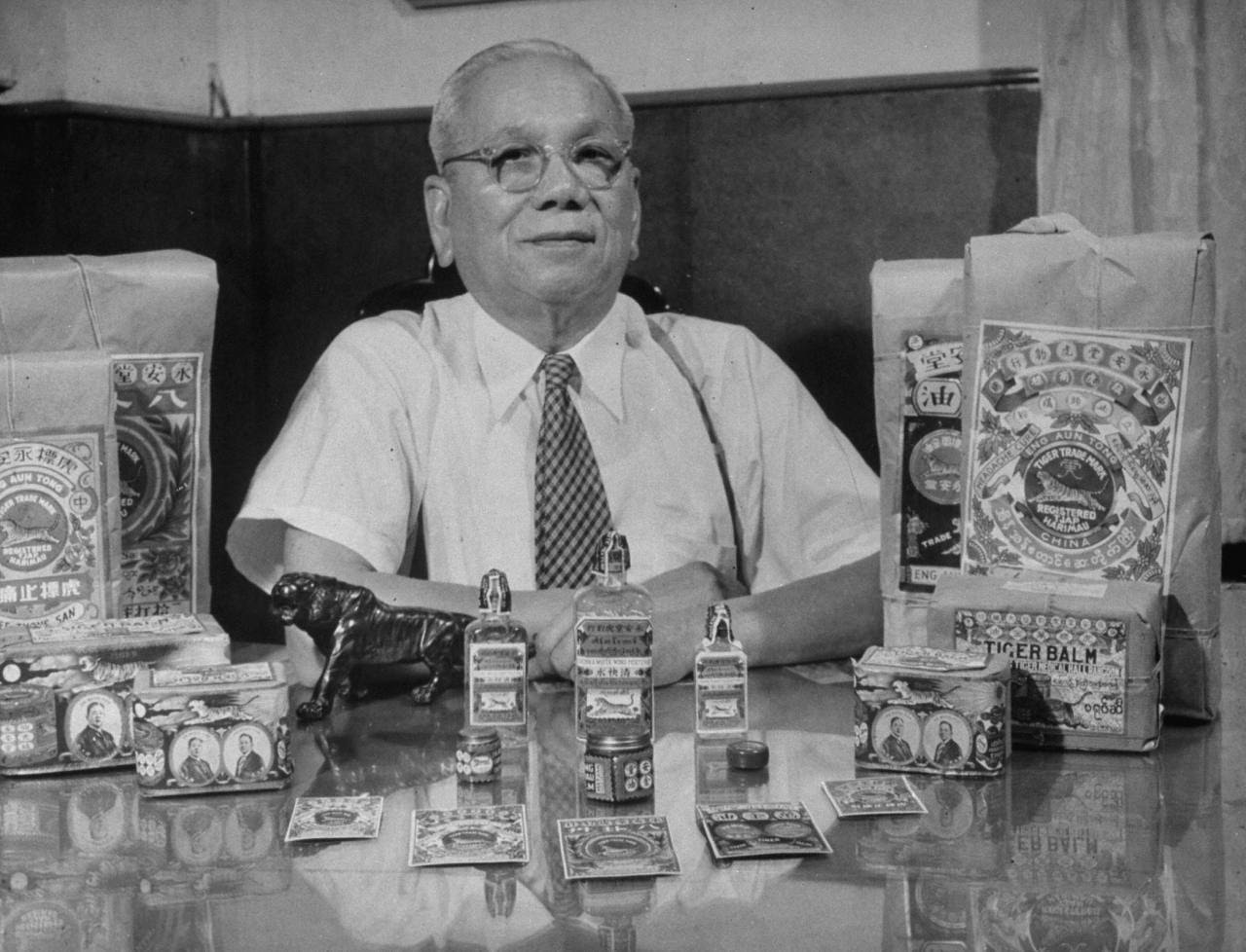

Top image: Aw Boon Haw, courtesy of Journeys Pte Ltd.

It all started with a cigarette.

The Tiger Balm King roared as the glowing end of a matchstick fell into his lap, burning a hole in the leg of his flashy sharkskin suit. Somehow, his already bad day had just become worse.

ADVERTISEMENT

If you were a wealthy Chinese businessman in the 1930s, the elite Ee Ho Hean Club was the only place to be on a Thursday at dusk for gambling night. Unfortunately, Aw Boon Haw, known as the Tiger Balm King, had not won a single hand all evening.

And to top it off, there his expensive suit was ruined by a careless cigarette-smoker who proceeded to patronize him with promises of a new pair of trousers, no, ten pairs of trousers, and then the satisfaction of a virgin girl.

The Tiger Balm King’s rage only grew. Did the man seriously think he couldn’t afford a pair of trousers? Or that he routinely deflowered virgins? It was nothing short of an insult to his ego.

“No, I demand some other satisfaction,” he growled. “Are you man enough to cut a deck of cards for fifty thousand dollars? Or don’t you have the balls for it?”

The ruins of faded glamour

On my last visit to Haw Par Villa, I spotted a Chinese-style pavilion on my way out of the park. Initially enticed by the prospect of air conditioning, I decided to double back for a quick look.

It turned out to house a small exhibition dedicated to the lives of Aw Boon Haw and Aw Boon Par, the dynamic duo behind Haw Par Villa.

Despite their mortality, the lives of the Aw brothers were no less colourful or bizarre than anything their neighbours in the sculpture garden might have to offer. Theirs is a tale of unimaginable wealth and many (teenage) wives. It features everything from a bitter business rivalry born at the card table of an elite merchant’s club to a car that was shaped like a tiger (and roared like one too), a pair of solid gold spectacles, a Russian princess… and an eerie deathbed prophecy.

At the heart of it all is a family who experienced the full swing of the pendulum of life between immense riches and immense tragedy.

In other words, it is a story that could pass for the screenplay of a Crazy Rich Asians prequel.

Crazy rich Asians

Aw Boon Haw and Aw Boon Par were born the second and third sons respectively of a poor Hakka herbalist. Although ethnically Chinese, the brothers were born in Rangoon, Burma, where their parents migrated to escape war and poverty years earlier. The family operated a small medicine hall in Rangoon, where they dispensed affordable herbal remedies to other overseas Chinese and the locals.

While their father initially planned for both his sons to receive an English education, Boon Haw proved to be what most teachers nowadays would call a paikia. He frequently skipped school, roamed the streets, got into fights, and came home bruised and battered.

ADVERTISEMENT

Eventually, after he was expelled from school for beating up his teacher, Boon Haw was packed off to China. Meanwhile, Boon Par continued to be educated in Western ways.

The two brothers were finally reunited after the death of their father (who had pretty much given up on Boon Haw) when Boon Par took over their father’s business. Together, the brothers developed and improved the ointment that would eventually become their claim to fame: Tiger Balm.

Scandals and fury

To know how wealthy the Aw family was, look no further than Chapter 17 of Sam King’s memoir, Tiger Balm King.

It recounts a gambling contest that took place at an elite Chinese merchant’s club. Allegedly, Boon Haw challenged a fellow businessman to a bet of fifty thousand dollars on the draw of a single card, then doubled down and increased the pot to two hundred thousand dollars when he lost the first draw.

Unfortunately, the wager was prematurely broken up by Tan Kah Kee, a Hokkien rubber tycoon better known today as the benefactor of Hwa Chong Institution and the namesake of the Downtown line MRT station. A club member himself, he happened to be listening nearby when he decided that he “had had enough of watching this scant regard for money”.

Boon Haw then threw down an even more reckless challenge to Tan Kah Kee. He would play Tan Kah Kee in any game he chose for any stake he cared to make. In “a tone bordering on contempt”, Tan Kah Kee replied that he did not take money from foolish people.

Boon Haw was utterly humiliated and vowed vengeance.

This snub was supposedly the incident that birthed the fierce (if somewhat one-sided) rivalry between Aw Boon Haw and Tan Kah Kee. Both men were seen as prominent leaders of the Chinese business community, and they both owned newspapers.

Reportedly, one of the reasons that Aw Boon Haw set up his own newspaper, the Sin Chew Jit Poh, was to counter the influence of Tan Kah Kee’s Nanyang Siang Pau. Ironically, the two papers founded by these two bitter business rivals were merged in 1983 to form what we now know as Lianhe (or “Alliance”) Zaobao.

But records of the Aws’ philanthropy also paint a more positive picture of how they spent their immense wealth. When the brothers incorporated their business into Haw Par Brothers in 1932, it was written in the company’s charter that up to 50 per cent of the company’s annual profits could be donated to charity.

“The brothers focused their philanthropy in four areas: hospitals, schools, orphanages and homes for the elderly,” explains Eisen Teo, senior researcher at Journeys Pte Ltd, who manages Haw Par Villa. “For hospitals, they donated US$55 million to medical facilities in China, Hong Kong and Bangkok. For schools, they gave almost US$20 million to primary schools and universities.”

Other causes the brothers generously supported included war bonds, flood and fire relief, refugee aid, building and restoration of temples and homes for the poor.

An example of an act of philanthropy in Singapore that has survived is St. Theresa’s Home, located at Upper Thomson Road. In the 1930s, the Aw brothers donated S$60,000 towards its construction.

There is also another juicy (but unverifiable) anecdote in Tiger Balm King about an encounter between Aw Boon Haw and a fallen cabaret girl who claimed to have been born the daughter of a Russian Count. Separated from her fiance and stranded in Hong Kong, the woman had initially planned to prostitute herself to Aw Boon Haw for her travel fare. Instead, she broke down in tears before he could do the deed. Sympathetic to her plight, Aw Boon Haw allegedly decided not to bed the “Russian Princess” but gave her five thousand dollars anyway, allowing her to reunite with her lover in England.

Lavish, but also crazy lives

Aw Boon Haw was the marketing genius behind Tiger Balm, and that meant he lived to grab people by their eyeballs. He wore a pair of 18-carat gold spectacles (according to Sam King, he tried to push for 24K, but the spectacle-maker objected as the metal would be too soft) not because of any deficiency in his eyesight, but because he thought they made him look more educated.

He also drove a flashy German NSU with a hideous custom tiger head that was the talk of the town. Sam King sums up the car as follows: “No animal, no matter how beastly, had ever been so maligned as that grotesque specimen of a tiger.”

“Mainly, the juicy stories [about the Aw family] would be from the Sam King book because Sam King had unparalleled access to the inner circle of the Aw family,” says Eisen. “The book is a reconstruction of Aw Boon Haw’s life based on interviews with the members of the Aw family and employees of Aw Boon Haw.”

While the two brothers might have got along swimmingly, King’s book describes the tensions between the brothers’ (multiple) wives. Boon Haw had four wives and Boon Par, three.

According to Eisen: “Generally, there was an ‘uneasy peace’ among the wives. This was due to three factors. Firstly, it was deemed acceptable in the early 20th century for rich Chinese men to have multiple wives and concubines. The second factor is that the brothers were some of the richest men in Southeast Asia, so they could use their immense riches to placate their wives whenever they were upset with them. The third factor is that [Boon Haw] had multiple residences in different cities so that he could keep [the wives] apart for part of the time.”

Nevertheless, the brothers’ families were close. When Boon Par breathed his last on 7 September 1944, he was attended by two of his sisters-in-law. This meant that they also had the dubious honour of bearing witness to his deathbed prophecy regarding their husband: “My dear brother will survive me by ten years.”

Eerily, Boon Haw died in Hawaii from a heart attack on 4 September 1954—just three days short of his brother’s chilling prophecy.

But this was just one of the multiple streaks of misfortune felt by the Aw family. Two of Boon Haw’s sons died during World War II as toddlers. His favourite son Jee Haw was killed during an air raid while another, Sar Haw, died of cholera. Aw Hoe, the son who was the designated heir to Haw Par Brothers, predeceased Boon Haw in a plane crash in 1951. At his death, Aw Hoe was just 30 years old.

Upon Boon Haw’s death, Haw Par Brothers went to his nephew Aw Cheng Chye, one of Boon Par’s sons. Unfortunately, the family would suffer a “double tragedy” in 1971.

First, the Aw family lost control of the business in a hostile takeover in June 1971 to a London-based firm called Slater Walker. Intending to utilize British expertise to expand his own company, Cheng Chye was instead played out by the Londoners, who accumulated just enough shares to gain control of Haw Par Brothers. When two of the original six family directors resigned from the board, the five Slater Walker directors became the majority, forcing Cheng Chye to yield authority but remain chairman. In his place, the mastermind behind the takeover became the executive director managing the company.

Then, shortly after the takeover, Cheng Chye suffered a stroke while on holiday with his family in South America and died in Santiago, Chile, on 22 August 1971.

One conspiracy theory that Sam King gives for this series of tragedies is the seven-tier pagoda that Aw Boon Haw built as part of his lavish Hong Kong home. According to Boon Haw’s first wife, building a seven-tier pagoda would bring tragedy to be repeated thrice. Unfortunately, this is one of those explanations that raises many more questions than answers.

“I don’t know why no one has done a drama series about them yet,” muses Eisen. “Can, right?”

The Secret Life Of Haw Par Villa

While there might not be a drama series or a film yet, local theatre company Strawberries Inc has put together The Secret Life Of Haw Par Villa. The production (which has already sold out for the rest of January) is a site-specific theatre performance that features an after-hours tour around the park, led by a semi-fictionalized version of Aw Boon Haw.

I had the pleasure of attending the performance a while ago. “Aw Boon Haw” (played by Benjamin Chow) was portrayed as an eccentric Confucius fanboy and costumed in a distinctive two-tone red/tiger print pantsuit, striking me as the delightful missing piece of an unholy trinity completed by PT Barnum and Willy Wonka.

“I think you can’t do a show in Haw Par Villa without the ‘Haw’ and ‘Par’,” said Krish Natarajan, director of Strawberries Inc and also the playwright of The Secret Life of Haw Par Villa, explaining what had inspired him to incorporate the personal stories of the Aw brothers into the play alongside mythological characters like Lan Caihe and Sun Wukong.

“The brothers are so intertwined with the park, and I felt it was important to include them in the experience. Having Boon Haw lead the group grounds the tour in real events which are complemented by the fantastical inhabitants of the park.”

While Krish took reference from the Sam King book while writing the script, he also cautions against confusing his story for history. Some of the elements of The Secret Life, such as the portrayal of Boon Haw as a Confucius fanboy (in a game segment called “Confucius Got Say Or Not”) and a fictional “sibling rivalry” with a more-progressive Boon Par was dramatized with “a lot of artistic licences”.

Returning to my initial impressions of the Aw brothers, I finally know why they stood out to me that day in front of the Jade House. In a park teeming with mythological creatures like Sun Wukong and the Eight Immortals, the subjects of the Jade House exhibition stood out because they were real. But it wasn’t just the fact that they were once real people who lived in 1930s Singapore or that their story was set in a time closer to mine than any other I could find in the bright and bizarre park.

Haw Par Villa might have started out as a statue park to educate the public on matters of morality. But perhaps the most significant lessons – on business, life, family, morality – are to be gleaned from the lives and fortunes of the Aw brothers themselves.

And, as we ring in the Year of the Tiger, perhaps a director out there will be inspired by and finally give these Tiger Balm brothers the film treatment they deserve.

I know a flashy Tiger Balm King who would certainly approve.