It’s become fashionable these days in Singapore media to talk about the importance of mental health, as tensions surrounding the pandemic have led Singaporeans to pay greater attention to their emotional wellbeing and to practice self-care.

On balance, this trend is overwhelmingly positive. What was once stigmatised in Singapore’s resilience-obsessed and achievement-oriented culture is now being openly talked about.

But mental health is also a deeply personal issue, where experiences vary widely. Hence, in reporting on mental health, there’s always the risk of oversimplifying a complex topic. For journalists with deadlines to meet, it becomes tempting to draw direct causal relationships between current events and the ‘trending’ topic of mental health — without acknowledging the uncertainties inherent in the subject.

The past few months in Singapore have been an interesting case study.

Since May 2021, mental health has been invoked for a litany of recent incidents, including: racism, anti-maskers, work culture, suicides, the River Valley High School murder, Joseph Schooling, and the pressures faced by Team Singapore athletes.

While such stories are well-intentioned, how useful are they in moving the conversation forward?

And at what point do these types of narratives do more harm than good?

Mental Health Shouldn’t Be Used to Justify Bad Behaviour

Two successive Phase 2 (HA) has exacerbated existing fault lines within Singaporean society, placing troubled individuals in the media spotlight.

Examples of this include Beow Tan, the anti-mask MBS lady, and Benjamin Glynn, the anti-mask expat, who gave us one of the most bizarre courtroom rants in recent memory.

In such cases, the online discourse is inevitably steered toward mental health and the pressures we all face in pandemic. In cases where direct speculation by a journalist is too risky, an expert is interviewed so that the speculation can be done by proxy.

This, to me, feels like projection. While mental illness may partly explain their bizarre behaviour, it is unlikely to be the whole story. In any case, it is simply premature to engage in this sort of speculation, before a psychiatric evaluation is even conducted.

It is concerning how quickly a complex topic such as mental health is being invoked — to the point where I start to question whether enough nuance has been injected into the conversation.

If a convenient mental health narrative can be published to explain everything, how useful is this narrative in furthering the discourse?

What’s more, by drawing connections between mental health and the most eccentric behaviours we see in public, it only further stigmatises the issue and prevents people with mental health conditions from seeking help.

This is a matter of public education, an issue that Porsche Poh, executive director of mental health non-profit organisation Silver Ribbon, feels strongly about.

While she has observed some improvement in how the local media has covered mental health issues, there is still more work to be done in clearing up misconceptions the public may have on the subject.

“If it is not being reported responsibly, I am worried that some people with limited info on mental health might poke fun or shame these individuals on social media, or start stereotyping other people with mental health conditions,” Ms. Poh explained.

“As a result, this will make it more challenging for those at-risk to come forward to seek early treatment, as well as for those who have defaulted on their treatment to resume treatment — for fear of being shunned by their relatives and friends.”

How the broken incentives of media creates a toxic environment

Two recent incidents, for me, highlight the disconnect between what the media preaches about mental health and what it actually does in practice:

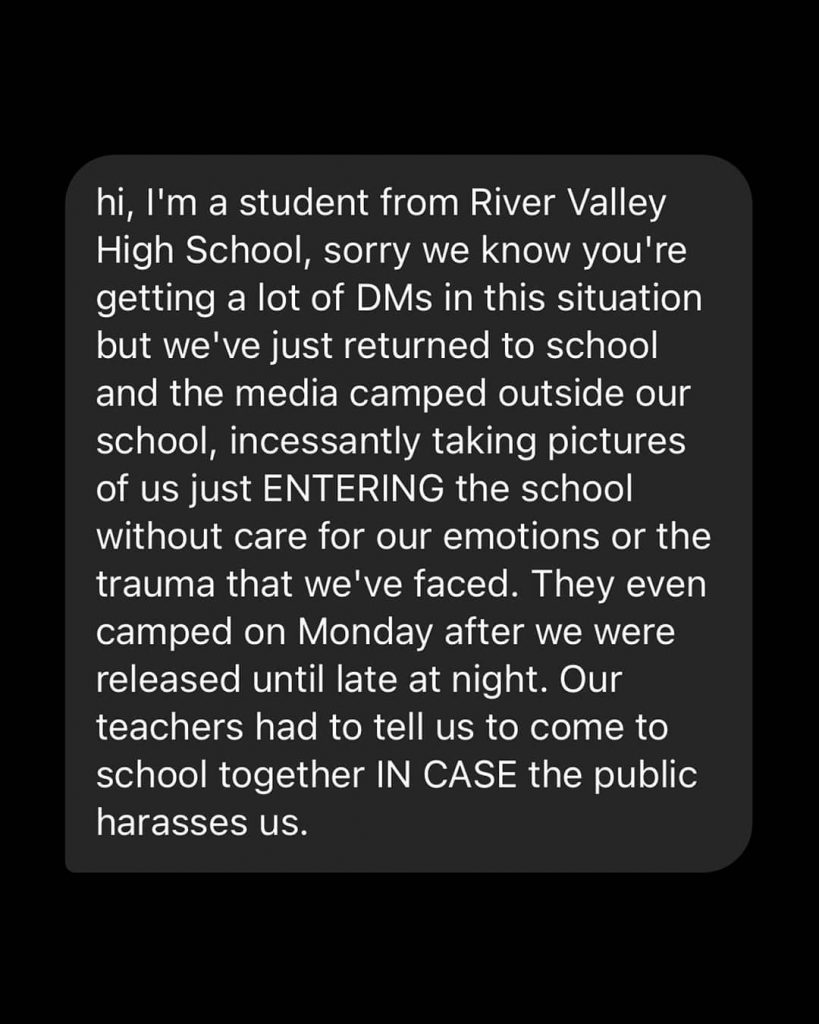

1. Reporters and photographers camping outside River Valley High School in the hopes of interviewing students

2. The post-race interview conducted with Joseph Schooling after his disappointing finish in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

The first screenshot is self-explanatory. It’s ironic that while subsequent commentaries will be written on how we should give RV students the space to heal, the media, by the nature of their job, is unable to follow its own advice.

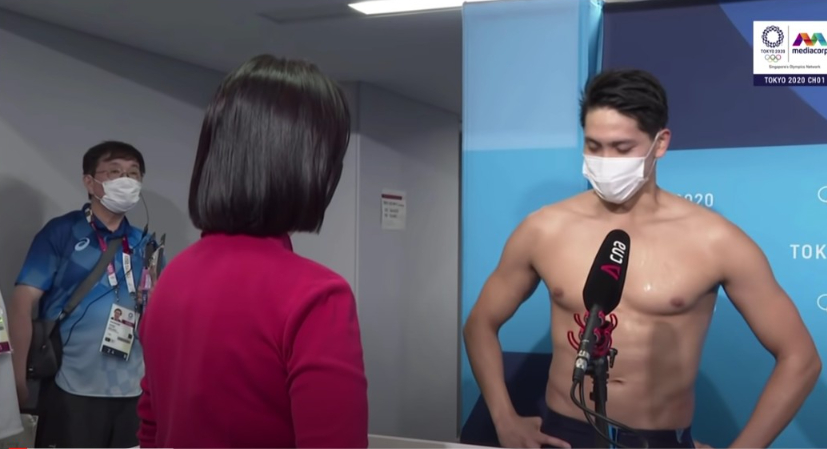

I felt a similar way when watching the post-race interview with Joseph Schooling after he finished 44th out of 55 in the 100m butterfly in the Tokyo Olympics.

Schooling, still breathless from the race and devastated by the result, was paraded in front of lights and cameras and forced to give his immediate reaction to what I can only imagine is a setback in his celebrated career.

The maturity Schooling displayed in his response was remarkable. His ability to acknowledge his disappointment, while not allowing the results to completely define his efforts, is what truly makes him an inspiration and national champion.

For what it’s worth, I also thought the questions posed by the local media interviewer were fair and open-ended.

Both the athlete and the journalist were just doing their jobs — the best way they knew how.

And yet, the situation itself still felt vaguely exploitative. One wonders why the interview could not have taken place after Schooling had been given more time to process the result. Time to reflect, to consult with his coaches — or even to shower and change.

In many ways, the Schooling situation is reminiscent of the broader mental health debate going on in sports today. When athletes like Naomi Osaka and Simone Biles raise the issue of mental health, the media are often the primary culprits.

Oftentimes, it’s the media that create the high expectations and pressurised environments that set up athletes to fail. For example, local journalists were the ones who latched onto the issue of Schooling’s weight during the 2019 SEA Games, engaging in speculation on what this means for his chances at the Tokyo Olympics.

To then turn around in 2021 to ‘raise awareness’ on the pressures faced by athletes is a bit like asking your drug dealer for rehab advice.

This goes back to a structural issue with today’s attention economy. Social media has turned journalism into a 24/7 game. The relationship between the media, the narratives they create, and the mental health impact of those narratives is often incestuous and self-reinforcing.

And with 80% of advertising revenues flowing through Google and Facebook, there is every incentive for the media to play this game for eyeballs and clicks. To latch onto ‘trending’ topics without regard for nuance or consequence. To pursue short-term relevance over long-term insight.

Ultimately, it is unclear where the responsibility for this problem lies: is it the media’s duty to avoid pandering to our baser instincts for sensationalism?

Or is the media just providing the public with the easy answers and comfortable narratives they’re looking for?

A veteran journalist weighs in

To get an insider’s perspective on local media, I approached veteran journalist P. N. Balji, former Editor-in-Chief of Today and author of the insightful book Reluctant Editor, to get his thoughts on how the media has handled recent events like the RVHS incident.

His overall view is that we should cut the media some slack, since like everyone else, journalists are operating in uncharted territory.

“There is really no right and wrong way to cover incidents like River Valley,” he said. “The decisions made also depend on how mature our society has become.”

He did, however, leave me with a list of dos and don’ts:

1. Don’t speculate. Stick to the facts.

2. The use of photos is very sensitive. Use them only if identity becomes an issue. Eg. if an alleged killer has escaped and the police are seeking the public’s help.

3. Do give the families space to mourn. Don’t take on the role of paparazzi.

That being said, Balji believes that the local media has been fairly responsible in their coverage, and that we should not take the media to task for being outside the school with their mobile phone cameras.

“We must be careful about overkill,” he said ”Don’t criticise the media for errors of judgment here and there. We have to look at the bigger picture.”

And what exactly is this bigger picture?

For Balji, it’s the pursuit of the more impactful story.

“[As journalists], a scoop is not what you should be looking for,” he said. “You should be doing background work today which can be used for a more substantial story later on.”

“It is that story that will ultimately be remembered.”

The media can do better to acknowledge uncertainty

In 2020, Singapore reported 452 suicides. The highest since 2012. But behind every statistic, there are numerous individual stories and experiences that have a far-reaching impact on families and even entire communities. The lessons to be learned from each experience transcend the limitations of the generic commentary and expert interview.

Truly impactful stories take time. To believe otherwise, we run the risk of explaining away complexity with boilerplate narratives, tying up loose ends to conversations that should have remained open.

For the media’s part, this means better editorial discretion on what not to publish. Deciding which angles not to take. To give stories more time to take shape. This requires an almost ascetic editorial discipline, and it runs contrary to every economic incentive in our attention economy.

But the stakes are high. This is not a partisan issue, nor is it a problem unique to Singapore. But like other institutions reckoning with the new normal, it’s okay for the media to admit that their voice is no longer authoritative, that journalists do not have all the answers, and there is still considerable room for improvement.

Perhaps the best response to the RVHS incident was from PM Lee Hsien Loong, who offered his condolences just days after the tragedy.

“We cannot make sense of what happened,” he said. “Words fail us because we cannot understand.”

This doesn’t mean that nothing more can be done. It’s simply an acknowledgement that the wounds are still fresh, and that for meaningful change to happen, we must first give each other some room to breathe.