This column is the fourth in a four-part series that explores how money, for better or worse, can often complicate what should otherwise be straightforward relationships between people.

We’ll talk about it and its complexities in Singaporean life. In other words, whether I will get a bonus this year, why I shouldn’t be buying more clothes off ASOS, and whether I have enough savings for my own house so they can finally evict me.

And then, as though these discussions were all a planned charade leading up to the only actually important question, my mum would ask, “Has your pay come in already? Why have you not given us our allowance?”

To which I would simply mumble, “Okay I’ll withdraw from the ATM when I have time.”

My mum does not believe in the security of internet banking.

I frequently ask myself if this fuss is necessary. After all, my parents still run their own company and remain in good health. Money is not an issue in the family.

I know that in some families, this is considered a kind of “token rent” for living with your parents who pay the utilities. And it’s also a way to show gratitude for the comfortable life they have provided us with.

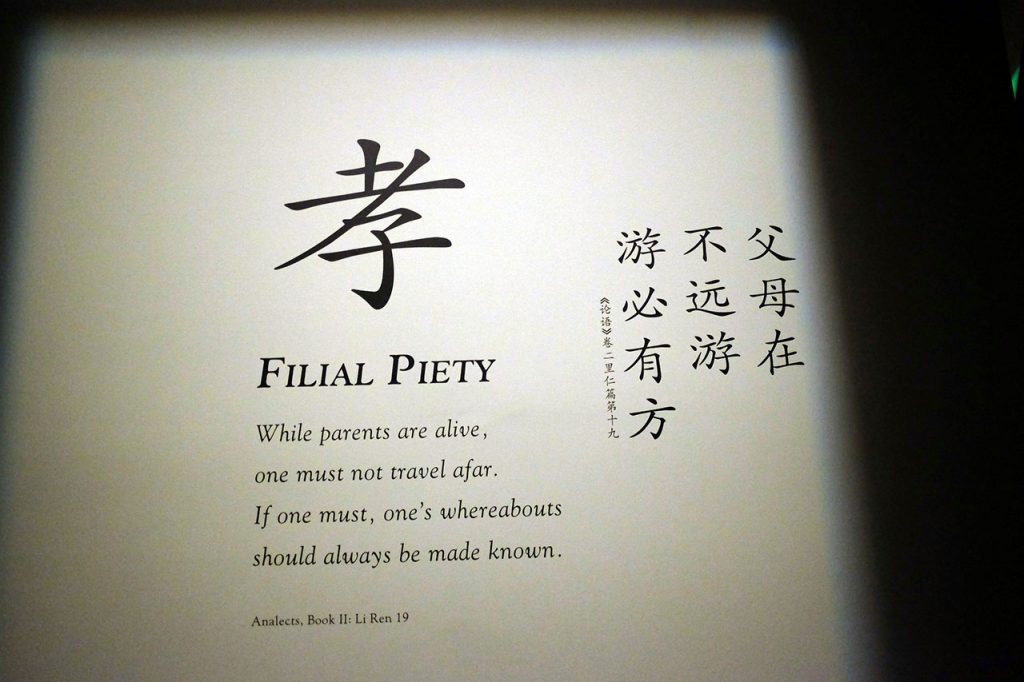

Giving our parents an allowance, therefore, is a display of modern-day filial piety.

This is ingrained in Singaporean Chinese society, and shame on you if you, a Chinese working adult, do not comply.

Jamie, a working mum, tells me, “My mother just told me the figure that I had to give her, which she calculated based on my income, and I obeyed.

“I grew up in a very traditional Asian household and was brought up with the expectation that it is my responsibility to take care of my parents when they grow old. It is not an option.”

I’ve never openly questioned this obligation at home for fear of opening a Pandora’s box of “past debts” that I already owe to my parents – school fees, petrol usage for the countless times my dad drove me to school, and of course all the family meals, among other duties that my parents have fulfilled.

But what if we have misunderstood the basic proposition of filial piety? Since when did the notion of a family entail a compulsory financial transaction?

In his teachings of filial piety, Confucius never singled out obedience in the form of material paybacks. But the concept has evolved to ensure that an “allowance” is now a mandatory restitution.

K N Knapp, an American professor who specialises in China studies, writes:

“In early China, besides expressing love or care, the presentation of food, or by extension material support, creates obligation. If one feeds a man, he is obligated to repay your kindness.

This sense of obligation was so strong that it could be used as a means to control others. In the same way, a child is obligated to repay his parents for the food and care they provided him as a helpless child.”

The idea of service and “providing for someone” is greatly emphasised in Chinese familial relationships, and has resulted in the Chinese preoccupation with money and material well-being, writes Hong Kong-based journalist Aris Teon.

On that note, the oft-quoted Chinese expression 饮水思源 (yin shui si yuan) has also been misconstrued to fit a materialistic society.

Its original meaning is to not forget where one’s happiness comes from, and reminds us to pay gratitude and loyalty to those whom we have received favours from.

Today, it is justification for a financial transaction within the family, as though one is legally bound by an ancient idiom to open his wallet.

The idea of service and “providing for someone” is greatly emphasised in Chinese familial relationships, and has resulted in the Chinese preoccupation with money and material well-being.

Our grandparents, being in the Pioneer Generation, did not have the luxury of full CPF and other forms of insurance that would tide them through their old age.

An allowance is therefore necessary to ease their burden.

For millennials, however, giving money on a monthly basis should not be the only way to accord our parents recognition, assuming that the family is relatively well off (and not considering situations where the children in a lower-income family go on to do really well in life). If parents are still working labourious or menial jobs, then an allowance would no doubt go a long way to making their lives more comfortable.

Is buying the occasional meal or just plain quality time today not sufficient to meet the terms and conditions of filial piety?

Now don’t get me wrong. A part of me does want to give my parents an allowance. Yet I believe that gestures of respect should not be a product of emotional manipulation.

I should not be giving my parents an allowance as a response to their guilt-tripping, when most of the things that they have done for me are simply fundamental parental duties. If I should dare to be a little insensitive, I might even argue that they chose to have me — I did not choose to be born.

Parenting is no doubt a costly investment, but it also should not revolve solely around economic dividends. I have often heard it said that having children is your investment in your own future. But to me at least, this is unreasonable. If you choose to have children, you are also choosing for them to decide how they want to live their lives or express their emotions.

This view largely also stems from the expectation of a “reciprocal bargain”: children should get a good job with a university degree so that in time, they can give their parents a comfortable life.

Call me a selfish millennial, but in all honesty I need my money more than my parents do at this point in time. Perhaps when I’m earning a lot more in a few years, I might feel differently.

But as it is, the cost of living is simply too high. The housing market and the economic climate many of our parents enjoyed no longer exists for us. How am I going to buy that HDB flat and move out as soon as possible, as my mum so dearly wishes?

Which is why when I took a pay cut for a new job, I also reduced my allowance for my parents by the same percentage. I thought this was only fair.

My mum wasn’t too pleased.