Top Image: Marcelo Leal/Unsplash

All names have been changed

“A calling, sure, but you don’t have to sacrifice your life for a calling, right? Even priests get paid more than this, and it’s a calling too,” a rather exasperated 25-year-old Isobel tells me over Zoom. As a House Officer (HO), Isobel has heard her fair share of criticism aimed at junior doctors, calling them entitled ‘snowflakes’ and entirely ill-equipped for handling the rigours of practising medicine.

However, nothing grates more on the ears of junior doctors when senior doctors justify the absurdly early call times, unreasonable patients, never-ending administrative tasks, and exhausting overnight calls with this ‘higher calling’ to serve.

These pressures on junior doctors are only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the realities of being a doctor in public healthcare. For all its perceived prestige, the career prospects and future for doctors in Singapore are often bleak and unbelievably draining.

Bright-eyed and bushy-tailed

There are various reasons why someone goes into the profession of medicine. Some achieved the grades during their A-levels, and, coupled with a strong interest in science and an opportunity to serve; medicine made the most sense.

For Alex, a 28-year-old Medical Officer (MO) who works in the Emergency Department, the lure of becoming a doctor was to be on the cutting edge of medical science. “I thought that there was a lot of fame and honour to do medicine. That’s why I got in,” Alex admits.

It’s a common sentiment shared by many, and for Isobel, she went into medicine for its stability and how it was “termed to be lucrative at one point in time”. “At the same time, I couldn’t imagine myself doing anything else. I felt like medicine was the right path, and it seemed like a good career option,” continues Isobel.

Along with these reasons, pursuing a career in medicine often stems from an altruistic place with a strong desire to make a difference in the lives of others.

“I wanted to do something meaningful. I liked interacting with people, patient communication, and helping people when they are in a vulnerable place,” shares first-year HO Cristina. Besides these reasons, the motivation to become a doctor ran a little deeper as Cristina had a brush with the profession when she fell sick and had to be hospitalised for one to two years.

“I could see how being a doctor could have so much value to a patient’s life. I wanted to be in a position where my patient could trust me as I did with my doctor,” adds Cristina.

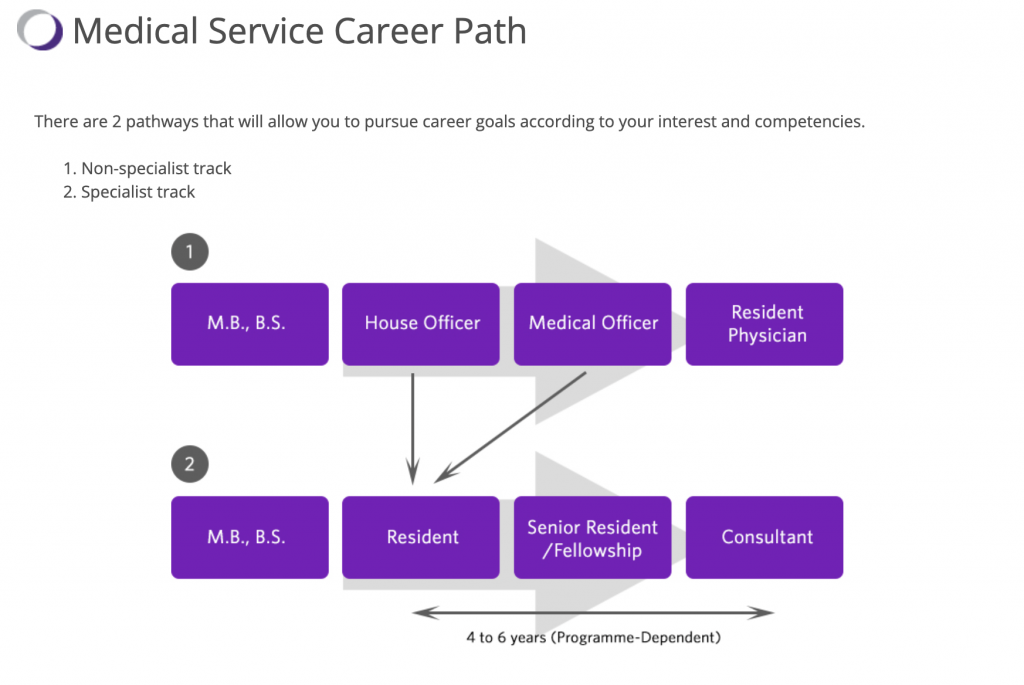

Fresh out of medical school, these young doctors will embark on their House Officer training. According to the Ministry of Health Holding’s (MOHH) website, it is a “period of clinical apprenticeship that aims to equip a new medical graduate with the basic skills of clinical practice” and typically lasts a year.

Here doctors would have a provisional licence where they would need to be supervised when they perform their clinical duties.

A discipline where lives are on the line is no doubt gruelling. Still, the physical and mental toll on doctors, even beyond their Housemanship, speaks to some of the significant inadequacies and even egregious practices in Singapore’s public healthcare system. These flaws require a serious re-examination of the public healthcare system and more profound, helpful intervention.

A large, disappointing disconnect

With all these noble ambitions of changing the world and giving back to the community, the reality of being a doctor in public healthcare proves to be more arduous and demanding than any of these doctors ever imagined.

“I think we all came here because we love medicine and serving patients. That’s why we entered the profession in the first place. But, the reality of the whole situation is that much of our work is not centred around patient interaction or patient care,” says Cristina.

This sense of disconnect is perhaps most keenly felt by Miranda, a first-year MO who went into medicine to make a difference but instead found herself dealing with an inordinate amount of paperwork.

“I was thinking to myself, I don’t want a desk job, but honestly, this is quite a desk job,” Miranda says plainly. “We are bogged down by electronic documentation most of the time. We are usually at the computer typing notes for a patient, doing summaries like memos, ordering medicine; there’s quite a lot of stuff to do,” continues Miranda.

“I heard that it would be hard, but I just didn’t know how bad it would be when I came along and how imperfect the system is,” says Miranda, “It’s like a desk job—but with people dying”.

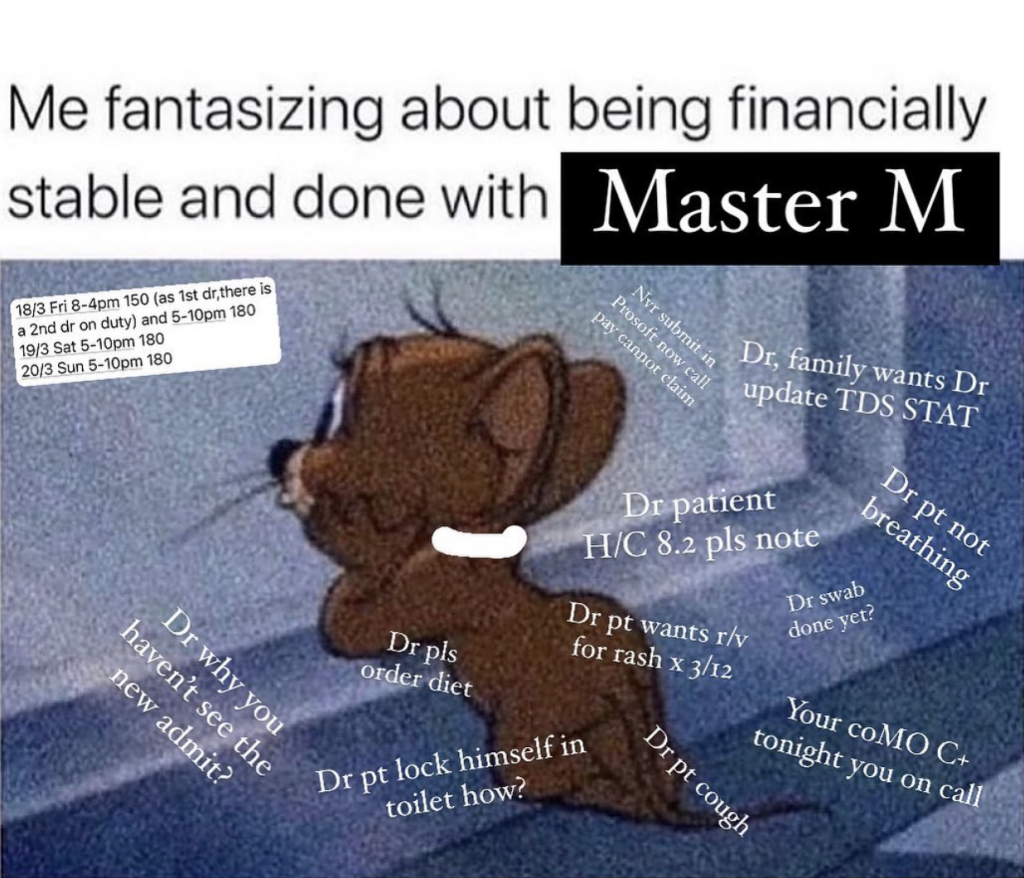

This disenchantment most doctors go through is best documented by the founder of the Instagram account @Updatemeprn. The account doles out snappy and pointed memes about life in the public healthcare system that are funny and call attention to the sobering truth about being a doctor in Singapore.

“Believe it or not, I truly did get into medicine to help. As I progressed through the system, I realised keeping someone warm in their current state requires you to set yourself on fire,” says @Updatemeprn, a statement that cuts as deep as their memes do.

“There are too many rigid and outdated ideologies cemented in place reinforced by a vicious cycle of schadenfreude,” reveals @Updatemeprn.

Of course, this is not to say that junior doctors are not committed to their patients. Given that junior doctors carry out so much of the legwork, they are just as dedicated to their patients as senior doctors, if not more. Still, it begs the question of why so many junior doctors are burnt out and have poor mental health.

The rude awakening of being on-call

The many popular portrayals of medicine in popular media have skewed our perception of the profession. No thanks to Grey’s Anatomy’s McDreamy and other highly sensationalised medical shows with a dose of melodrama.

These portrayals paint a select image of what it is like in the field. Yes, there is some truth to these depictions, but it often leaves out the intricacies of public healthcare and the more unsavoury parts of being a doctor.

Perhaps, one of the most strenuous and least understood parts of being a junior doctor are the overnight calls. They typically start from 5pm and don’t include the typical day duties the doctor has to perform from 5am to 6am that morning, which runs till about 12pm the next day.

That amounts to about 30 hours at work—barring any rest times. As the on-call doctor, depending on the medical institution, you’ll usually be overseeing anywhere between 100 to 200 patients, a stark contrast to day duties, where you only see about 40 patients.

The pressure further mounts from the flood of calls and texts from colleagues, letting you know which tests to follow up on and which scans to do. Calls are overwhelmingly stressful; @Updatemeprn, a doctor, also describes how they are in “pure survival mode on call just to make sure no one dies”.

“24 to 28 hours in, I honestly cannot give a fuck anymore about the ‘Why’, I just want to finish the job, go home and collapse in bed,” says @Updatemeprn.

As an eager young House Officer, Cristina thought she could handle the intensity of calls. She describes how she was on a high for her first few calls, fuelled by the excitement of learning and the initial joy of being a doctor. It’s a high that came crashing down quickly soon after.

“The fact of the matter is that when you are at your 28th or 29th hour of work, the capacity you have to give is a lot less, which can be quite frustrating. It is unfair to my patients that I’m so tired at work,” relates Cristina.

Isobel describes calls as everything flying at you all at once; whether it is tending to a patient who is haemorrhaging internally, overseeing new emergency admits or ordering a sleeping pill, the work is relentless and seemingly endless.

“I don’t think anyone, including myself, knows the extent of how much energy, or, rather lack of energy you would have overnight, the number of tasks that you have to do, and the level of stress you had to face—and not just from your seniors alone,” reveals Isobel.

The night float

For the mental turmoil that HOs have to go through, they are paid S$200 for weekday calls and S$320 for weekend calls, which only recently increased from S$120 and S$165, respectively. MOs are paid slightly more at S$300 for weekday calls and S$480 for weekend calls.

An increase in call pay is encouraging; however, Cristina maintains that no amount of money will ever be enough for the ordeal of overnight calls.

There have been valiant efforts to improve the system of overnight calls with the implementation of the Night Float system. This is where doctors are split into day and night teams where, instead of working demanding 30-hour days, doctors are allowed to work 12 to 14 hour night shifts for 5 to 7 consecutive nights instead. The Night Float system has been shown to effectively combat doctor burnout and fatigue; it is also shown to improve doctor camaraderie and improve learning for doctors.

In fact, as Miranda shares, it has been implemented in NUH and Ng Teng Foong but was recently scrapped, citing manpower issues, “it’s sad, it was making such good progress, and now it all goes back to square one”.

After all, a longer time spent in the hospital does not necessarily equate to better doctors. As clearly evinced, working such 30 to 36-hour shifts is “absurd and dangerous”, @Updatemeprn asserts that time is a poor metric to gauge a doctor’s ability and progress.

We have made enquiries to MOH regarding junior doctor hours on-call and the administering of the Night Float system and did not receive a response.

A toxic working culture

There needs to be a pecking order in healthcare to ensure that more emergent conditions are escalated to doctors who are more equipped to handle them. However, this hierarchy often contributes to an unhealthy culture perpetuated by senior doctors; as Miranda describes, “there is a bit of perverse glorification of their suffering”.

Senior doctors love to put forth “back in my day” monologues, where they would boast about their worst moments or their worst calls, bragging about working for 40 hours straight and carrying it proudly as a badge of honour.

More than championing unnecessary suffering, there seems to be a spate of bad behaviour by senior doctors. “There are doctors that I’ve met that are really rude and vulgar and almost abusive. They speak to the juniors in a terrible way. I don’t know how they’ve gotten away with it for so many years and still hold senior consultants positions,” shares Cristina.

Gaslighting feedback

Alex recalls his experience with a senior doctor where he felt mentally battered with racial comments thrown around. Unsurprisingly, the incident left him a little undone.

“It was damned if I do, damned if I don’t kind of situation. The senior doctor was micromanaging to the point that I was scared to even go to the restroom,” says Alex. “Even how I manage the patients, she would deem it inappropriate, even though she would do the same thing”.

Alex is not one to shy away from incidents like this, and when he brought it up formally to the hospital, “they said that they would deal with it, but I didn’t get a follow-up,” he shares. “I can either trust that something was done or be sceptical and wonder if it was just hidden from me”. It’s hard to say which is more frustrating, the fact that nothing to our knowledge was done or the lack of transparency on the entire incident.

There is also a culture where it does not feel safe to give feedback, even if it is constructive. “If we were to say something truthful or something honest about a rotation, like ‘I was overworked’ or ‘the culture was toxic’, they will find a way to gaslight us and tell us it’s because we are not good or inefficient, or we can’t manage this amount of workload. Everyone always ends up unhappy”, says Miranda, a matter of factly.

Of course, of all the junior doctors I spoke to, they were also quick to point out there were senior doctors there who cared about their well-being and understood their difficulties as well.

Then again, as Miranda points out, “I guess even if the senior doctors are very nice and helping us on the ground, they’re not speaking up about the problems as much. Then, when toxic traits surface among the seniors, they might just take a more passive stance. It still continues”.

Under-declaring working hours

The Singapore Medical Council (SMC) stipulates that work should not exceed 80 hours per week, including night call hours, to ensure doctors are not overworked. In addition, there should be at least 10 full hours of rest between duty periods and an off day each week.

Furthermore, Post-graduate Year 1 (PGY1) doctors cannot be scheduled for more than 24 hours of continuous active duty managing patients. For those who have completed a 24-hour duty period, their hand-overs to colleagues or other activities (e.g. educational activities) should not take more than an additional six hours.

PGY1 refers to the transition year that prepares newly graduated doctors for Full Medical Registration.

Indeed, there are safeguards in place to ensure proper working hours. Hospitals have to adhere to them even though 24 hours of continuous active management of patients are long and potentially dangerous.

Miranda, however, tells a different story altogether. She speaks of the pressure she has from senior administrators to under-declare their hours. Miranda explains that junior doctors are supposed to log their hours on a platform that will apparently be audited by an external group.

“Let’s say I go to work at 5.45 am or 6.30am, depending on the department,” Miranda explains. “Then, the senior admins will say, you should only log the official starting time, which is 8 am, even if you were there at 6 am.”

Rounds work like this: Rounds start at 8am – when the consultants arrive. Junior doctors usually arrive at least one hour or one and a half-hour earlier to prepare, see the patients, put up the entries, and do all the necessary paperwork before the official start time. Sometimes, junior doctors might have to come in even earlier if their senior doctor on duty wants to round even earlier.

“When we do log our hours accurately, we sometimes have to talk to a senior doctor or a supervisor to explain why we logged these hours,” says Miranda. When the explanation is that she has too much to do or she is covering for someone, it is usually met with a dismissive “you’re not efficient enough”.

“So, it’s us. It’s always our fault,” says Miranda.

It’s unfair, exasperating, and demoralising. After all, logging in hours accurately is a good way to gauge if changes can be made to the allocation of manpower or adjustment to the hours. Not to mention it seemingly erases all the work junior doctors have to do before rounding starts.

Miranda posits there might be some kind of repercussion or a different allocation of resources to this hospital if they are noted for these infringements. “It doesn’t make sense, right,” she asks incredulously, “because if everyone’s working longer hours, shouldn’t they take more steps to help the hospital instead?”.

We have reached out to MOH regarding the under-declaring of work hours for comment but did not receive a reply.

MOPEX Purgatory

After going through their Housemanship, junior doctors become Medical Officers (MOs) and go through a 6-month posting exercise called the Medical Officer Posting Exercise (MOPEX). According to MOHH’s website, “MOs may choose postings which suit their developmental needs and career interest”.

Through these postings, it is the hope that junior doctors can discover their affinity or knack for certain specialities and be emboldened to pursue them. However, the reality of MOPEX is far from enriching or even educational, for some it is a miserable limbo or as @Updatemeprn puts it the “black box of MOPEX” that can only be broken by the switch to the private sector.

For starters, positions in coveted postings are limited and incredibly competitive. MOs very often end up getting postings they don’t want at all; more than that, the reason why some MOs get their postings or not is murky at best.

“There’s no transparency behind their process,” Miranda explains, “I think it’s very highly dependent on connections, if you know people, or if you have a recommendation. Or even sometimes, if there’s a manpower issue, then they will just send you there”.

“I think when we were in med school, we all had this rosy idea that we would all become specialists. But, in reality, there are very few residency slots for the majority of the specialist positions.” To give you an idea, popular specialities like paediatrics, plastics, or orthopaedics, have only one or two slots per year, and there could be hundreds of people that are interested.

The waiting time for these specialities is five to six years and a small proportion go MOs will actually wait to get these positions. In the meantime, these junior doctors will ‘MOPEX’ around at different hospitals and rotations with no career progression, till they get the elusive ‘yes’ from their coveted speciality.

Other MOs who do not want to wait either serve out their bond of five years or break their bond to accelerate the move to the private sector.

We have reached out to MOH for a comment regarding the MOPEX posting system and have not received a reply.

The hollow promise of being a doctor

With all this in mind, it might make the reasons why there was a huge resignation in the public healthcare industry at the end of 2021 and an exodus of doctors from the public healthcare sector to the private sector a little clearer. While Covid-19 was a huge push, we must consider that there were already glaring issues only exacerbated by Covid-19.

While Miranda is still set on being a doctor, the bleak and uncompromising public healthcare system has done a number on her. “Rarely do I feel passionate or inspired. I always feel disappointed and frustrated; those are my two main sentiments. I’m dragging myself through the day, and I’m just getting by,” she says.

Isobel had initially set her sights on obstetrics but discovered that it might be a goal she could never realise. “I don’t know if I can still be an ONG (obstetrician) because it takes a lot of energy, time, and many sacrifices that you wouldn’t understand until you get into the job itself,” Isobel explains. “It is much harder to handle all these things, and it is much harder to get where I thought I wanted to be.”

“I think nobody ever enters medicine thinking that they’re going to go private,” says Cristina. As much as she wants to do her part for her community, a future in public healthcare is just not for her. “More than the money, people switch to private for the work-life balance,” she explains.

“I still want to be a doctor. I still want to care for my patients. It’s just that I feel like this situation that I’m in is not optimal for me to be the best up there that I can be.”