All images by the author

All names have been changed

While waiting for my interviewee at the Lembah Subang PPR (Program Perumahan Rakyat) low-cost housing project, I entertain myself by watching two crows snack on a dead rat a few metres from where I stand. The rodent’s bright red insides spill out like fillings from a curry puff. I let my nausea settle down.

The first time I stepped foot into a low-cost flat was some years back in 2018. Billion Dollar Whale by Bradley Hope and Tom Wright, detailing Malaysian fugitive Jho Low’s multi-billion ringgit heist, had just hit bookstores worldwide. That same year, history was made when the Barisan Nasional coalition was defeated by the opposition coalition, Pakatan Harapan.

The Billion Dollar Whale spoke of extravagant parties, luxurious escapades, and lavish homes—all funded unknowingly by Malaysian taxpayers. In stark contrast, the apartment blocks before me look barely inhabitable.

The Scent of Neglect

I am greeted by Meg*, a friendly lady in her 30s who walks me towards the building where she has been living with her mother for the past nine years. She rents her home directly from the government, paying a rental fee of RM124 (S$38.44) a month.

Meg works as a cleaner twice a week at a bank and does freelance cleaning services at several private houses. As her mother’s primary caretaker, having a full-time job is impossible. Meg’s mother holds an OKU card (a person with disabilities) for a psychiatric condition. She also has diabetes on top of kidney issues.

As we step out of the sun and into the sheltered corridor, the blazing heat is replaced by a distinct stench. An odour wafted to my nose—a scent reminiscent of a sewage tank. Meg is unaffected by the smell, so I play it cool.

I can’t tell where the smell is coming from. It could have been the suspicious puddle my foot landed in or the trash scattered everywhere—some unidentifiable. Perhaps it’s the uncovered dumpster nearby. I also remember seeing some soiled rags hanging from an overhead light; it might have been that.

Meg tells me that what I’m seeing is the more spruced-up version of the estate. A week before my visit, some residents here got together to clean the compound. One wonders what it looked like before.

Furthermore, the authorities come pretty regularly to clear out the dumpster. Despite the cleaning efforts, the PPR becomes dirty again almost immediately. Its residents have a habit of throwing their trash straight out of the window—used diapers, rotten eggs, dirty water. It’s probably why the place is so hard to stay clean for long.

The most common ‘flyer’, as Meg calls it, is leftover food, typically curry rice. When the debris hits a parked car, it leaves a brown stain.

Inside a PPR Home

Meg and I wait a while for the only working lift to arrive. There are three lifts, two of which are permanently “under maintenance”.

We were fortunate that day. The only working lift is often unserviceable. When that happens, Meg has to climb the stairs to her unit on the 17th floor—no easy task for someone with asthma.

Meg’s mother does not have the stamina to climb. So whenever the lift breaks down, she stays with Meg’s sister, who lives a short 15-minute drive away at Sunway.

One lift ride later, Meg welcomes me into her humble abode. Peeling wallpaper covers parts of the wall, along with family portraits of various sizes and some Deepavali decorations. In the living room, two rows of sofas are arranged in an L-shape, as if ready for a meeting at any given moment. The cushion covers are stained and yellowed from frequent use.

Meg takes me on a short tour of the house. She shares a room with her mother, while a second bedroom functions as a shrine-slash-store room. She uses the third room to hang her washed laundry. Her clothes went missing the few times she hung them outside.

There’s also a kitchen and one bathroom to share.

Her most prized possession is in the corner of the living room—a flat-screen television. She tells me that burglary is rampant in the building. If you’re away for a few days, there is a chance you’ll come home to find items missing.

The higher the floor, the higher the likelihood of a break-in. The upper floors are less inhabited, making them a much easier target for thieves. The burglars, I learn, usually plot their break-ins in the afternoon when people are at work. Perhaps this is easier than having to tiptoe around a sleeping resident at night.

Meg worries they will take her TV one day because her neighbours have been robbed before. As a precaution, she keeps two guard dogs, Amulu and Jacky—Jacky is a mongrel while Amulu was picked up from the side of a road. “With the dogs, I can sleep peacefully at night.”

Meg is far from overreacting. Where she lives, nothing is safe. Everything here is up for grabs—petrol in your tank, paraphernalia left on the motorcycle, steel in the wall structure. Even doors, railings, and parts of the wall go missing from abandoned units.

“It has always been like that”

Given the rampant breaking and entering, surely the police are a frequent sight here. Meg sighs, exasperated at my remark.

“Every time something happens, we call the police. They send an officer who takes statements and pictures, but nothing happens,” said Meg.

Once, she adds, the police even condescendingly remarked, “PPR sini memang macam tu.” (“PPR apartments has always been like this.”)

Abandoned units with missing (read: stolen) doors play another role: dens for drug addicts. Come dusk, they gather by the stairwell with bongs and lighters.

Meg sees them every now and then. Sometimes, they are as young as 15 or 16, she reveals. And when the addicts get high on drugs, they punch the walls and damage public property.

“When I find myself face to face with someone with glazed-over eyes in the lift, I know they are high on drugs. I exit at the next available floor, even if that’s not where I want to go. I would rather take the stairs.”

The Origins of PPR

The history of PPR goes all the way back to 1982. It was one of several affordable-housing projects introduced by the Malaysian government during the fourth Malaysian plan.

Following the Istanbul Declaration on Human Settlement and Habitat Agenda in 1996—which promotes adequate shelter for all—the government implemented the ‘Zero Squatter by 2005’ policy.

As a result, a deluge of PPRs was built in both west and east Malaysia. There are both high-rise and landed versions of the PPR developments, although the ones in the Klang Valley in the capital city of Kuala Lumpur are between five and 18 floors.

A standard PPR unit hosts three bedrooms, one living room, one kitchen, and two bathrooms. Within the compound of the PPRs are community spaces, prayer rooms, food stalls, a kindergarten, a playground, and facilities for persons with disabilities. However, as I’ve already seen, many of these facilities are poorly maintained.

There are two categories of PPR—rented (like Meg’s) or owned. In East Malaysia, it costs RM35,000 (S$10,565) while in West Malaysia the price hikes up to RM45,000 (S$13,584).

To procure a unit in a PPR, the applicant has to be Malaysian and aged 18 years old and above. Other requirements include having a household income of below RM3,000 (S$905), and having never owned property before.

The good thing about the PPR program is that lower-income groups now have a chance to own a home. The downside is that getting a unit is not easy. Meg’s sister, for instance, has been waiting for four years now. Meg got her unit only because of her mother’s OKU card.

PR1MA: Similar Woes

38-year-old Sara*, who lives in a Petaling Utama 1Malaysia (PR1MA) flat, has similar experiences to Meg’s. Sara hails from Semporna in Sabah but moved to West Malaysia to work in a factory at Port Klang.

She’s a housewife who lives in the PR1MA with her husband and three children. They pay their landlord a monthly rental of RM600 (S$181) for a 3-room, 1-bath unit.

According to the law, owners in Malaysia aren’t allowed to rent out the unit for a certain number of years (much like Singapore’s Minimum Occupation Period). Still, most people ignore the rule without facing consequences.

PR1MA was introduced by the Malaysian government to deliver more affordable homes to middle-income households (supposedly). It is technically not a “low-cost flat” since, by definition, a low-cost flat is priced at RM42,000 (S$12,679) and below.

Meanwhile, PR1MA housing is priced between RM100,000 and RM400,000 (S$30,188 and S$120,753). According to iProperty, the 700 sqft units currently on sale at the Petaling Utama PR1MA are on the market for between RM154,000 and RM190,000 (S$46,490 and S$57,357).

It’s true that, officially, PR1MA is not a low-cost flat. In reality, the housing project differs little from the Lembah Subang PPR. If anything, it just smells better.

Spend ten minutes here, and chances are that you might have already spotted the same kind of litter by now. What used to be a security guard house is now literally a rubbish dump. Most residents don’t pay maintenance fees, so the security service has been revoked.

Drugs and Dead Bodies

Safe to say, PR1MA is a mirror image of the PPR. Unserviceable lift? Check. For five or six years now, in fact. Unfinished meals flying out of the window? Check. Weird objects falling from the higher floors? Check.

Sara shares with me an incident where a resident threw tiles out of their window right above the pathway that kids take on their way to a nearby religious school. People were understandably upset.

Unsurprisingly, like the PPR where Meg lives, public drug consumption is also a severe problem here at PR1MA.

Sometimes, Sara spots fit-looking individuals within the PR1MA compound. Her husband deduced that they were plainclothes policemen who were there to arrest the drug pushers. “I saw a plainclothes police chasing a man one day,” she reveals.

Still, from what I can tell, Sara didn’t seem particularly affected by the drug pushers or the addicts. Perhaps she has gotten used to them.

She remains stoic even as she recounts a murder on the third floor of her block. “The victim’s body was only discovered because of the smell. According to the police, he had been dead for two days. Word on the street is that it was a drug deal gone bad.”

Keeping The Kids Safe

Despite all the challenges living in PR1MA entails, Sara does not consider the situation bleak. For her, the PR1MA estate is where her community is.

A few doors down, her neighbour babysits for her when she needs help. Similarly, her friends cook extra food to share with the community, and she returns the favour when she can. They work together during weddings or other festive celebrations to make the community events a success.

It’s commendable, given the living situation Sara finds herself in. I am not as acquainted with my neighbours as Sara is. The truth is that I don’t even know my neighbours’ names in the condo I live in, where there are ample well-maintained facilities and 24-hour security.

My thoughts momentarily drift to the narrative of the B40 group prevalent in my community. People think they’re miserable people desperate for a lifeline. But that is not the impression I got.

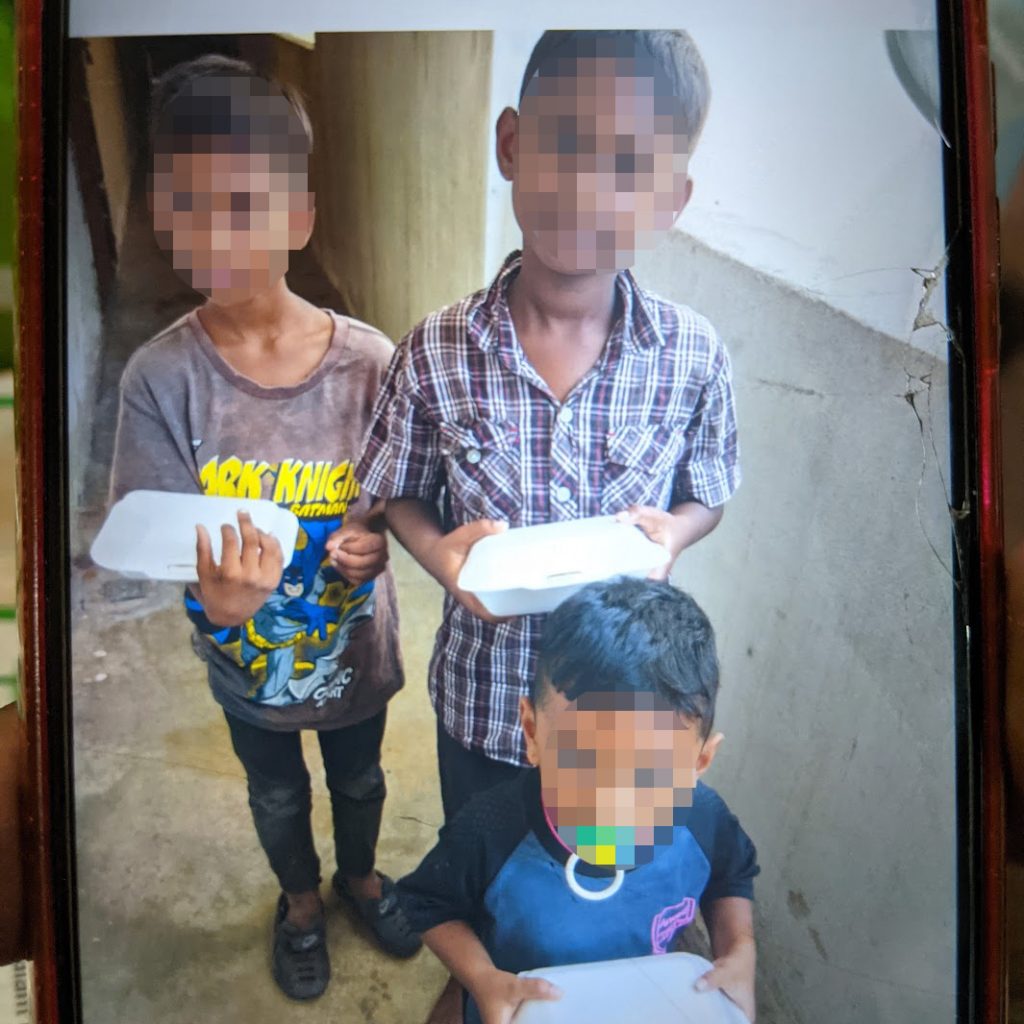

Meg certainly does not see herself as a helpless victim. She regularly participates in charity food drives for the hungry. During the devastating floods that hit several Malaysian states in late December last year and early January this year, she cooked close to 200 packets of food for the victims.

I ask Madam Rita about her thoughts on low-cost housing. A former government school teacher, she is currently the head of a tuition outreach programme for the kids living in Petaling Utama.

Rita, along with other volunteers, has been giving free tuition classes at the community halls near the PPR for eight years.

“It’s a good project, but the ills that come with it are a reality. I know a family whose two sons got into trouble with the law over drugs.”

Parents here worry about the bad influence of the unsavoury characters in the building. So they keep their kids locked indoors to keep them safe. But what this does instead is deprive them of a healthy and active childhood.

“This is what we can afford.”

“Education is key,” Rita asserts when I ask what she thinks is the best way forward. The tuition classes she runs for the children guide them in Mathematics and English. She keeps track of their progress in school too.

Rita makes a good point. For many of the residents, their situations are systemic.

For instance, Sara’s husband is an odd-job worker, which means the family lives strictly within the means of his salary, spending money only on the necessities—food, shelter, water, and the clothes on their back.

Without the extra tuition classes, proper nourishment, and enrichment programmes that their peers enjoy, Sara’s kids will likely fall behind. In a way, they might be doomed to repeat their parents’ lives, creating a cycle never ends.

But with a solid education—whether it be academic learning or more vocational—they could get a better paying job and move into an environment that is far more favourable for their kids in the future. At least, that’s the hope.

But truth be told, attitude matters too, as evidenced by the state of Meg’s PPR just days after the gotong-royong. The behaviour of the PPR and PR1MA residents has to change. Rubbish should go into the rubbish bin, not out of the window, not random empty spaces by the lift. Drugs are bad. So too is stealing.

Still, for Malaysians like Sara, low-cost housing is all they can muster, given their current circumstances. “Ini yang kita mampu.” (“This is what we can afford.”)

I feel that it goes beyond quiet resignation. I sense that she genuinely appreciates having a roof over her head and the community that has made the PR1MA home.

Meg, on her end, has grown tired of hearing people tell her that her PPR flat is not liveable—she’s aware of the pitfalls of staying there. She finds it amusing that well-meaning friends are asking her to move out.

“They’re making such a big fuss over nothing,” she tells me.

I’m not surprised by her reaction. Having only lived in PPR projects, Meg has little to compare to her current living conditions.

“As long as my unit is clean and comfortable, I’m happy.”