Top image courtesy of Vue Networks/Asian Film Archive.

As a little kid, some of my fondest memories of my grandparents were forged through our mutual admiration of vintage Singaporean cinema.

While I binged on cartoons and anime in the mornings and caught reruns of American sitcoms over the weekends, I watched classic Malay movies on late-night TV. My grandparents would frequently let me stay up way past my bedtime, even on school nights!

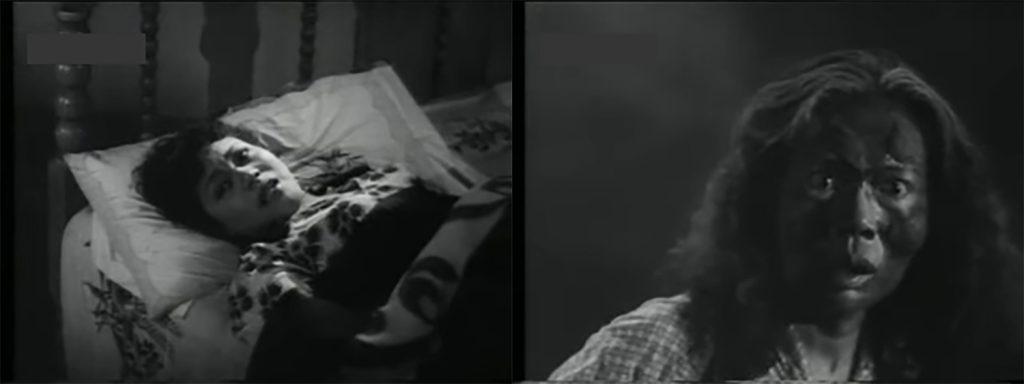

We shared laughs over the antics of the Bujang Lapok bachelors. I faced my own nightmares after screaming through Sumpah Pontianak. These late nights were my gateway to the richness that local cinema had to offer, and it goes back decades.

The Golden Age

Once dubbed the Hollywood of Southeast Asia, Singapore’s filmmaking industry was a formidable presence in the region from the late 1940s to the early 1970s.

Academics call it the Golden Age of Singaporean Cinema. It’s hard to argue with that, what with the sheer amount of films that came out of that period.

Singaporean films flourished under the auspices of Cathay Organisation and Shaw Brothers. Both now exist as popular cinema chains, but back then, they were film production powerhouses.

Shaw was founded and headed by Shanghainese siblings Run Run and Runme Shaw, who invested heavily by not just opening a chain of theatres (19 in total) but also by building up their own stable of directors, producers, actors, and crewmembers.

After the Japanese Occupation, Shaw set up a base in Jalan Ampas in 1947 for their hugely prolific Malay Film Productions, which would go on to release 162 acclaimed films over the next two decades. Titles range from tragedies like 1962’s Ibu Mertuaku, to comedies like the Bujang Lapok franchise, to period epics like 1956’s Hang Tuah.

These films—besides being incredibly well-crafted—were hyperlocal and hyperspecific to Singaporean sensibilities. They also offered a romanticised window into Singapore’s Malay heritage.

These hits launched the careers of superstars such as filmmaker Jamil Sulong, who awed audiences with his storytelling finesse, and the charismatic P. Ramlee, who could make viewers laugh, cry or swoon through his multi-talented Midas touch as an actor, singer, composer, scriptwriter and director.

They were not without competition–business tycoon Loke Wan Tho and film producer Ho Ah Loke founded a new venture, Cathay-Keris, in the 1950s, poaching talent from Shaw.

What they lacked in expertise and experience, they made up for with very lucrative contracts. Music composer Zubir Said (yes, that Zubir Said), who would go on to soundtrack Cathay’s highest-profile films, was one of many who jumped ship.

Cathay already made headway in new traditions–they broke away from the bangsawan (traditional Malay opera) genre, produced the first local movies shot in colour (1952’s Perwira Lautan Teduh and 1953’s Bulan Perindu), and paved the way for Southeast Asian horror cinema. In particular, their Pontianak trilogy was tremendously successful. Thanks to region-appropriate dubs, these films found audiences in Hong Kong and the US.

Post-Independence Decline

The rivalry between these two major studios spurred Singaporean cinema to new heights during this boom era, producing hundreds of local classics that still have a profound cultural impact today.

Hussein Haniff’s Hang Jebat is widely considered to be the definitive take on the Malaccan legend of Jebat, the silat rebel. Films like Orang Minyak and the aforementioned Pontianak films helped immortalise and ingrain the supernatural folklore of the Nusantara into the psyches of future generations.

Unfortunately, Singapore’s independence marked a deep hibernation for its film industry. Social unrest, and a talent drain of creatives–a large swath of producers, directors and actors chose to relocate to Malaysia, which had a larger market–were enough to make an impact.

But general interest in Singaporean productions was dwindling. More and more households began to own television sets, and audiences’ attention were diverted to a new type of cinema: Hollywood. Our economy’s shifted focus on rapid industrialisation over the arts (as detailed in Raphaël Millet’s book Singapore Cinema) added to the steep decline.

By 1967, Shaw had shuttered, and Cathay followed suit in 1972. After that, only eight local films were produced–this included Singapore’s first martial arts flick, Ring of Fury, directed by James Sebastian.

The independent film, filmed guerilla-style at several locations secretly without permits, couldn’t even nab a local release until 2018. Asian Film Archive (AFA), which documented its modest but difficult production process in a 2020 interview with its late director, embarked on a restoration project based on a surviving 35mm reel kept by its lead actor Peter Chong.

Between 1977 and 1991, however, there were none, save for regional co-productions like They Call Her… Cleopatra Wong, which made a cult icon in Singaporean Marrie Lee. And then there was 1979’s Saint Jack, a gritty Peter Bogdanovich-helmed drama that was shot entirely on-location here.

Otherwise, the Golden Age dimmed. Its industry flatlined.

A Glimmer of Hope

While seemingly cold and rigid, Singaporean filmmaking was not left in the dirt. In 1987, the first-ever Singapore International Film Festival (SGIFF) was founded.

Established by a team of film buffs, led by the architect of Singapore’s first multiplex and former actor, Geoffrey Malone, the festival was primarily started to inspire wider public interest in World and Asian cinema.

As Malone stated in a 1986 interview with The Straits Times, the festival was designed “to give them a chance to watch films that they wouldn’t usually be able to see in a cinema here.”

Beyond that, the fest was also set up to nurture and showcase homegrown filmmaking talent on a global platform. The shot in the arm worked, inspiring burgeoning auteurs like Eric Khoo, whose career kickstarted when his short film, August, won Best Short Film at SGIFF’s Silver Screen Awards in 1991.

At the same time, Singapore’s first English-language film, Medium Rare (aka The Medium), loosely based on the Toa Payoh ritual murders of 1981 and cult leader Adrian Lim, would be released–it ended a 14-year dry spell for local productions.

Medium Rare producer Errol Pang financed most of its budget (S$1.84 million) out of pocket. It was a critical and commercial failure.

“I get asked if I am ashamed for the work I have done for it, and I have to remind myself not to be defensive,” Medium Rare actor and writer Margaret Chan told Sinema in 2006 as she recounted the film’s public reception.

“What is there to be ashamed of? They were expecting high production values, but they forget that this was our first film and Singapore’s first film in a long time. We were flying by the seat of our pants!”

The movie was a costly revival for the Singaporean film scene. But it was, definitively, the start of a renaissance.

Mid-90s Film Renaissance

In a different timeline, the film that would have sparked a resurgence in Singaporean cinema would be Shirkers.

That film, which ended up the subject of an acclaimed 2018 Netflix documentary of the same name, had a production process plagued by calamitous twists that prevented its completion.

In its stead, Khoo’s vibrant 1995 debut feature, Mee Pok Man, ushered in a new kind of Singaporean cinema. The film initially caused a stir with its R(A) rating (now classified as R21): it never held back on its dark subject matter—including depictions of necrophilia—and bleak perspective on Singaporean life, touching on consumerism and alienation.

Looking back, Mee Pok Man was the trailblazing catalyst for the new wave to come. It was the first local feature to compete for the SGIFF’s Silver Screen Awards, and it was subsequently invited to over 30 prestigious international film festivals.

That same year, an equally provocative movie called Bugis Street by Hong Kong filmmaker Yonfan was released, following the lives of Singaporean transvestites and transsexuals in the titular district.

Featuring full-frontal nudity and queer themes, this film may not be as fondly remembered today —it was banned after a few short weeks in cinemas before being restored by SGIFF decades later in 2015. But its nostalgic illustration and empathetic humanisation of a hidden Singaporean subculture, combined with grit and captivating visuals, should be applauded.

If 1995’s arthouse offerings showcased the artistic vision of Singaporean filmmakers, a comedy like Army Daze proved its box office viability.

Ong Keng Sen’s 1996 hilariously relatable take on National Service–adapted from a 1987 play by Michael Chiang–focused on a motley crew of six teenagers enlisting for every Singaporean male’s rite of passage.

Its multiracial cast of characters rendered a Singapore that was never seen on the big screen before: Singaporeans emerging from different economic and ethnic backgrounds, underlined by a funny and feel-good streak that went hand-in-hand with absurd humour.

The following year, Khoo would cast a wider net on Singaporean life in his sophomore feature 12 Storeys. Centred around several households living in the same HDB flat with stories intertwined with skilful intricacy, this social drama gave an eye-opening look into the latent anxieties of everyday citizens.

Besides garnering worldwide acclaim and Singapore’s first-ever entry into the Cannes Film Festival, 12 Storeys was also notable for introducing Jack Neo to the big screen. Unlike his broadly comedic TV work (which he would carry over later), Neo’s nuanced and intimate performance as a naive soup vendor, Ah Gu, was a revelation.

Box Office Boom

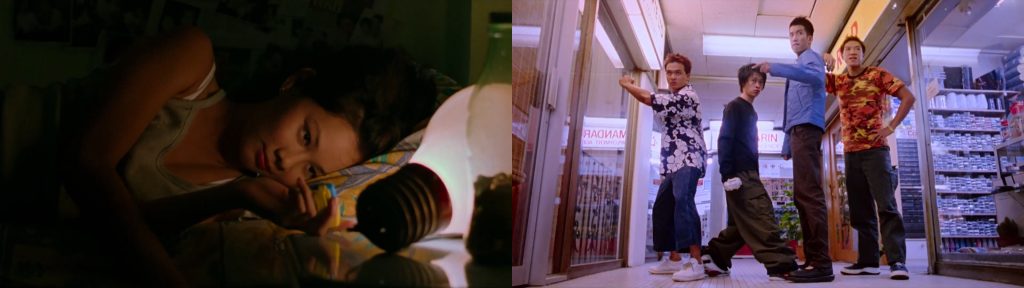

1998 arrived with pomp. It saw the release of three iconic films that would become pivotal in the revitalisation of Singaporean cinema: Tay Teck Lock’s Money No Enough, Glen Goei’s Forever Fever, and Phillip Lim’s The Teenage Textbook Movie.

In particular, the phenomenal commercial success of Money No Enough—grossing over S$5 million dollars—was crucial in the nation’s renewed drive towards movie-making.

Written by and starring Neo (alongside the cast of Comedy Night, an immensely popular Chinese-language series), this working-class satire of Singapore’s materialistic mindset would herald the filmmaker’s incredibly lucrative run that continues to this day.

Likewise, Forever Fever was also significant because it was the first local film to be acquired for global release by distributor Miramax, who paid a cool S$4.5 million for the rights. Set in the 1970s, the infectiously joyous musical comedy featured a young Adrian Pang as a supermarket employee with ambitions of winning a disco dance competition.

Meanwhile, The Teenage Textbook Movie–based on the bestselling novel of the same name (and its sequel, The Teenage Workbook) by late author and lawyer Adrian Tan–became an instant cult classic among Gen X youths. It topped the Singapore box office for weeks.

Even this tween (at the time) millennial identified with The Teenage Textbook Movie’s uniquely local adolescent perspective, certainly much more than the adult-oriented local films of that decade. While American teen dramas saturated local TV and theatres, seeing the same coming-of-age tropes and stereotypes play out within the specificity of our environment and cultural prism made it seem all the more authentic and relatable.

The film adaptation starred Melody Chen and Caleb Goh in their breakout roles: as teens figuring out love and life at the fictitious Paya Lebar Junior College. It also propelled the career of John Klass, who wrote and produced the film’s amazing soundtrack, leading to a string of chart-topping songs across local radio during that period.

The hot streak continued into 1999, which saw the inauguration of Raintree Pictures, a subsidiary of MediaCorp Productions. It produced the wildly successful Liang Po Po: The Movie (a spin-off from Neo’s TV cross-gender character) alongside a number of Neo’s future projects. That year alone spawned eight Singaporean features, including Neo’s directorial debut That One No Enough.

But of all the local releases before the turn of the millennium, none were as off-the-wall as Kelvin Tong and Jasmine Ng’s “motorcycle kung-fu love story”, Eating Air.

Despite not being as profitable as its contemporaries, Eating Air (co-directed by Ng, who was also one of the three women behind the unfinished Shirkers) bristles with punk rock spirit and anarchic energy. The film was the perfect counterpoint to the unambitious crowd-pleasers that dominated mainstream domestic productions.

The 21st Century and Beyond

The momentum from the mid-90s renaissance continued to snowball into the 21st century. From highbrow to lowbrow, from quality to quantity, by any metric–the thriving local film industry is the healthiest it’s been in quite some time.

There’s the proliferation of Neo’s slapstick empire–one that dominates the box office despite mixed reception–and the continuation of Khoo’s dramatic vision. Beyond that, there’s the emergence of extraordinary auteurs: Royston Tan (15, 881), Boo Junfeng (Sandcastle, Apprentice), Anthony Chen (Ilo Ilo, Wet Season), Kirsten Tan (Pop Aye), and Ken Kwek (Unlucky Plaza, #LookAtMe), among others.

This new generation of filmmakers aren’t just better funded and more technically polished than their predecessors–they’ve proven to be a fearless bunch, willing to explore a broader range of taboo topics (capital punishment, treatment of foreign workers, teenage delinquency, LGBTQ+ issues) in Singapore with rigour and care.

If you’re keen to look back, Singapore’s bountiful cinematic catalogue has never been easier to access, thanks to the Asian Film Archive’s tireless restoration of classics and Netflix’s expansive library of post-renaissance local films. You can even catch screenings of Money No Enough, The Teenage Textbook Movie, Forever Fever, and Mee Pok Man at AFA’s Oldham Theatre this month too.

But if you’re keen to look forward, Singapore’s film industry is financially and creatively well on its way to a second Golden Age—provided that public and government interest doesn’t wane. No art form can better mirror our nation’s fragmented cultural identity than the audiovisual elasticity of film.

It’s why it’s important that we not only strive to preserve our storied cinematic history but continue to pay attention as some of our country’s most talented storytellers continue to reflect the best and worst of our evolving society back at us on the silver screen.

My grandparents helped me understand the Singapore of their youth through classic Malay cinema. Beyond that, local films have continually helped me contextualise our country’s changing mores through my own childhood and adulthood. It would be a shame if we aren’t able to give our children, and theirs, the same gift.