Last week, the Foreign Interference (Countermeasures) Bill (FICA) was tabled in Parliament. A major follow-up to POFMA, it introduces dramatic measures aimed at countering foreign influence on domestic politics, including hostile information campaigns and disclosures required of ‘politically significant’ persons.

While FICA deserves robust scrutiny, given the extensive powers it gives the government and the large swathes of society it stands to affect, we found ourselves stuck on a first-order question: how can we discuss the Bill without understanding what foreign influence is to begin with?

Beyond vague concepts of bot armies, or high-profile instances like the 2016 US Presidential election, most of us have little concept of how foreign influence works in practice, and the extent of the threat it poses.

Ahead of the second reading of FICA, we spoke with Dr. Chong Ja-Ian, a Singaporean political scientist, to help us unpack what foreign influence is and Singapore’s attempts to address it. A recent Visiting Scholar at the Harvard-Yenching institute, his research involves security issues relating to China, Southeast Asia, Taiwan, and the United States.

The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect any institution or organisation. This transcript has been edited and condensed from a longer conversation.

Sophie: A broad question to start: what are we talking about when we talk about foreign influence? What does it set out to do, and is it always necessarily politically motivated or even hostile?

Ian: I think we can start by recognising that foreign influence is actually very broad. It happens all the time, and isn’t necessarily pernicious or something to worry about.

When firms invest in a country and say certain regulations need to be changed to facilitate that investment, that’s foreign influence. In Singapore, the National Wage Council, or the Singapore National Employers Federation have representatives of foreign firms there. When embassies or foreign Chambers of Commerce advocate for their interests, that’s all foreign influence. And Singapore does it abroad, too; if you look up the Foreign Agents Registration Act in the US, you’ll find the Singapore state and state-affiliated entities engaging in lobbying.

So we live with foreign influence all the time. But there is a difference between the everyday kind, which we don’t need to worry too much about if well-regulated, and the malicious kind, which seeks to undermine the political process or political system of a country, or otherwise damage the public interest in some way.

Without a stronger sense of common civic identity, disinformation campaigns can more easily target fissures in society, and have exactly the sorts of pernicious effects we’re so worried about.

Could you break this down a bit further?

When we look at the many things that constitute foreign influence, we should really only be concerned with a small subset, though of course this doesn’t mean it’s unimportant.

There’s a lot of talk about activity like Colour Revolutions or electoral influence, like in the 2016 US presidential elections, which are very dramatic but also easily observable. States that want to partake in this sort of activity have to bear a high level of risk and cost, which makes them rarer.

Often, the real intent of disinformation campaigns is to sow confusion and distrust. Sometimes these occur ahead of an actual military campaign to confuse the adversary. Sometimes, they’re meant to sow discord over a decision. One of the allegations is that in the 2018 local election in Taiwan and its referendum on same-sex marriage, disinformation campaigns from the PRC sought to sharpen social division by turning people against each other over LGBTQ issues.

What I find more worrisome are efforts to target individuals in key places in attempts to change policies, perhaps in ways damaging to society’s interests, or affect political processes in ways which might exclude fuller political participation.

To me, these deserve more attention because they tend to be harder to observe. By the time people realise it, the damage might already be done.

The idea of difference for people can be scary, especially when there are multiple anxieties at play … [i]n my view, we shouldn’t fixate on foreignness alone, but focus on behaviour. What kinds of behaviour are acceptable, and others less so?

What about cases where the instigator is a non-state actor?

These happen as well. You have commercial actors who are essentially hired guns, like Cambridge Analytica, who design campaigns for whoever pays them. The Reporter has written about content farms based in Malaysia—allegedly also involving people from Singapore—which targeted audiences in Taiwan. They might not always have much impact politically, but they are still efforts to manipulate opinion.

There are also cases where media outlets get swept up in this. They might want to cover something in another country, but lack the expertise or resources to send correspondents over, and end up buying content produced by some of these actors.

For example, during the 2019 protests in Hong Kong, some Malaysian papers which wanted to cover the protests ended up acquiring content from PRC media firms, which were trying to push a particular narrative.

Based on this, would it be fair to say that many of the people who end up facilitating such campaigns are more of unconscious agents, rather than deliberately acting on behalf of a principal?

There are malicious actors, but they are relatively easily spotted, like the 50 Cent Party from the PRC. What’s more complex is when people buy into a message without realising there’s something wrong, start pushing it out themselves, and convince others to do the same. This might be because they’re less informed about an issue or have existing anxieties, like with the anti-vax movement.

That’s how you get the amplification effect. The message looks a lot more organic, people re-interpret it through their own lens, and it becomes much harder to go after. Disinformation is most effective when people actually believe it.

So in this sense, a lot of these people are also victims. We might introduce laws targeting them and say they’re acting on behalf of a foreign principal, but they might not even be aware that they’re doing this.

This reminds me of a Reddit thread I was following last year, where a number of young Singaporeans expressed worries about their parents self-radicalising with pro-PRC propaganda. Insofar as better media literacy is part of tackling foreign influence, what are your thoughts on how this might work in practice?

Some degree of skepticism might be helpful—looking for corroboration, perhaps not taking things you see online for granted. But of course, not everyone is like this, and even then there are limits; people can be so skeptical that they end up getting into conspiracy theories.

You also have people who are more accustomed to being passive receptors of information, or have some existing belief in the messaging. It also plays on trust, because we believe information more easily when we hear it from people we know, or who have some expertise or authority. This is where you get your Russia Todays of the world, who try to create some aura of authenticity and expertise which people respond to.

Part of the solution involves being more critically-minded. It’s hard to encourage, but what’s just as challenging is to get people more engaged with issues, and accustomed to debate and differences in opinion. It’s not a silver bullet, but it’s a key part of media literacy.

There was some talk about this in the lead-up to POFMA in 2019, but by and large, better media literacy and things like independent fact-checking generally haven’t been particularly pushed here in Singapore. It does not seem to be an official priority while private or civil-society efforts seem lacking, perhaps because they’re under-resourced.

Recognising the larger points at stake can help us get over the worst effects of malign foreign influence. This goes beyond having laws that punish. It’s about active citizenry, transparency, accountability, restraint on authority.

Putting all this together, why is general public awareness of foreign influence operations so low? There are many high-profile examples, as you’ve mentioned, and even here, we’ve seen things like the Huang Jing case. But it strikes me that while we know foreign influence is a threat, we don’t really understand where the threat is coming from, what it can look like, and where we fit in all this.

To some extent, these activities are difficult to report on because the whole point is that there’s supposed to be plausible deniability. They’re designed to be harder to track.

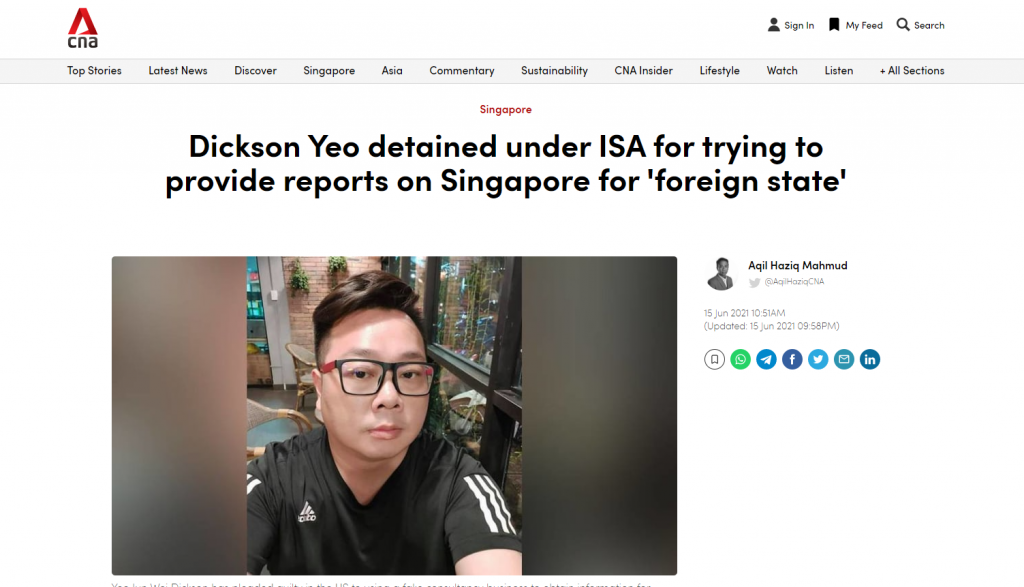

This said, in my view, the state in Singapore is very wary of opening up further discussions about what’s been going on. If you look at the Huang Jing case, who he was acting for was never fully disclosed by MHA. Or if you take an espionage case, that of Dickson Yeo— we know from public US Justice Department documents that he was spying on behalf of China, but MHA’s statements don’t mention the principal he was working for.

When cases do come up here, explanations often aren’t given for the decision not to release further details. When they are, it tends to be national security, which is okay, but that label doesn’t necessarily help people understand what the real dangers are or why exactly we need to be wary.

I suppose someone in a position of authority might say there’s a tradeoff involved, but it’s not entirely clear to me what the considerations there are or if they are the same across circumstances, especially if we’re being told that foreign influence is something to be worried about.

Generally, the more people know what to do and what to watch out for, the more protected our society will be. Relying on the national security label too easily deprives the public of the ability to protect itself.

Malicious actors are relatively easily spotted. What’s more complex is when people buy into a message without realising there’s something wrong, and start pushing it out themselves … [W]e might say that they’re acting on behalf of a foreign principal, but they might not even be aware they’re doing this.

While we’re on the topic of Singapore’s responses, could you sketch out how our approach to foreign influence operations has changed over the years?

Since even before independence, the colonial, the Malaysian, and the Singaporean versions of the Singapore state have all been very wary of malign foreign influence, be it the Communist threat or Indonesian infiltrators. As a result, we’ve had legislation like the Sedition Act, the Official Secrets Act, and the Internal Security Act, which give the state a lot of powerful tools to address foreign interference.

Over the last 10 years, with greater access to the Internet and information, there’s been rising worry about the general population being vulnerable to dis- or mis-information. This is where POFMA, and now FICA, come in.

So that’s one major area of Singapore’s approach. The other, which I think is important but has seen less movement, is efforts to get officials to disclose their interests and activities.

You alluded to this earlier on—efforts to target individuals in key places.

Yes. For starters, MPs must declare an interest in an issue before speaking on it in Parliament and cannot vote on matters where they have a direct pecuniary interest. According to the Rules of Prudence, PAP MPs must make disclosures to the Secretary-General of the party, ie. PM Lee himself. What we see in FICA is an effort to formalise these existing reporting mechanisms.

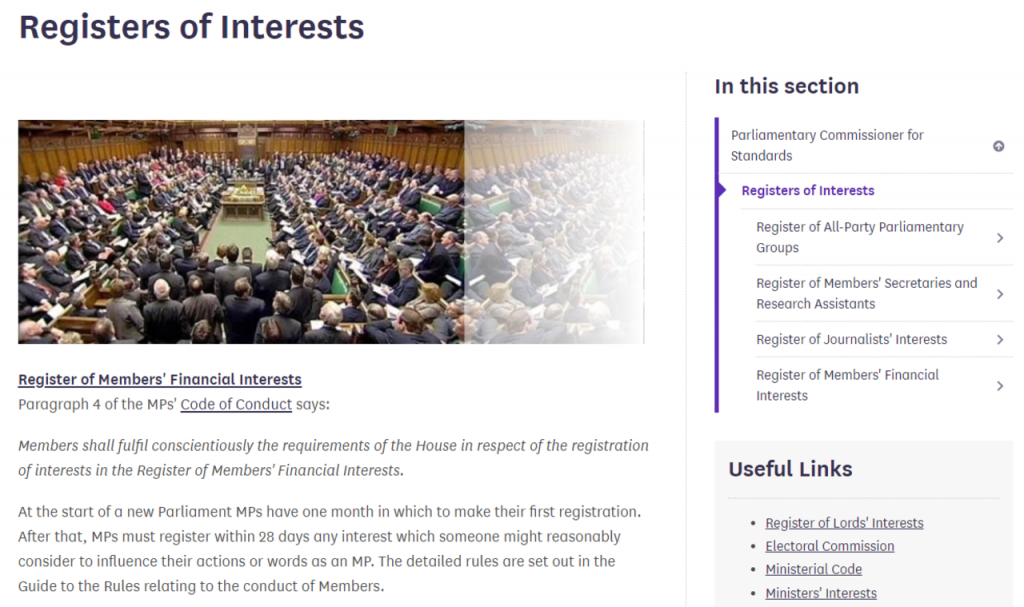

Where I think we haven’t gone yet is to move towards public disclosure — not just to the state, to the public — which can help prevent elite capture.

Public officials and elected appointees who are paid for by the public dime are supposed to work for the public interest. The UK and Australia have publicly searchable registers. Graft used to be a big problem in Taiwan, and instituting such a regime helped reduce this.

These steps haven’t been taken here, nor is there much regulation on lobbying. Earlier, I mentioned FARA in the US. The disclosures are all searchable by the public, including the contracts themselves and what they cover. It’s not perfect, but it’s a step forward. FICA does cover political donations, but I do think the level of public disclosure can be higher.

Similarly, we don’t really regulate the revolving door effect. In other places, when senior public servants or political appointees leave office, there may be a bar on their ability to lobby for a set amount of time. That’s not really done here, even though elected officials sometimes work for private firms after stepping down, and our MPs are also part-time and hold other positions, maybe even directorships.

Finally, I would say that there’s a public education element to this too. When I talk to people, including my students, they’re very surprised to hear that lobbying takes place in Singapore.

It’s not necessarily bad, it’s just part of the way constituents articulate interests to representatives. If you look at Section 120 of FICA, among the exemptions are lobbying activity by constituents. We shouldn’t pretend it doesn’t happen or say it shouldn’t happen, but we need a better understanding of what is permissible and what isn’t.

Generally, the more people know what to do and what to watch out for, the more protected our society will be protected. Relying on the national security label too easily deprives the public of the ability to protect itself.

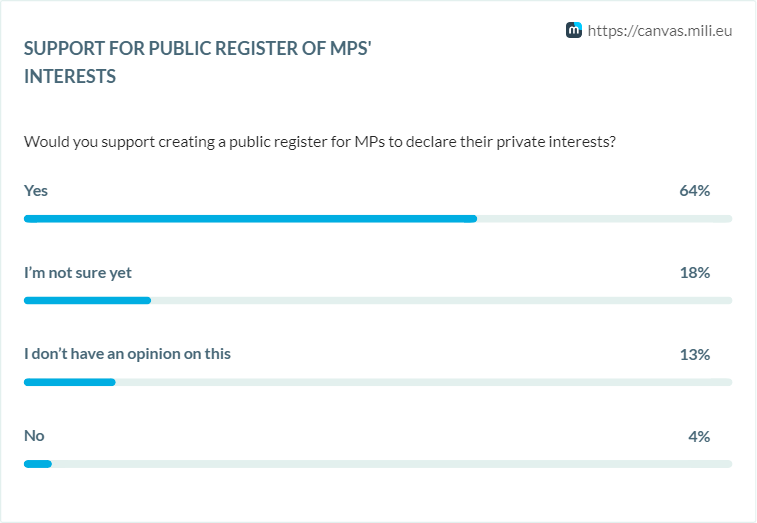

I’ve wondered about this too—last year, I wrote a piece arguing in favour of such a public register of MP’s interests. This said, a lot of these mechanisms rely on self-disclosure. Is that sufficient or does it need to be supported by auditing and enforcement measures?

Ideally it should be sufficient, but places with this kind of reporting also usually have an independent press. If an MP in the UK or their staff failed to declare an interest, because the press and civil society are always watching, they will dig stuff up. That’s the audit, in effect.

In Singapore, where we don’t really have an environment that is permissive for an independent press or investigative reporting, maybe what we need is not just self-declaration, but also auditing, which perhaps the Auditor-General could carry out. Self-reporting is necessary but insufficient, and we need to think about what other parts of this ecosystem have to be put in place.

Building on this idea of an ecosystem, we talked about media literacy earlier on, and you’ve mentioned various other things we should work on in tackling foreign influence: better regulatory and disclosure mechanisms, a free press. What else should we be doing?

In my opinion, what we don’t do much of here is to create a sense of shared civic values. In any polity, these give you a clearer sense of the terms of the debate—that even when people disagree, there is some common ground to frame the debate.

Recently, we’ve seen discussions about things like Chinese privilege and critical race theory. To me, some criticisms of these efforts suggest that there isn’t a strong enough sense of common civic-mindedness.

For instance, if Singapore is a multi-ethnic society, whatever your cultural affinities or self-identification may be, there needs to be a greater commitment to understanding the need for racial equality and the accommodation of difference.

Recognising the larger points at stake can help us get over the worst effects of malign foreign influence. This goes beyond having laws that punish. It’s about active citizenry, transparency, accountability, restraint on authority. Legislation is relatively easy to pass here, but it doesn’t address these deeper issues on which I think we need to do far more.

Without a stronger sense of common civic identity, disinformation campaigns can more easily target fissures in society, and have exactly the sorts of pernicious effects we’re so worried about. Malign foreign influence looks at a society’s fissures and seeks to exploit them. Beyond efforts like FICA, if we want to tackle it, I think that’s where we need to start.

I’m stuck on this, because while I recognise that we must start from somewhere—and perhaps things like nationality or sources of funding are the easiest pegs to hang things on—that in itself seems insufficient, when the concept of ‘foreignness’ itself is so porous, and it complicates who or what we should direct our energies towards.

I feel the focus we tend to have on foreignness is sometimes not completely helpful. If you say something is foreign, it can become a cudgel to beat someone over the head with. But if you ask who is foreign or what is foreign, you’ll get many different answers.

The idea of difference for people can be scary, especially when there are multiple anxieties at play. It’s also particularly difficult because we are an immigrant society facing significant pressures which cut across each other, like inequality, a need for cheap labour, and a need for technically skilled persons we don’t have enough of. All this creates confusion around foreignness, and perhaps a lot of fear.

In my view, we shouldn’t fixate on foreignness alone, but focus on behaviour. What kinds of behaviour are acceptable, and others less so?

You can have a foreign person who is completely law-abiding, and born-and-bred citizens who, for whatever reason, decide to do something against the public interest. Sometimes, in our eagerness to look for targets to vent our frustrations on, foreignness becomes an easy substitute for issues which really have to do with behaviour.

Efforts to target individuals in key places deserve more attention because they tend to be harder to observe. By the time people realise it, the damage might already be done.

What does being more discerning about behaviour entail? We’ve seen cases where foreign influence was alleged, but where there was no proof that this was actually the case. I’m thinking, for example, of the cancelled course at Yale-NUS in 2019, when Alfian Sa’at was accused of being ‘disloyal’, or the time PJ Thum and a few others met Dr. Mahathir.

We need a better grasp of risk or danger in order to address foreign influence and its risks more precisely—and, to some extent, calm ourselves down.

As with any other case, we should weigh the arguments for what they’re worth. Looking at the big hoo-ha over the PJ Thum-Dr. Mahathir meeting—I mean, I’m very certain PJ Thum is not going to be in any elected position any time soon, much less running the state! Just because people might listen to his opinions doesn’t mean they necessarily believe them.

Or take that incident some years ago where some Malaysian government vessels entered the waters off Tuas. People got riled up, some older gentlemen said they wanted to re-enlist to fight Malaysia… you get the drift. More recently, there was the exercise by the Malaysian armed forces which coincided with the rescheduled NDP, over which some politicians expressed concern.

It’s true that we ought to be careful and prudent, but this care and prudence should also mean a certain coolness of mind in addressing difficult situations. If we jump at everything we think is foreign and dangerous, that could lead us into tricky escalatory situations that can be difficult to control.

We do have differences with our neighbours, but neighbours sometimes have friction, and the key is in how we manage it, or handle it in such a way that it doesn’t escalate. This does not mean that we skip necessary preparations, just that we need to know what to do and when.