Since dining out resumed three weeks ago, the F&B scene hasn’t been celebrating. Rather, it’s been bracing for impact.

Three lockdowns in, each reopening has gotten progressively more muted. Not only are diners not flocking back; businesses have been haemorrhaging money, and many fear what little revenue is trickling back won’t be enough to save them. Cracks in balance sheets have become chasms. After a year and half of start-stops, the next few months will determine who limps on and who bleeds out.

“[This reopening] has been way below expectations and a huge disappointment to the industry,” said Brendon Au of Florian, an Italian restaurant-cum-bar at Naumi Hotel in City Hall. “People will start throwing in the towel in a month’s time if things don’t pick up significantly.”

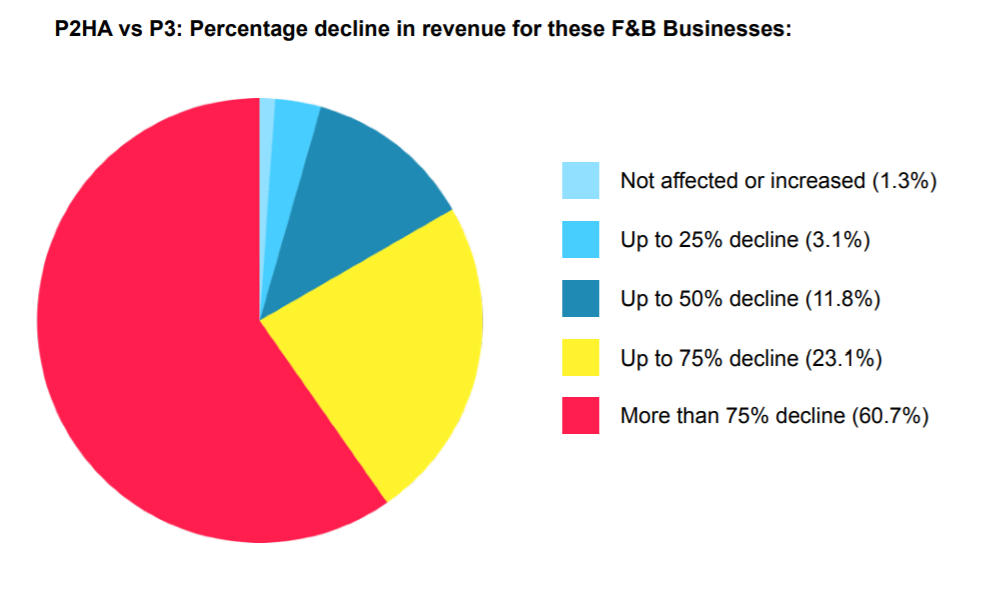

In early August, the SAVEFNBSG coalition, the Singapore Nightlife Business Association (SNBA), and the Singapore Cocktail Bar Association (SCBA) released a joint open letter detailing the results of an informal poll of 639 F&B member businesses, representing just under 2,000 outlets.

The figures are grim: between May to July 2021, 60% of respondents had seen an over 75% drop in revenue. 43% had taken up loans of up to $1.5 million just to fund their day-to-day operations. Around 20% were in the process of winding down, with two-thirds expecting to close in another one to six months if another lockdown takes place.

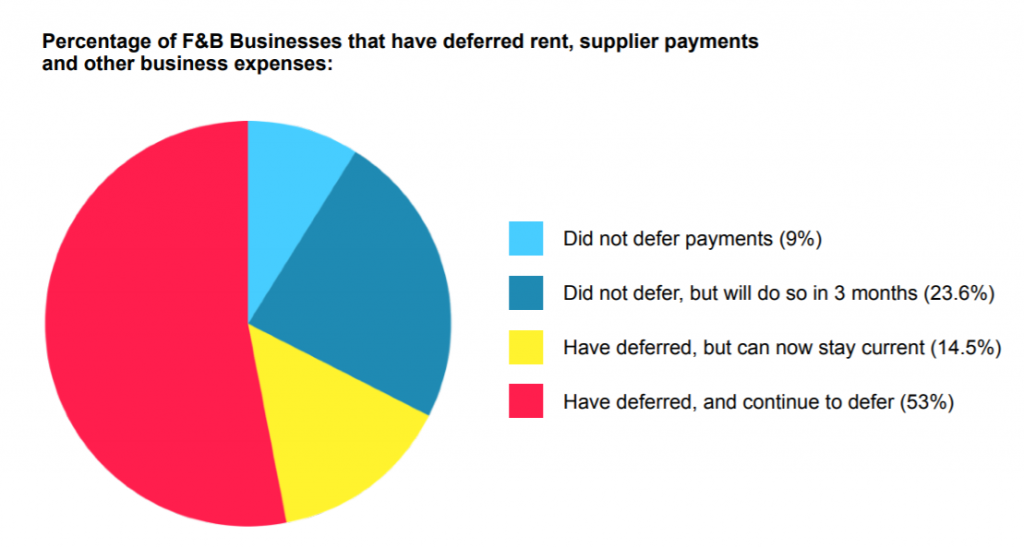

F&B is an exceedingly cash-flow-dependent industry. Running a business in this sector doesn’t just eat money; it gobbles it up. In addition to fixed costs like wages, rent, utilities, and taxes, bills like food costs are often paid to suppliers on credit. Month-to-month, staying afloat requires a delicate financial negotiation, ensuring enough comes in to pay what’s owed as the bills fall due.

Each lockdown smashes this cycle like taking a mallet to an egg. “If you have a whole month of almost no income, you have nothing to pay anyone or anything with,” said Leonard, one of the co-owners of The Brewing Ground in Joo Chiat.

He and his business partners opened the cafe in early 2021, after their other venture, a restaurant at the Esplanade, was badly hit by the restrictions on late-night dining.

“You cannot cover your fixed costs with what you made in HA. It’s impossible. Margins for most restaurants are 7-8%, and if you’re down 80%, it simply can’t be done.”

Thus far, most assistance from the government has come in the form of cost-support measures, primarily the Jobs Support Scheme (JSS) and rental relief or rebates. While all the businesses I spoke to for this piece expressed gratitude for the support received, they were resolute that more help was needed in the correct places—fast.

1. More wage support – and soon.

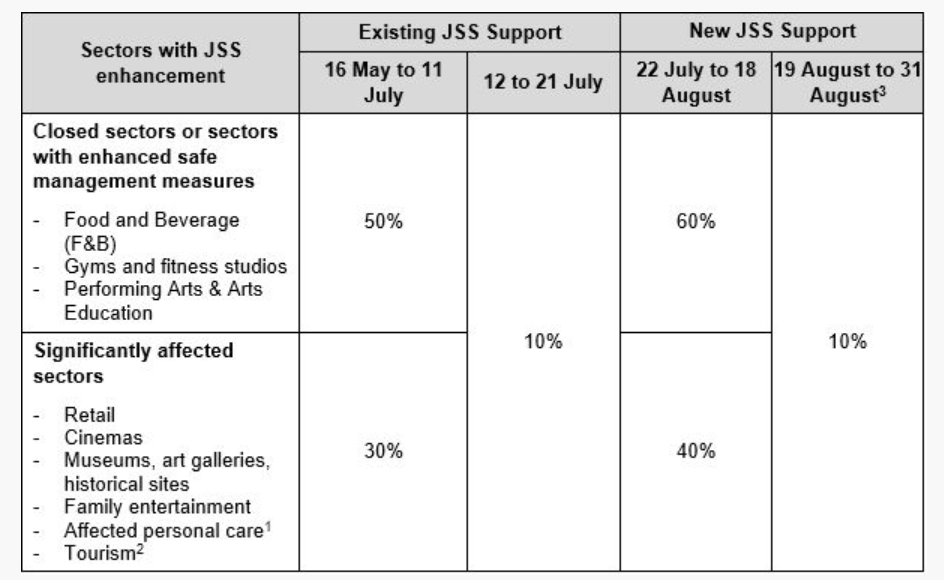

First, wage support and rent relief for May and July, the Heightened Alert periods, has been eclipsed by the fallout from two months of no dining in. Despite the successive disruptions, the amounts were also smaller compared with last year’s circuit breaker.

Last year, F&B outlets had 75% of locals’ wages co-funded by the JSS throughout the circuit breaker, a critical lifeline that helped them ride out the period. This year, however, the JSS was reintroduced at only 50-60% for the affected months, falling immediately to just 10% after.

The drastic withdrawal of support assumes a much stronger, and quicker, recovery than has actually been the case. In stark contrast with last year’s post-circuit-breaker euphoria, this year’s post-Heightened Alert reopenings have been limp, particularly for businesses in the CBD and City Hall areas — which were already reeling from the sustained loss of tourist income.

“The JSS support this time round is insufficient when we are operating in such disruptive conditions,” said Gan Guoyi, the President of the SCBA and a member of the SAVEFNBSG coalition. Nasen Thiagaragan, the CEO of Harry’s and the Vice-President of SNBA, echoed her comments.

“Most F&B businesses continue to face strong headwinds, with slow revenue generation and cash flow deficiency,” he said.

“You cannot cover your fixed costs with what you made in HA. It’s impossible. Margins for most restaurants are 7-8%, and if you’re down 80%, it simply can’t be done.”

Josh, one of Leonard’s co-owners at The Brewing Ground, pointed out that the JSS support, while very helpful, came nowhere close to plugging the gap left by the 60-80% fall in takings for two months.

Moreover, as JSS contributions are calculated based on gross wages (including employee CPF contributions, but excluding employer CPF contributions), businesses’ actual savings decrease after the latter is factored in. “When you consider [employers’] CPF, employers only get a rough 30% saving, despite a 50% JSS,” noted Brendon.

The pay-first-reimburse-later model of the JSS further means that for many SMEs, what help there is might come too late. The industry’s reliance on cash flow makes the timing of cash injections as critical as the quantum.

While stressing that the support was appreciated, Dylan Ong, owner of The Masses, likened the situation to “sending water only after your house has burned down”.

In light of all this, the SAVEFNBSG coalition has recommended that this year’s tranche of enhanced JSS payouts, which are currently slated for disbursement in September and December, should be consolidated and brought forward. The coalition has also proposed a deferral of principal bridging loan repayments till 2022.

“Business in post-Covid times has been nothing like pre-Covid times,” said Josh. “Cash flow is key. You can’t just say, ‘JSS coming in the third quarter’. When F&B says they need help now, they mean they need help now.”

2. Extend wage support to foreign staff.

All the businesses interviewed for this story highlighted a major omission of the JSS: it does not apply to foreign staff, who are widely acknowledged to form the backbone of the F&B workforce.

Due to low interest amongst local workers, the F&B industry relies heavily on foreign staff to make up its manpower needs. Since the pandemic, the unequal JSS support has made them even more expensive to hire and retain, on top of existing measures like the foreign worker levy.

Leonard gave an example to illustrate the maths. “Say, in a typical scenario, Singaporeans and Malaysians get S$2,000 each. Under a 50% JSS, you get back S$1,000 for the Singaporean’s pay. For the Malaysian worker, you not only pay the full salary, but an additional S$800 for the levy. So that’s $2,800 in all.”

Increases to the local qualifying salary, or the minimum salary local workers must be paid before a business can hire foreign staff, have also pushed up overall labour costs.

“How much is 10% [of local workers’ wages] going to do for any restaurant?”, said Dylan, referring to the abrupt fall in JSS support once dining-in resumed. His team at The Masses is composed of around 60% foreign staff. “Aren’t foreigners a part of our workforce too?”

Business owners themselves are loath to put foreign staff on no-pay leave, seeing it as an option of last resort. “It’s a double whammy. They have rent and other living costs, so if they are put on no-pay leave they cannot survive,” said Brendon.

Ms Gan of the SCBA noted that last year’s Foreign Worker Levy Rebate, implemented as part of the Solidarity Budget, was not reintroduced this year. In July, the SAVEFNBSG coalition called for the JSS to be applied to all employees, regardless of nationality, and extended to September rather than mid-August.

“Aside from being away from their families, living abroad means their livelihood expenses are potentially higher. We understand that the government would like F&B businesses to provide jobs to locals, but the struggle to hire locals who are willing to join our industry full-time has and continues to be a challenge,” she said.

3. Mandate and enforce rent relief, especially amongst private landlords.

Similarly, many businesses were disappointed by this year’s rent relief, especially the reduced amounts and the absence of measures to compel landlords’ compliance.

This year, F&B outlets were eligible for two weeks to one month’s rent relief for both Heightened Alert periods. (Hawkers in NEA-owned hawker centres have received full rebates.)

However, many feel more could be done, relative to both the scale of this year’s losses, the compounded financial strain, and the particular burden rent obligations place on operating costs.

In 2020, businesses were given four months’ rent relief.

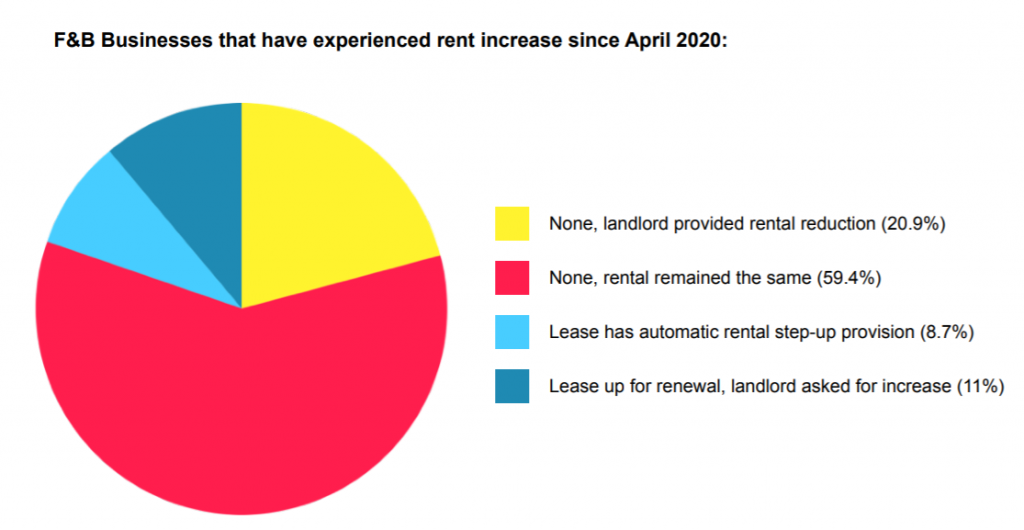

Ms Gan drew attention to how the reliefs are far outstripped by the extent of business’ struggles. “Based on the survey, 70% of respondents requested a deferment of rent or debt repayments. 60% have not received any rent reduction,” she said, highlighting that 20% of respondents’ landlords had in fact raised the rent since April last year.

Unlike the 2020 reliefs, which were enshrined in the COVID-19 (Temporary Measures) (Amendment) Act, this year’s reliefs have not been legally mandated. “[As such], businesses remain unsure of when landlords will honour the waiver,” she added.

Her concerns were echoed by nearly all the businesses I spoke to. There was general confusion over when rebates will arrive, whether they are automatic, and whether private landlords will comply.

“We’re not sure. We haven’t gotten ours yet,” said Josh. The Brewing Ground sublets part of a compound owned by the Singapore Land Authority, which would make them eligible for a full rebate as a tenant of a government-leased property. As of publication time, while their landlord had been in touch to verify their SME status, they had yet to hear directly from the SLA.

“If it’s taking this long, I can only imagine how long it might be with a private landlord,” he added. In late July, the Ministry of Finance stated it was ‘looking to require’ sharing of rent obligations between the government, landlords, and tenants.

“People are running out of steam, and the government is running out of bullets.”

Rent has long been a chief concern of F&B businesses. According to Brendon, rent amounted to around 25% of Florian’s operating costs pre-pandemic. By his estimate, this has now swelled to 40-50%. Although he had not had issues with his own landlord, he had heard of many instances where other landlords refused to act without a legal mandate.

“Cost savings have reached a limit of sorts unless landlords play their part, with enforcement by the government,” he said. In his opinion, landlords have not fully grasped the damage that could be caused by a hollowing out of the industry and a deterioration in landlord-tenant relationships.

“In the short term, as businesses shutter and F&B workers start to change industry, landlords start to lose tenants. [Perhaps] they think it’s okay and people will come back when the economy recovers,” he said. “But I think COVID has irrevocably changed the business community’s sentiments towards landlords.”

4. Suppliers and manufacturers: the neglected players in the ecosystem

Meanwhile, since the very start of the pandemic, one key group of the F&B ecosystem has been entirely overlooked: supplies and manufacturers.

Such businesses are a vital, if often invisible, part of the industry—the arteries connecting restaurants to the very food they cook. However, they have not been eligible for any of the enhanced support provided to customer-facing F&B outlets even since the circuit-breaker was enacted.

“To be honest, we feel very disappointed and jaded that whenever enhanced measures for F&B have been announced, suppliers and manufacturers have been left out,” said John Wei, the founder of Brewlander, a local brewery and alcoholic beverage supplier.

“We’ve been voicing this out since the start. We should be recognised as part of F&B too.”

“If you take us [suppliers] out of the equation, restaurants can’t operate,” he said, highlighting the symbiotic relationship between the two. “We are directly affected by a restaurant’s productivity and operations. If they can only do take-away and their revenue drops 50%, that obviously affects us.”

Suppliers’ problems are as varied as they are hidden. Like restaurants, many were left scrambling by the start-stops, with many forced to discard or give away thousands of dollars’ worth of perishable stock.

Meanwhile, spiking costs added to their woes. For years, ingredient costs were already highly volatile due to changing global demand and the climate crisis. Then the pandemic drastically increased air freight prices.

“What might have been a dollar became $5,” said Sebastian Teow, the director of Lim Joo Huat. His company supplies businesses across all segments of the F&B industry, from high-end joints like Burnt Ends to hawkers.

“We had to try and absorb some of this, because restaurants are also struggling. If you increase prices too much they also cannot buy, or someone else will come in with a better price. The race to the bottom just continues,” he said.

To keep business relationships going, his company has extended some of its credit terms from 30 to 60 days, but the company can only shoulder so much risk. Should too many clients shutter, the business would be saddled with bad debt.

“Restaurants have cash flow problems, but this affects our liquidity too. We have very high credit exposure but little cushioning,” said Sebastian. “We’re kind of on our own, suffering in silence.”

Ms. Gan of the SCBA agreed. “When we [restaurants] are at a standstill, they are at a standstill,” she said, noting that restaurants could at least rely on online delivery and take-away, unlike B2B services.

Meanwhile, the enhanced rent relief and wage support has not been extended to these businesses. For example, as the Heightened Alert rent rebates only applied to businesses leasing commercial premises, F&B manufacturers in industrial spaces were not covered—notwithstanding that their licence conditions allow them to only operate in specific approved zones.

John shared the results of a survey conducted by the Singapore Craft Beer Steering Committee, a collective of businesses in the alco-brew sector, in late July. Similar to the SAVEFNBSG poll, the results were dire: 63% of respondents had had to dip into personal funds to keep going, and around 68% gave themselves one to six months before being forced to close.

The letter calls for rent relief and JSS support to be extended to suppliers and manufacturers in the alco-brew sector. In particular, it notes that manufacturers’ Singapore Standard Industrial Classification (SSIC) codes, which are used by IRAS to determine eligibility for reliefs, should be included in the list of qualifying sectors—an administrative issue with far-ranging consequences.

John pointed to the irony of letting businesses fail at a time when local entrepreneurship and brand-building is being championed. Moreover, the potential decimation of the alco-beverage industry would be especially sad, he observed, given how much it has grown in recent years.

Today, there are at least 16 local breweries and over 30 local brands in the sector.

“The last few years have been such an exciting time, but if half of us don’t survive or feel it’s too much and just want to throw in the towel, the growth of the last 3 years will have vanished,” he lamented. “It would be a shame if half of us don’t survive just because we got overlooked.”

5. The problem with no solution: How to get bodies back into restaurants.

The pandemic has hammered the F&B industry on too many fronts to count. The financial arithmetic explored by this article is just the beginning; there’s the operational and logistical toll of navigating ever-changing venue capacity rules and vaccination checks, not to mention the psychological strain of trying to keep a business alive in these times.

From the exorbitant commission charged by delivery apps—which some interviewees described as ‘sharks’—to gripes like the reduced opening hours and ban on playing background music, little things add up. And while all the businesses I spoke to acknowledged the help given so far with grace, their desperation for the authorities to do more, and do better in communicating with people on the ground, was evident.

“We wish to reiterate that we appreciate what the government has been doing to support the F&B industry,” said Ms Gan of the SCBA, noting that ‘unprecedented’ measures had been put in place for these ‘unprecedented’ times.

“That said, we do want to ask for a more collaborative approach—through proactive and open dialogue—when it comes to introducing both support and restrictive measures that impact our industry,” she continued.

Nonetheless, one vital aspect of restaurants’ survival remains uncertain: how to get people eating out again.

“Everyone is appreciative of the help so far, but the huge drop in revenue needs to be solved ASAP, and not just focused on finding ways to cut costs. Unfortunately, what no-one knows is how to bring diners back,” said Brendon.

“The conversations and dialogues with the authorities have helped for sure. But to be honest, people are running out of steam, and the government is running out of bullets.”

Living with the hand we’re dealt

It was a gnawing fear shared by all the restaurants I spoke to, even if no one could pinpoint the cause—the pandemic reshaping our eating and spending habits, re-entry anxiety, or the cumulative exhaustion of the 1.5 years finally eroding the novelty of eating out.

Unlike legally mandating landlords’ rent relief obligations, or boosting wage support, it’s not a problem that can be solved via regulation or throwing money at the problem.

But without customers to serve, there’s simply no way restaurants—and the suppliers and manufacturers all holding each other up—can keep going.

It remains too early to see what the full impact of the pandemic on Singapore’s F&B scene will be: forced trauma surgery, or an extinction event. For now, businesses are watching the clock, hoping enough diners will come back before the money runs out.

“It’s been really emotionally draining,” said Josh. “We just have to live with the hand we’re dealt, but we haven’t seen the full impact of things yet. No one has credit now, and things will start to bite in about a month. They could get a lot worse before we see if they get better.”