favourite spot among night-workers, screen-frazzled students, and, naturally, boozed up hangover dodgers.

Along with cigarette smoke and the general reek of alcohol, expect the cooking smells of this place to still be clinging to you the next day, but oh, it’s so worth it.

2am

It’s quiet outside now. A few scooters buzz past in the alleyway, the click-clack of stilettos returning home, rubbish collectors and market vendors heading out to take advantage of the cool air.

Most places are closed and shuttered, yet there’s still a hint of life and light seeping out from the upper floors and from behind closed doors. For that one last can of cheap lager, the you’ll regret in the morning, find the harsh cold lights of the 24-hour Family Mart and its depressingly sterile seating area. At less than a dollar a can, you’re free to continue drinking here until sunrise, although a bottle of Japan’s favourite sports hydration drink (the oh-so-Japanese “Pocari Sweat”), would be the wiser choice. As they say, nothing good happens after 2am, so please, just go home.