All images by Stephanie Lee for RICE Media.

Don’t you ever wish Singapore was… less hot?

There’s only so much we can do to beat the heat. And for those of us going through it without air-conditioning—aka the very machine leaving us in a never-ending cycle under global warming—it’s just tough.

Sweating is just part and parcel of living in Singapore, even as you sit, completely sedentary, in your room trying to hammer out words (like me). I love air-conditioning as much as the next sweaty guy, but I have bills to pay—and I can’t afford to let it run through the day.

So, when I had an afternoon to talk to Jackson Tan, I arrived drenched, as usual. Jackson is the co-founder and creative director of design agency BLACK, and he’s prepared a walkthrough for his upcoming exhibition Playground of Possibilities.

Playground of Possibilities was specially commissioned for Singapore Design Week 2023 as part of its Bras Basah Bugis design district, which also features exhibitions that reimagine how Singaporeans can learn (School of Tomorrow by Kinetic Singapore) and play (FI&LD by Lekker Architects).

Singapore Design Week’s messaging for the year is ‘Better by Design’, and these three projects display its values through the concepts of inclusivity, sustainability, and innovation.

When it comes to Jackson’s playground, one of its possibilities is a cooler way of living. Let’s say my interest right now is far beyond piqued. Beguiled. Spellbound. Frozen in shock.

I’ve got some questions. But I need to freshen up first.

The Possibilities Beyond

So, uh, Jackson: what’s up with these, uh, “cooler buildings”?

He chuckles. “You know, the funny thing is that I was in Japan in summer, two months ago,” he recalls. “And it actually [felt] hotter than [in] Singapore. I actually appreciate Singapore. It’s not as hot as we think.”

You may tell me to agree to disagree, but I find it hard to believe there are people here who appreciate our country in its balmy glory. Not that I’m pushing back against our beloved island–I just really dislike the weather here.

“We grew up [with the] perception that is Singapore is hot,” he argues. “But Singapore has a lot of shade and foliage, which you don’t get in other cities. I really appreciate it here when I come back.”

I can’t fault Jackson for being optimistic. We’re sitting just across Playground of Possibilities, which forms one of three main keynote exhibitions of Singapore Design Week 2023.

It’s bright, colourful, and interactive—it has questions about progress and innovation that are swiftly answered by quirky new ideas. While it presents itself with an enthusiastic (even childlike) attitude towards progress, you get the feeling it was carved with intention, one that comes from living through the challenges of living in Singapore.

The exhibition, which runs until December 31, lines up a selection of imaginative concepts with Singapore’s social ecosystem in mind, with the hopeful aim of making Singapore more inclusive, accessible, and, yes, cooler.

“This exhibition looks at how Singapore has progressed over the last 20 years,” he explains. “True progress,” he highlights, along with the way Singaporean society is “shaping up” and what “challenges we face” from here.

Playground of Possibilities takes its hand at addressing broader social concerns—housing discomfort for both citizens and migrant workers, sustainable materials for everyday items—but it also makes a point about expanding possibilities beyond the margins.

The exhibition is segmented into four value pillars: Explore, Empathise, Imagine, and Adapt, which also take the form of the Pals of Possibilities mascots, all present and complete with googly eyes for a quick photo-op during your visit.

Its two pillars, Empathise and Adapt, challenge the way we think about how Singapore can be made more accessible for others—from conceptualizing an entire housing estate just for dementia patients to designing new, dignified types of medical prosthetics that are both seamless and stylish.

“Whether it’s the climate crisis, an ageing population, or a labour crunch, how do designers, and the [design] community at large, look at design as a tool?” he poses. “As a way to basically play with possibilities and turn those problems into possibilities.”

The fundamental point of the exhibition is a simple one: problem-solving isn’t just for engineers.

Design in Singapore

One such problem the exhibition addresses through design is our heat. Singapore isn’t a relentless industrial oven, but it does feel like our weather malfunctions—erratic rainstorms in the day, balmy heat at night, and discomfort all around. Singapore’s air-con servicemen are fully booked.

And when they do come around, it feels like the tweaks and maintenance they provide pale against our insurmountable climate.

If Jackson had as many gripes as me, he wouldn’t be here. Playground of Possibilities shows what effective design can do: expand our imagination. Its form as an exhibition is already meant to pave the possibilities in the minds of attendees while also showing how design itself can help make these ideas a livable reality.

That kind of optimism in imagination has been key for Jackson: he is, after all, someone who had been taken under the wings of Dr. Milton Tan, the founding director of DesignSingapore Council (Dsg), as a then-fledgling designer.

“At the time, it was only him—just one person,” he recalls. In 2003, there was yet to be a Dsg building. “And no office!” he emphasises.

“He called me just as I was restarting a studio, which became BLACK.” Jackson’s previous studio, which mainly dealt with advertising work, crashed during the SARS crisis. Back then, he states, design wasn’t taken as seriously as it is today.

“[Design] also has a larger impact on social and cultural, besides economy [and trade],” he elaborates. “So [the launch of Dsg] was a real big shift.” Dr. Tan championed for design’s seat at the table, and “his energy really translated down.” In 2023, Dsg celebrates its 20th anniversary.

“He built this,” Jackson says, looking at the varnished foyer of the DSG building. “He really rooted this.”

Bumps and Cracks

Jackson is solemn as he reflects on his late mentor. I quickly bring the conversation back to the present day—I can’t let the topic of Singapore’s heat go.

Within his patented Playground, he shows me a collage of textured, bulbous green tiles made by bioSEA, a local firm specializing in ecological solutions.

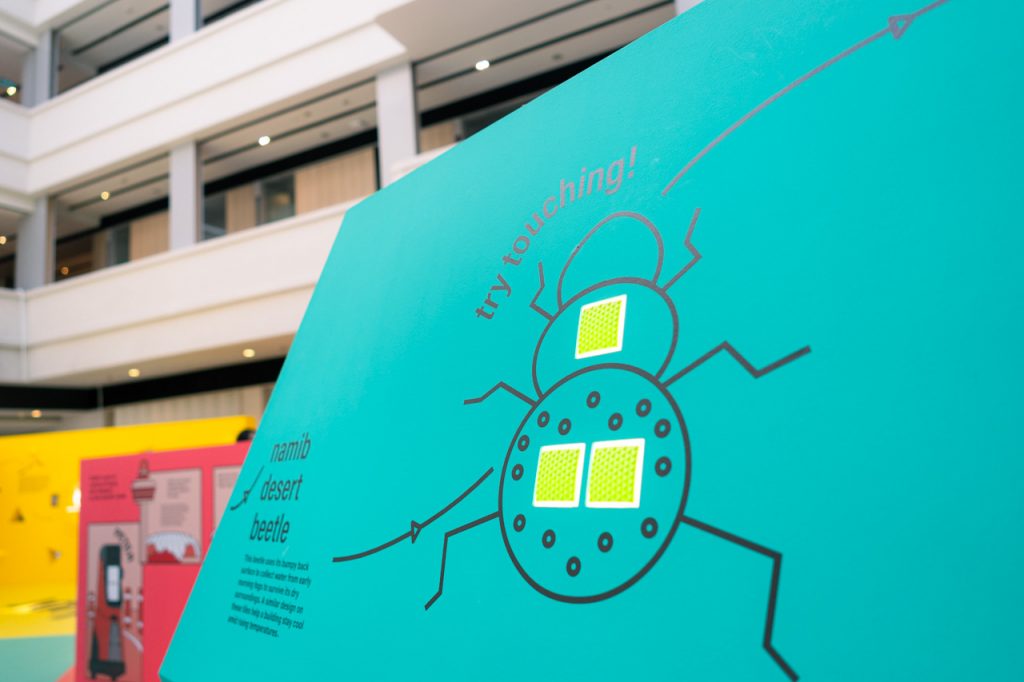

He explains the titles are part of the design practice of biomimicry—inhabiting the cooling properties and exhibiting the “fractal-life bumps and cracks” of an elephant’s skin, meant to cover the facade of buildings in order to cool it—just like an elephant’s skin does. Another type of bumpy tile is shown, moulded after the backs of Namib desert beetles.

These tiles are made of clay and Mycelium, a root structure of fungus—like mushrooms—which has wiry properties that can bind itself with other materials to form cement-like material. The valley of bumps and cracks in these facade tiles makes way for evaporation, creating air pockets to cool the building.

It may not replace air-conditioning, but Jackson’s optimism is infectious. “It is good to have climate control [with air-conditioning], but not at the expense of using electricity,” he notes.

“I’m sure, one day, we’ll get there.”

Another exhibit reconfigures the layouts of migrant worker dormitories—reducing the clutter of double-decker configurations while allowing greater room for bathroom facilities. Next to it, an array of medical prosthetics. Here, these prototypes—from silicon noses to skull caps—focus on subtlety, showing how technology can meet physical disabilities seamlessly.

“Everybody is making a design decision every day,” he tells me as we walk through the exhibits.

“So, it’s good to bring the public in to really look at [these] stories [to be] inspired to contribute.”

Design, A Week Beyond

Sustainability and design have become bed buddies in recent years–and for good reason.

When materials become scarce and supply chains fall apart, reinventing becomes crucial. “Designers can champion their work on [sustainability],” he expands. “But you need everybody to rally behind it, to really adopt the idea of a mindset that you want to be sustainable.”

Jackson isn’t wagging fingers here. It’s just that, even with his confidence in the greater good, he hints that his expertise can only do so much. It’s why his exhibition angles on possibilities–solutions shouldn’t be the end point but a step in the right direction.

“The harder way to solve [things] might be the better way because, sometimes, the short-term thinking [can be] the problem,” he adds. “I think that mindsets need to change, I think, [in order] to be sustainable.”

For example, Jackson doesn’t love Singapore’s litter problem. He laments about trash left behind at local public events that he sees as a recurring trend. It takes more to instill greater responsibility over a problem, he explains, and that sustainability for a better Singapore requires a collective effort.

“Singapore, you got to do better than that, you know?” he says, sighing. It’s the only point in our conversation that he sounds fatigued. But he quickly gathers himself, keeping his optimism in check. With an entire week ahead, it’s the key to showing the public how problems can indeed be made better by design.