All images by Wu Bingyu (@bingleswu).

A couple of months ago, I read that ACRES, the wildlife protection charity, has been fielding more calls to its 24-hour hotline than ever. Their rescue team was kind enough to let me tag along on two of their shifts, which is how I ended up on—literally—the wildest assignment of my career.

PART ONE: DAY SHIFT

0945: Mayhem

In a van somewhere on the KJE, chaos reigns.

To my right, Kalai, ACRES’ co-CEO, is driving with the grim expression of a man in need of caffeine. To my left, Laurie, his partner for today’s shift, is triaging calls to their hotline, toggling between phones (one for ACRES’ case logs, one for the hotline) like she’s competing in the multi-tasking Olympics. From what I can tell, she’s talking to a caller about two boar piglets trapped in a drain, sending another Voice Notes about an injured bird, and identifying animals from a never-ending stream of incoming photos, all at the same time. The sheer volume of messages is giving me secondhand anxiety.

We are on our way to retrieve a python from somewhere in Sembawang. In the back, Bing, my photographer, is camped out next to two more pythons in their carriers, picked up by the team on last night’s shift. It’s like a scene from an ambulance in a medical drama, except that instead of defibrillators and stretchers, there are gunnysacks and rope and the patients are cold-blooded.

Meanwhile, the phone doesn’t stop ringing. When Laurie pauses for breath after finishing a Voice Note (“I know it looks scary comma. Baby birds like the dark full stop. It will be good if you can put it in a box with some ventilation full stop.”), I take the chance to squeeze in a question. Are humans or animals the more challenging part of the job?

“Humans,” she says, without looking up from the phone. “Do you even have to ask?!” adds Kalai. He steps on the gas.

1015: First snake of the day

Our first rescue is at a construction site, where the workers have called in about a python buried under a mass of wood debris. Kalai and Laurie rummage through the mound, searching for the snake, but it’s in too deep. They’ll need to take a risk and get the excavator to dislodge the heaviest pieces of wood before they can reach it.

It works. Five minutes later, they’re pulling out a 3-metre-long python.

The men gather round, filming everything on their phones.

After the python is safely transferred to a carrier, Kalai asks the onlookers if they have any questions. He’s met with silence until one tentatively asks if it’s an adult.

“By local standards, yes,” says Kalai. He delivers a short nature lesson: snakes are often found at construction sites as they like being near water, and drainage systems are usually the first things to be set up. This python probably slunk over from a nearby canal.

Back in the van, I remark that the men seemed more fascinated than anything else. “Yeah, they were quite chill about it,” says Kalai. In his experience at ACRES, whenever the team gets construction site calls, attitudes to snakes vary with the workers’ cultures. Men from India, like this morning’s caller, are usually either terrified or awestruck because snakes are revered in Hindu mythology. Had its finders been Thai or Vietnamese, the python might not have been so lucky.

1100: Much ado about nothing

We make a quick stopover at the zoo to hand the pythons to Wildlife Reserves Singapore, whose herpetologists will microchip the reptiles and release them. Before Bing can cheer the extra legroom, a call comes in for another snake at Upper Bukit Timah.

We arrive at the location—a disused school compound—to find that someone has trapped the snake in an empty soda bottle. It’s a tiny wolf snake, no more than 30 or 40cm long, and so delicate that a too-firm touch would snap its back like a toothpick.

Laurie suggests I try handling the snake, so I pull on a pair of gloves and awkwardly manoeuvre it into a small bag, trying not to drop or crush it. A cleaning lady hovers at a distance, watching. She frantically shakes her head when Laurie asks if she’d like a closer look.

On our way out, the security guards are full of questions for Laurie. Is the snake poisonous? Are there more of them?

Frankly, Bing and I are puzzled by all the fuss. Couldn’t someone have released the snake, since they went to the trouble of trapping it already, or just left it alone, to begin with? After all, there’s barely anyone around, the compound is massive, and the snake is tiny. I’m surprised the staff even noticed it.

Laurie shrugs. “Snakes get a bad rep,” she says, once she’s done reassuring the guards and allaying their fears. Although very few local snakes are venomous enough to be dangerous, most people don’t know that, and nobody wants to chance it.

1215: In transit

En route to our next stop, I take the chance to chat with Laurie, now that the calls have slowed somewhat. She’s been volunteering with ACRES for about three years and has seen all sorts of calls and callers.

1. Bird calls are mostly about sick or injured animals. Often, people try to keep the birds on their own for a couple of days, feeding them with rice before giving up and calling for help when they don’t improve. She strongly discourages this. A bird that’s gotten too used to human contact, especially if it’s young, will find it harder to re-integrate in the wild. Also, birds do not eat rice.

2. Calls regarding ‘conflict animals’, like monkeys, snakes, and bats, are where things get tricky. Most of these callers tend to live around the central catchment area, leading to a higher frequency of animal incursions. Although warnings have been around for years, most people aren’t mentally—or practically—prepared to deal with macaques eating their unattended breakfasts or rummaging through their bins.

3. Otter PR is on the way down, now that people are starting to realise they’re not cuddly little critters, but menaces who will happily polish off your prize koi and leave the mangled corpse as a tip.

4. Meanwhile, the callers themselves fall into several camps. A handful is psychotic, like the woman who demanded they chop down all the trees outside her house because of a squirrel, or the man who called his town council every day for two years over a chicken. Some have a saviour complex and react badly to being told their efforts aren’t helping. But most people, while well-meaning, are anxious, concerned, or clueless.

I can sympathize with the cluelessness. Although the area I live in has a fair amount of wildlife— I’ve seen hornbills, bats, and civet cats in the garden—I’ve never paid much attention to them, let alone acknowledged them as neighbours.

The ‘concrete jungle’ narrative, much as it reflects visual reality,

obscures the fact that Singapore is also home to many wild animals.

And animals do not simply stay in the reserves we’ve ‘designated’ for them.

“[People seem to have] this blind spot around the reserve, as though there’s a magical border which the animals will stay within. This simply isn’t true,” Laurie remarks. As the rising number of wild boar encounters shows, animals go where they will in search of food and shelter. Thanks to rampant development, this is, increasingly, where humans are.

But unlike, say, Australia, where people recognise snakes as part of the landscape and know what to do if they encounter one, Singaporeans simply don’t expect to deal with wildlife.

As sheltered city-dwellers, we often assume they don’t exist, fail to notice them or expect them to function on our terms—which is precisely the opposite of how nature works.

1245: Starling rescue

A family has called about a baby starling that rolled off the roof and landed in their backyard. It’s so weak that Laurie doesn’t dare feed it in case it chokes.

Kalai lays out the options for the family, who seem genuinely concerned about the bird’s welfare: 1. Return it to the roof and see if its parents come back for it, or 2. Let ACRES take the bird, though there’s a chance it could deteriorate further before we can take it back to the shelter and get it seen to. (The shelter, for that matter, is almost at capacity; ACRES receives calls for many more birds than they can take.)

“Either way, nature might take its course, but we prefer to try and reunite where we can,” he says. The family agrees to give it a go, so Laurie fashions a makeshift nest out of a flower pot and some twigs transfers the starling to it, and levers the contraption out of the bathroom window. Everyone crosses their fingers that the parents will return.

On our way out, Kalai and Laurie thank the family for their help and for looking out for the bird. “It’s no problem, we love nature,” says the mother.

According to her, both starlings and doves have been nesting in the roof for a long time; in the mornings, they often wake to find seeds scattered all over the backyard. Nonetheless, they seem quite sanguine about the mess.

“Such inconsiderate tenants,” jokes Laurie.

1400: Lunch

Humans need care and feeding, too.

1530: Monitor lizard (I)

After lunch, we battle our food comas to go retrieve a monitor lizard in Queensway. It wandered into someone’s fishpond in search of lunch, got trapped, and ends up splashing water all over Kalai’s trousers while he wrestles it into a carrier.

“You mean they can swim?!?!?!” wails the horrified caller.

Her five-year-old son, on the other hand, is all too keen to get a closer look at the lizard, which is hissing furiously after being penned up. Bing and I explain that no, he shouldn’t try to pet it, and no, it is not a Komodo dragon.

Singaporeans simply don’t expect to deal with wildlife.

We often assume they don’t exist, fail to notice them,

or expect them to function on our terms

— which is precisely the opposite of how nature works.

1530: More birds and monitor lizard (II)

From there, most of the rescues are uneventful. We collect a baby dove from a condo, stop off at RJC for a pink-necked green pigeon fledgling, and retrieve another monitor lizard from a supermarket in Little India.

When we get there, we find that the store’s staff have also called the police, so there are eight people crammed into a tiny room over one small reptile. The overreaction strikes me as ridiculous, but ACRES and the police take it in their stride. We’re in and out with the lizard in ten minutes.

Still, I can’t help but wonder how much time and resources get wasted on calls like this one, or the morning’s wolf snake. Ignorance begets irrationality. If ever there was a reason for better nature education, this is it.

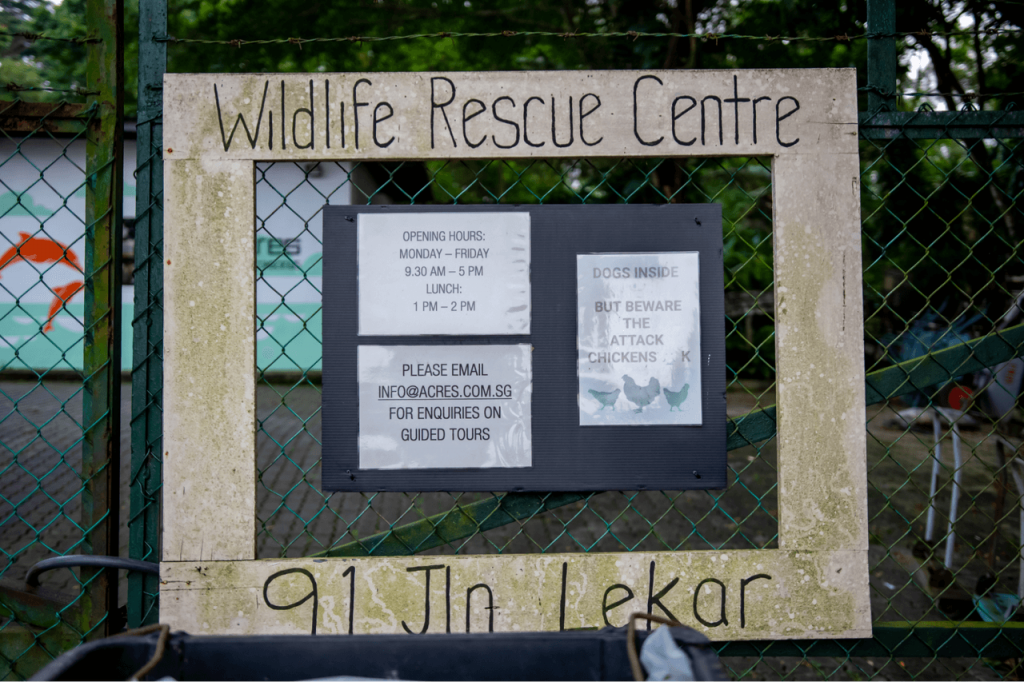

1900: Back to HQ

By the time we finish our final call for the day—a poisoned pigeon in Whampoa— it’s almost dinnertime, so we decide to head back to ACRES HQ. First, however, the day’s rescues need to be unloaded, fed, and settled in the rehabilitation centre.

Meanwhile, the phone is still going in the background. Calls peak in the morning and evening, when most human-animal encounters take place. The night shift will respond to these and whatever comes in in the next few hours, as well as any backlogged cases we couldn’t get to earlier.

As Bing and I prepare to leave, the last thing I hear is Kalai on the phone with a caller. He’ll be heading out again for the night shift. Frankly, I’m not sure how he’s still standing; I’m so exhausted I want to nap right there on the floor of the car park.

“Hi, this is ACRES. Yes, can you please take a photo of it and WhatsApp it to this number so I can advise you…”

Stay tuned for Part 2 of this story.

Tell us about your wildest animal encounters at community@ricemedia.co. If you haven’t already, follow RICE on Instagram, Spotify, Facebook and Telegram.