One possibility would be the MRT imbroglio, which arguably all started from the simultaneous breakdown of the North-South and East-West lines on 7 July 2015.

And then there’s the event that happened exactly one week prior – the pilot episode of MediaCorp’s long-form drama Tanglin. Since its debut on Channel 5 on 30 June 2015, the long-form English series has gone on to air a jaw-dropping 600 episodes and counting.

It’s an astonishing number, considering that the previous record was held by the Channel 8 drama 118, which ran for 255 episodes from 2014 to 2015. Growing Up, previously SIngapore’s longest-running English drama, aired a mere 128 episodes over six seasons between 1996 and 2002.

But what is Tanglin about exactly, and what makes it so popular?

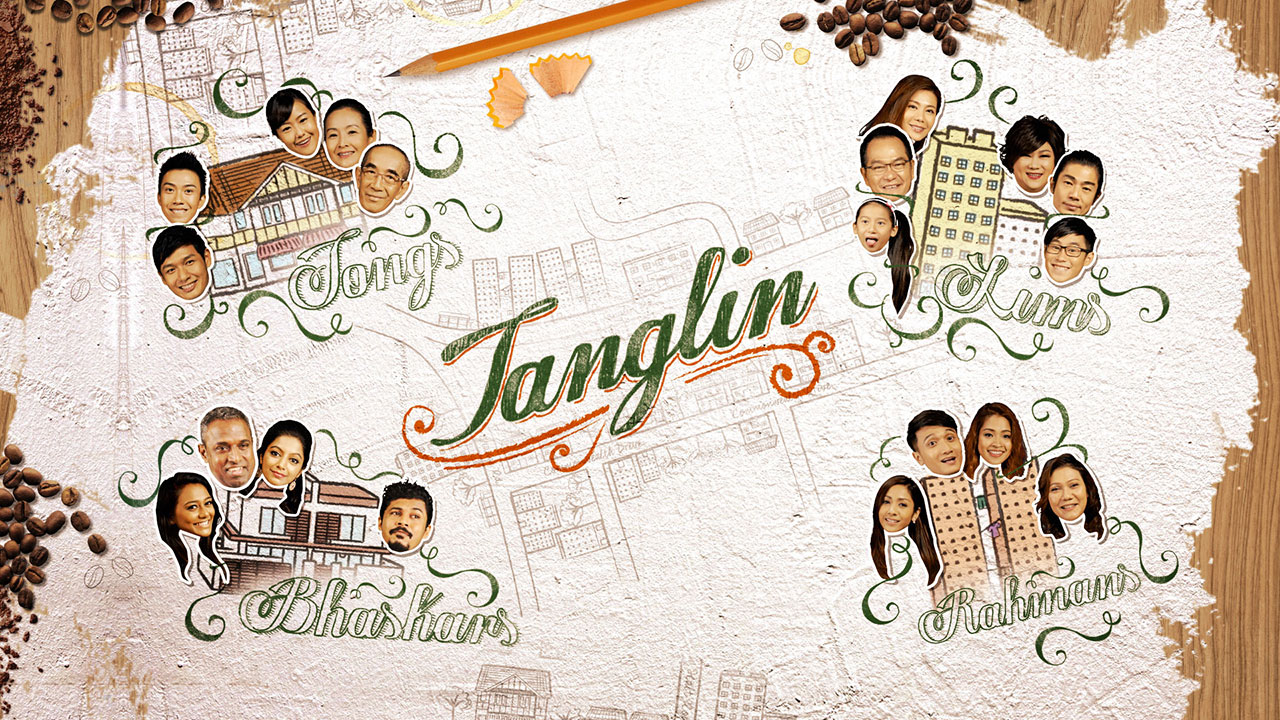

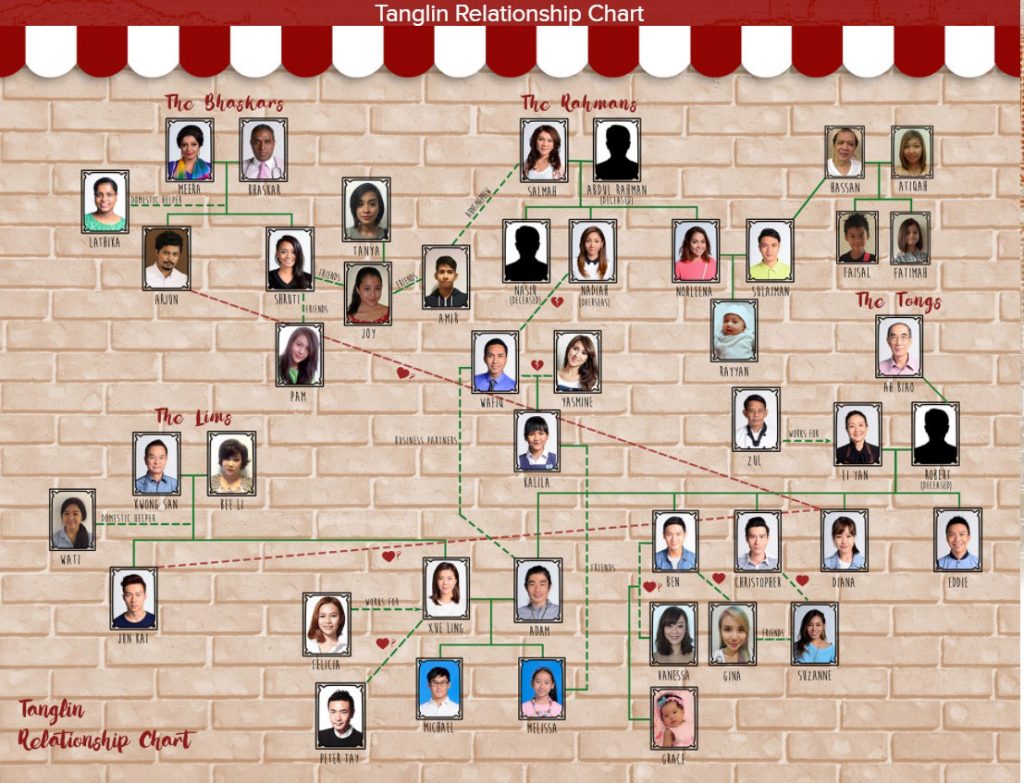

The show centres around four families in the Tanglin neighbourhood: the Tongs, who run the Tanglin Coffee House; the Lims, who run the successful food business KS Foods; the Bhaskars, a formerly expatriate family of medical professionals from India and lastly, the Rahmans, a single-parent family that is preparing to welcome their new son-in-law Sulaiman.

But just tens of episodes into the show and the series was already dragging its feet. Whereas a usual 20-episode drama would build momentum and barrel towards some kind of climax, Tanglin toddled through its early stages.

Take for example Shruti Bhaskar, the new kid on the school block who tries to cosy up to the popular girls in her JC but gets bullied by them instead.

I use the term “bullied” loosely, because the bullying seemed to comprise mostly angry glares and silly pranks, before culminating in the bullies planting a pack of cigarettes in Shruti’s backpack and reporting her to the school.

I don’t advocate bullying in any way, but come on – that wasn’t vile, just infantile.

Over at the Tong family, Michael is harbouring a secret. He leaves the house stealthily and returns with bruises over his body – could he be caught up in some nefarious business?

Turns out that the stereotypical goody-two-shoes student is a breakdancer, and he is furious at his best friend Eddie for not keeping his secret when a video of his dancing surfaces online.

That is one of the fundamental problems with Tanglin – it tends to drag out tension unnecessarily and then end on an anticlimatic note.

To make things clear, I’m not a picky viewer. All I wanted to was good drama, but what I got instead was just humdrum.

Hours into the series, my eyes began glazing over as a result of the monotonous storyline. In a bid to fight off boredom, I started focusing on the sets instead.

And my word, they looked absolutely fantastic.

I learnt that MediaCorp had spent over a million dollars on building a two-storey set, which contains all four family homes and the coffee house. I’m not surprised, because the sets did look like a million bucks.

In fact, I realise I’ve spent so much time inspecting the sets during the episodes that they have given me ideas on how to design my next home in Sims 4.

At this point, I would rather just play the video game instead. Even my Sims lead more exciting lives than those in Tanglin, even if they speak gibberish.

Nearing episode 300, I’m happy to report that there are signs of life in Tanglin.

Other than the brisker plot development, I appreciate the show’s efforts in rooting itself in the actual Tanglin neighbourhood. Outdoor scenes are filmed around the Tanglin Halt or Holland areas, and the title sequence of the series shows the actual location of each of the four families’ homes.

Small details like these, coupled with the multiracial cast, make me feel I’m watching a truly Singaporean drama.

For example, the families fall into different social strata – the Bhaskars are rich and often throw parties in their terrace house; the Lims run a business and live in a condominium with a domestic helper; the Tongs live in a shophouse above their coffee house; the Rahmans are all salaried employees who live in a HDB flat.

Furthermore, the new Rahman son-in-law Sulaiman is a regular in the Singapore Civil Defence Force. Coincidence, or an intended reflection of Singaporean society?

On a more positive note, there is a subplot about a project to record the heritage of Tanglin.

Tong Ah Biao’s (the father of Tong matriarch Li Yan, who runs Tanglin Coffee House) motivation for taking part in this project goes further than simply recording the neighbourhood’s history. He is nostalgic for the good old days of the neighbourhood, even as he is resigned to old haunts being demolished and the neighbourhood evolving.

This subplot does not go anywhere in particular, but it brought to mind what I read recently about community-driven heritage projects. If Ah Biao’s mentality sounds like a subliminal message from the government that conservation should not stand in the way of progress, it probably is.

I don’t begrudge the show for incorporating the establishment’s point of view, and I know storylines like these are hardly as interesting as romantic trysts or cloak-and-dagger intrigue.

But as a show rooted in Singaporean society and culture, it would be remiss for Tanglin not to cover local topics like the above.

Look at it this way: Conservation of our history is a hot-button topic. Just look at the sagas centred around the Bukit Brown cemetery and the MRT route of the new Cross-Island Line.

Until now, nobody has a good answer that will please both those who want preservation and those who want progress. It’s a topic that needs further public debate, and a mention on a popular television show can only be good for furthering that.

Now, I wonder if I will see an episode where an MRT breakdown occurs. Would Mediacorp have to spend a million dollars to create a flooded tunnel?

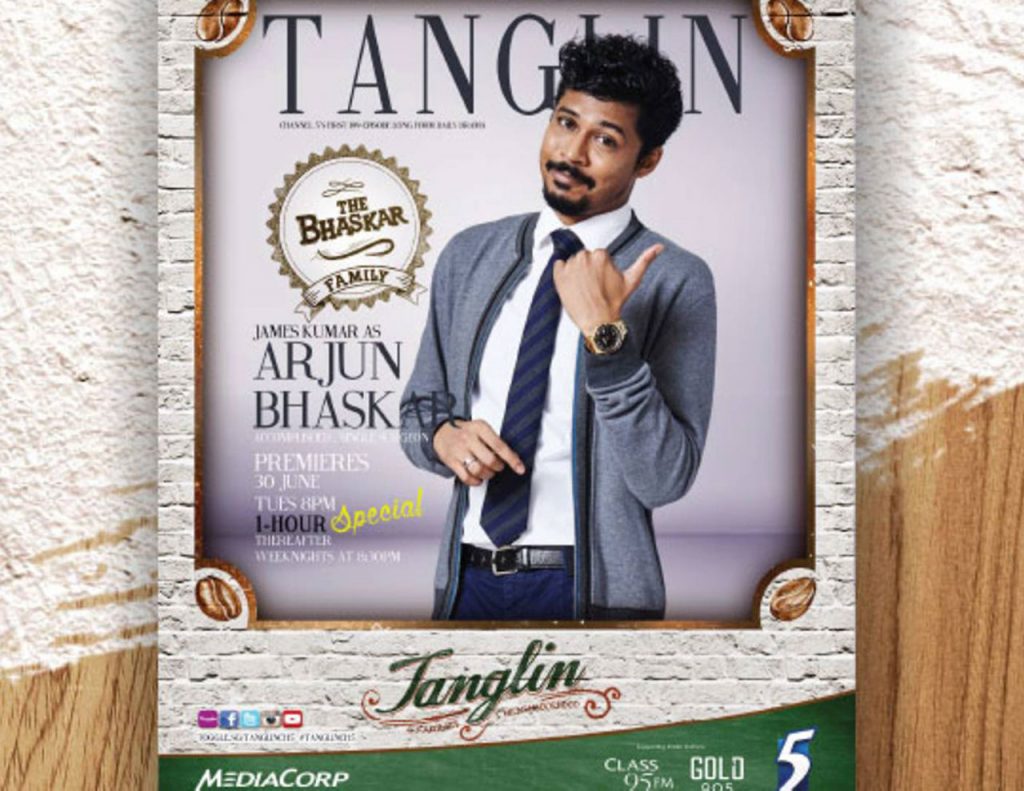

It’s only fair, since Arjun probably has had the craziest time of all the characters in Tanglin. To recap: Arjun had a girlfriend (Diana Tong) whom he broke up with but still pines for; he fought off a spate of cancer, became a playboy and stopped being a playboy; worked as a surgeon before changing his specialisation in paediatric care, and got framed for behaving inappropriately towards a teenage patient.

Now, he’s onto a new love interest, but his relationship with Diana is still not resolved.

I can confidently say that the show has finally built the momentum that I complained it lacked in its first 20 episodes.

Long-lost children from past affairs have returned to complicate relationships between former lovers. Characters have gone to prison. Romance continues to bloom in a tangled web of relationships.

While I find the show’s heap of subplots sprawling and maddeningly difficult to track, the plot’s complexity means that guest stars can lend star power when they drop in during occasional episodes. For instance, Singapore Idol winner Taufik Batisah has a recurring role, and so does Singapore’s classic hit Tay Ping Hui.

Sure, if I dip into new shows, I get to immerse myself in new settings and new characters. But with Tanglin, I know what I am getting into. I truly know these characters.

After all, familiarity matters, doesn’t it? If I had watched these characters from the first episode to episode 600, I would naturally have developed an attachment – no, a loyalty – towards them.

At this point in its run, Tanglin isn’t just a television show. It’s a ritual for the regular viewer.

Having crammed its lore in a few weeks, I feel like I know these people, even though they are fictional. I could almost be part of their extended family.

Indeed, there are still occasional storylines which I do not care for. But I know their traits and flaws of these characters, and I cherish the good and accept the bad Isn’t this what family is?

At this point, I notice I’ve neglected Sims 4 in favour of Tanglin. The game icon seems to shimmer on my computer screen, imploring me to return and sink a few hours into the world of my avatar Arjun.

I’ll go back to the game eventually. Just one more episode of Tanglin first, or maybe two? Damn it!