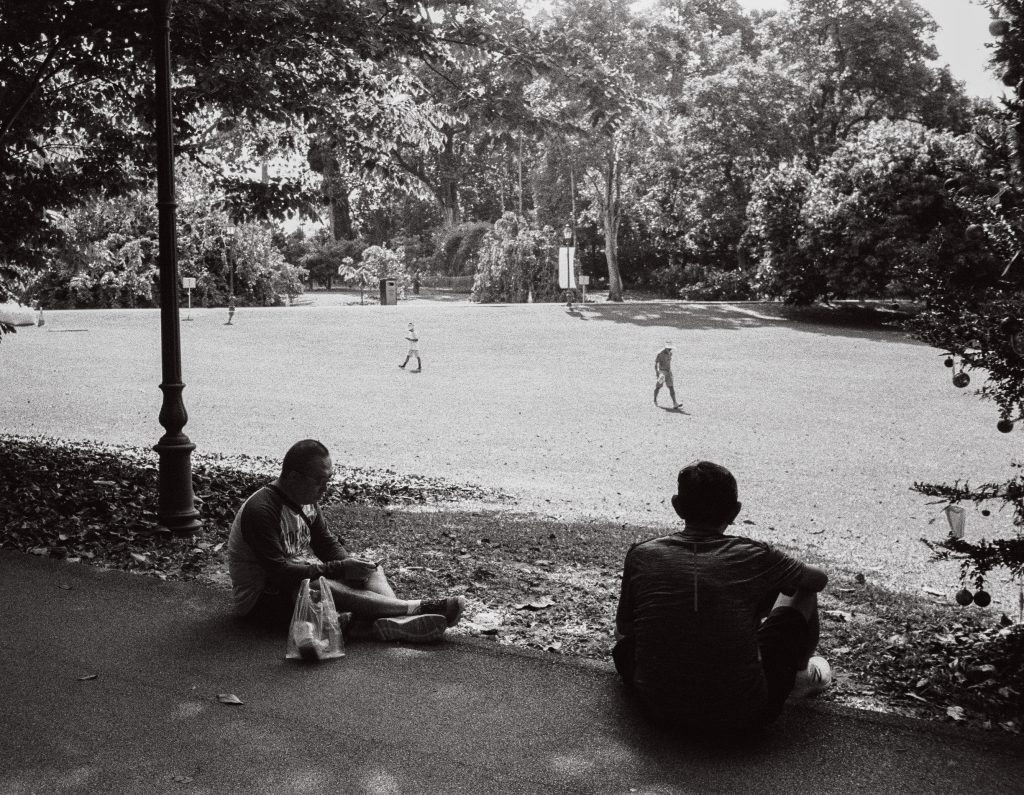

Top image: Zachary Tang / RICE File Photo

The first time I ever stepped foot in a gay club, it was its second night before shutting down for good.

I was 20 years old and barely out of the closet. As is the case for many gay men in Singapore, the two years spent during National Service were a time for self-discovery and trying different ways of being myself before sticking to the items that fit.

My resistance to the idea of downloading dating apps like Grindr, Jack’d, and Tinder at the time meant that I did not have a ton of friends who, like me, were gay. Dating apps were relatively nascent in the early 2010s, much less the normalisation of young men being openly gay.

The grand total of three gay friends that I had at that point had been trying to convince me to go with them to Play Club for nearly half a year. It was a rite of passage, one of them informed me. But as an introvert, I didn’t feel as though I was missing out.

It was only upon the announcement that Play was to close in February 2014 that I finally relented and had my first sip of espresso martini after what must have been an hour-long queue to get into the otherwise nondescript premises of the club, nestled within the historic shophouses along Tanjong Pagar Road.

Of course, the closure of Play did not mean the end for queer nightlife in Singapore. Though Play was the more popular club among younger gay men (which some speculated had a part to play in its closure—how do you make money out of boys in their early 20s who rely on guest lists for free entry and copious amounts of pre-game drinking to avoid having to spend at the club?), the other venues that had preceded Play continued to stand strong.

Revellers who now found themselves adrift were welcomed by locations such as Taboo and Tantric, both of which were located within the 5-minute radius of gay nightlife on the other side of Duxton Hill.

Play, meanwhile, continued to exist in the form of pop-up parties before a short-lived reincarnation as Peaches Club.

In the years that would follow, members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) community would continue to populate Tanjong Pagar’s queer watering holes every weekend, with Dorothy’s Bar along South Bridge Road forming the north bounds of the gayborhood, and various bars, nightclubs, and gay saunas, where gay men could go to cruise, dotting the areas in the southeast quadrant of New Bridge Road and Cross Street.

That is, of course, until the Coronavirus-19 pandemic hit.

Echoes of another pandemic

Queer space in Singapore has always been defined by ephemerality.

Gay men in their 50s would remember the 1990s not only as a time when Mariah Carey, Whitney Houston, and Celine Dion reigned supreme, but also a time of homophobia, both societal and state-sanctioned.

The moral panic surrounding the HIV/AIDS pandemic in the late 1980s and 1990s saw the closure of Niche, one of the first gay discos in the Tanjong Pagar area. There was also the Rascals incident in 1993, widely regarded as Singapore’s Stonewall Riots, in which plainclothes police officers raided a disco on a gay night.

Raids on establishments frequented by gay men were not uncommon by this point, but what was significant about the Rascals Incident was that this time, the patrons fought back by way of a letter of complaint signed by 21 patrons. Surprisingly, the police responded with an apology.

The 90s were also marked by a spate of anti-gay police entrapment operations. These were primarily conducted in gay cruising grounds—spaces that, though technically public, were secluded from public view, such as Tanjong Rhu, one of the more commonly known examples immortalised in Boo Junfeng’s eponymous short film. Plainclothes police officers would conduct sting operations, penetrating territory guarded by nothing but mutual trust and non-verbal codes of consent, with the sole intent of arresting unsuspecting gay men and publishing their mugshots in the state-owned press.

As freshly reclaimed land along the East Coast sat waiting to be mature enough for condominiums and family-friendly recreational buildings to sprout forth, gay men found a safe space for sex and sociality, driven to the literal margins of society, only to have even these spaces infiltrated by the prying eyes of the state.

Finding a rainbow in the shadows

Fortunately, the picture is nowhere as grim these days. While the LGBTQ+ continues to face an array of challenges that emanate from both societal homophobia and intra-group fissures, the government has at least kept good on its promise not to enforce Section 377A.

LGBTQ+ businesses have come and gone for far more mundane reasons that have more to do with the quotidian challenges that businesses face in general.

In an earlier article published by Rice, Singaporean drag queen Becca D’Bus observed that some heavyweights stay for a long time in any nightlife space while many other establishments come and go.

This happens, of course, for a variety of reasons, including low patronage and rising costs, which plagues all sorts of businesses regardless of whether their clientele are mostly queer or straight.

Though it may come as a surprise, queer businesses are permitted in Singapore without much resistance from the government. Queer businesses are, after all, still businesses that bring in tax dollars.

Furthermore, surprising as it might be to some, queer culture is regarded as an asset that positions Singapore as a modern, creative, and global society conducive to tourism and business. Why else would the government allow queer companies and Pink Dot to exist and continually try to convince the international business community that all—regardless of sexual orientation—are welcome to work and live in Singapore?

Indeed, when I visited Dorothy’s for a mid-week kopi-o, my former boss, Rob, told me that there weren’t any business challenges specific to running an LGBTQ+ bar.

“That said, running a gay establishment in Singapore means that it might be best to run silently. The government and conservative pockets of society know we exist. Still, they might prefer not to acknowledge this, so we operate in quiet co-existence with each other,” said the co-owner of the gay bar.

As he poured my kopi-o martini in an old-school kopi cup, my former manager, Jimmy, added that the challenges the business faced had more to do with the bureaucratic Covid-19 safety management measures that were sometimes confusing.

As queer nightlife spaces vanished during the beginning of the pandemic along with other dining establishments, they were among the last to reopen, as bars and nightclubs were generally regarded to be the least essential in society’s reopening.

Nightlife establishments started to reopen after the first circuit breaker, provided that they pivot to restaurant or snacks counter businesses. This process involves multiple hoops and hurdles through various government agencies, which frequently present confusing signals and directives.

Queer people like myself got to enjoy a few months of some semblance of queer community sans intermingling, and I’m grateful I got to turn 27 among my fellow queers at Epiphyte, one of the newer Neil Road entrants. We counted down not to the literal end of 2020, but the final 10.30 pm before 2021 counted for something, at least.

But all did not remain rosy. After the outbreak of the new wave of Covid-19 cases linked to the KTV clusters, nightlife pivots were the hardest hit, regardless of how adherent they had been to the already stringent measures.

Beyond nightlife spaces

Many of us soon found other queer spaces, both online and physical, to find community in light of the closure of the safe spaces that queer nightlife establishments provided.

Some of these spaces existed even before the pandemic, offering the queer community safe spaces that weren’t centred around alcohol consumption and partying, such as established community groups like Pelangi Pride Centre, located in Singapore’s only LGBTQ+ affirming church, Free Community Church.

One young business catering to the LGBTQ+ community well before the pandemic was Prout, a platform for LGBTQ+ people to find queer-run and queer-inclusive meetups, resources, and helplines. In addition to selling merchandise during PinkFest, Singapore’s de facto Pride season, Prout also hosted monthly events such as Queer Trivia Night, run by members who lived in a queer commune known as the Katong Queers.

According to co-founder and chief operations officer Cally Cheung, the organisers of Queer Trivia Night realised that queer individuals still desired to gather physically and have fun in a non-party setting.

“We saw an opportunity for people who would like to connect with others, and we also wanted to educate through fun trivia questions,” said the 26-year-old entrepreneur. “Most importantly, running the events ourselves meant we could keep it accessible to all on most fronts: low ticket prices ($5), easy vibes and welcome to all, community or allies.”

Their Queer Trivia Night went online on Zoom when the pandemic hit, like most other event-based businesses. In place of the already low ticketing price, Prout made the event free for all in the beginning. They wanted to offer more than an alternative, non-party space for queer education and socialisation; some individuals in their community were now stuck at home with their families, some of them in households where coming out was unsafe.

The gayborhood in the time of a pandemic

Like other millennials who moved out of their parents’ homes during the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, I decided to move out just before I was to commence my graduate studies. Don’t get me wrong, my parents are wonderful, and my years spent in the closet culminated anticlimactically with my parents affirming their love and acceptance of me. Nonetheless, it was high time at 26 years old to give myself space to grow as a queer adult.

Though I initially intended to rent a place closer to the university, my prospective housemate and I soon realised that renting in Buona Vista costs around the same as renting downtown.

As two gay men who were both afflicted with main character syndrome, it was a no-brainer for us to decide on a flat in Tanjong Pagar Plaza, right smack in the intersection between one of Singapore’s first public housing projects, the trendy cafes that lined the area, and of course the gay district.

A small part of me had hoped that the pandemic situation would improve and allow me to at least catch a glimmer of what it must be like to live right in the heart of the gayborhood—or at least the closest thing we have in Singapore to a Hell’s Kitchen or Castro equivalent.

And for a while, it did, and I was able to romanticise my walks home from Tantric high on blue spins, when it had to close at 10.30 pm, whether alone or with a lover in tow, blithely ignoring assignment deadlines that loomed ahead.

But I also got to witness firsthand Singapore’s longest-running gay nightclub, also the last one standing, shutter its doors barely a year after undergoing renovation, ironically to expand the available space on its dancefloor. Fortunately, this wasn’t a permanent closure. With no clear end to the pandemic in sight, Taboo had converted into a cafe and relocated to nearby Duxton Hill, a testament to the grit and foresight of its owner, Addie Low.

The collective Home of the Blue Spin, too, more widely referred to as Tantric, has since downsized, going from occupying three shophouses on Neil Road to just one. Though the pandemic has undoubtedly affected all nightlife establishments, the hit that the gay district has taken has felt more palpable.

The vacuum left behind by the reduced perimeters of the gay district has since been filled by new entrants such as ice cream parlour Apiary, cocktail bar Jekyll & Hyde, and Acoustics Coffee Bar. Still, the post-10.30pm silence remains deafening for those who have ever caught a glimpse of the queer vivacity of Neil Road’s shophouses.

And another one gone, and another one gone

In the wake of the pandemic, some queer individuals, myself included, found new queer spaces in non-nightlife establishments, such as bookstores, cafes, and hybrids which positioned themselves as socially conscious establishments that sought to centre the voices of the marginalised.

But as spaces such as these would prove to fail their staff and the communities they claimed to serve, my memories of them became nothing more than line items on my credit card bills.

It can be easy to mistake consumption as a form of cultural participation within the neoliberal paradigm. I buy, I own, I consume; therefore, I am.

But it bears remembering that there is more to queer culture than just businesses. Where queer businesses come and go, subject to the waves of gentrification and recession, it is ultimately people who make up our queer worlds.

As Cally told me, Queer Trivia Night is not a money-making project. “We are not making bank,” she says. “There are still costs involved in running free events sustainably for years.”

“But we continue to do it because it brings the community together in a safe environment where we laugh and learn for a couple of hours. Growing up, I would have given anything to know that these spaces exist.”

Likewise, revealing that their profit margin had taken a significant hit due to the pandemic, Jimmy told me that what keeps Dorothy’s is the importance of preserving what little space is left for the LGBTQ+ community to feel safe and free to be themselves.

“Back before the pandemic, it’s like we are one small kampung, using what little we have to support each other,” Jimmy said.

Rob added, “I set up Dorothy’s to have an inclusive bar for all types of LGBTQ+ people, and it would take me my last breath to have that taken away from me and the community as a whole.”

Indeed, while gay nightlife is not without its exclusions, the first visit is, for many, a rite of passage as they find pockets of safety within this island’s suffocating heteronormativity.

Communion and fellowship start with pre-drinking, maybe at Dorothy’s or one of the Neil Road bars. Then you hop to another bar and bump into a few friends before you all congregate on the dancefloor, DJ or pre-set Spotify playlist at the altar. After service, you might get a free HIV test done at the testing van run by Action for AIDS, or gather in droves at Maxwell Food Centre, too groggy whether from rapture or emotional excess to register the bak chor mee in front of you.

It might seem like it’s just fun, but it’s a ritual of community and respite for many.

When a mainstream bar catering to heterosexual clientele closes down, another one—out of hundreds—bites the dust.

But when a gay bar closes, leaving four behind, its absence is palpable as the loss of a finger on your hand.