All images by Stephanie Lee unless otherwise stated.

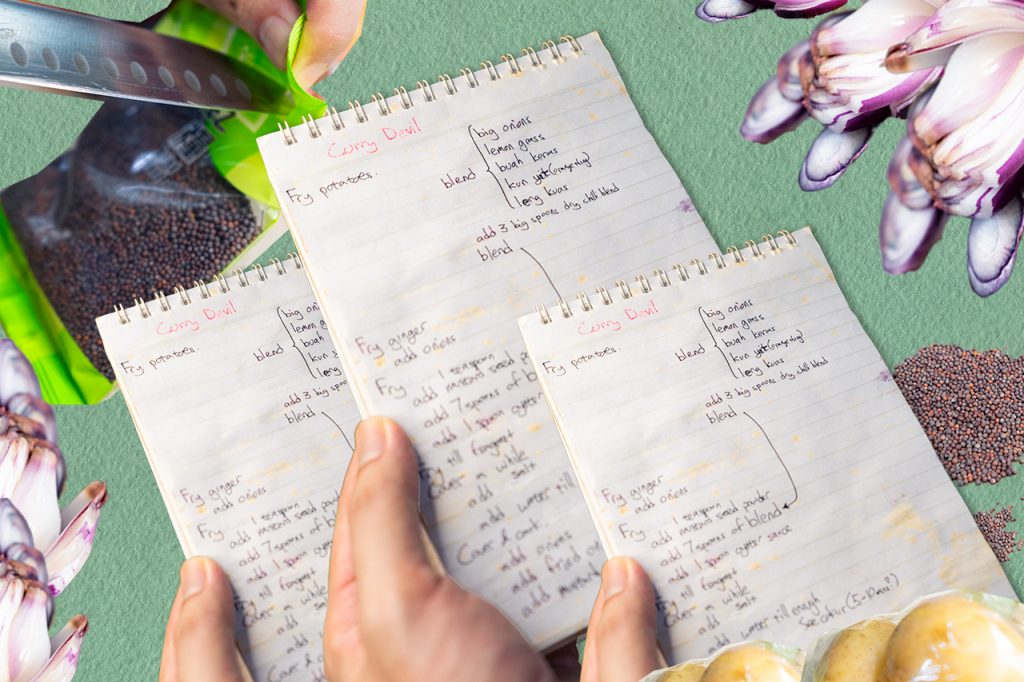

Among the Instagram Stories I’ve posted while sober, the one post I regret the most was my hand-written family recipe for devil’s curry.

To make matters worse, I also posted it on Facebook. This meant catching the attention of older Eurasian folks who fancy themselves as guardians of tradition whose opinions are never wrong.

The DMs arrived hard and fast.

“Why did you omit this ingredient? How can you add that ingredient?” To them, my family’s recipe is absolute heresy.

Whether you’re a home cook or a gutsy restaurateur, posting personal recipes online leaves you vulnerable to armchair critics who will enthusiastically go all Gordon Ramsay on your ass.

The criticism quintuples when it involves Eurasians and our beloved cure for Christmas hangovers: devil’s curry. Because it’s just as spicy to eat as it is to quarrel about among our people.

Eurasian Banter

Devil’s curry derives its name from ‘debal’, which is the Kristang (Portuguese Eurasian) word for ‘leftovers’. Curry, as you might be aware, is a word that has been used by many civilisations—as early as the ancient Greeks, to mean ‘sauce’ or ‘stew’.

The Kristang people descended from the Portuguese, who conquered Malacca and intermarried with local ethnic groups. As a recipe inherited from Portuguese colonialists and combined with Southeast Asian spices, devil’s curry, or kari debal, became a vital pillar of Eurasian culture. Devil’s curry is as central to the Eurasian identity as praying the Rosary, telling good jokes and mixing good cocktails.

The stereotype of the Portuguese Eurasian man is that of a lazy brown man (though skin tones, even among siblings, can range from Milo-brown to milky-white) descended from carefree fishermen.

We’re known to be charismatic, lack substance and are only good at these: Drinking, partying, playing music and telling stories. Alas, this is a sweeping generalisation. Eurasians like Dr Charles Paglar, Dr Benjamin Sheares and Joseph Schooling have contributed immensely to Singapore’s nation-building.

And, of course, we’ve contributed to the country’s culinary culture. Beyond its spices, meat and potatoes, devil’s curry has always been a spicy subject among Portuguese Eurasians, who like to criticise other families’ recipes and argue over what the authentic recipe of devil’s curry is.

As a part-Kristang child raised by my maternal Chinese family and educated in a Chinese school, I had very little inkling of what it meant to be Portuguese Eurasian. This made every Christmas in Singapore a unique and memorable experience because my family would visit our Kristang relatives, who are passionate about telling jokes, playing music and singing songs, not only in English but also in Bahasa Melayu and our Kristang creole, which is ancient Portuguese with Bahasa Melayu phonetics.

What kind of jokes? There’s my dad, who is adamant about getting an inappropriate joke in whenever he thinks of one. His trademark: Cracking fellatio quips when people are about to blow out birthday candles.

Banter among Eurasian men is a thing to behold or be annoyed with—we take turns throwing up jokes in a bid to make the group laugh and this leads to conversations becoming very disjointed. Eurasians usually don’t take to heart what’s said during these amateur comedy hours. Everyone will hardly recall what was said, but we always remember having a ball of time.

So you can imagine the spicy comments that get thrown around when we talk about kari debal every Christmas.

Kari Debal

Without exaggeration, Santa Claus takes a backseat to devil’s curry in the Eurasian Christmas experience.

Although the name ‘debal’ or ‘devil’ emphasises the fiery heat level (Sean-Evans-might-shed-a-tear level spicy), it also defines how this curry is made from leftovers, a distinguishing characteristic that is intertwined with its spiciness. If you happen to dabble a bit in the kitchen, you’ll know that some curries become hotter and more flavourful when kept overnight.

“Originally called Debal Curry, this most famous of Eurasian dishes was made on Boxing Day to use up all the leftover turkey, bacon bones, pork belly and roast chicken from the Christmas Day feast,” enlightens my second cousin, Cheryl Noronha, who just published a Eurasian cookbook back in October.

Called The Eurasian Table – Second Helpings, her book is based on the traditional recipes and memories of her grandmother, Theresa Noronha, a revered home chef in the local Eurasian community.

“Today, this dish has become the star of the Christmas Day meal. Traditionally, this recipe calls for a fresh, whole chicken,” divulges Cheryl.

I cannot overemphasise how good a chef Cheryl’s grandmother (my granddad’s sister) is. Not only did Cheryl and I eagerly count down the days to Christmas and her nan’s Christmas feast every year, but her grandmother’s culinary flair also attracted people from far and wide, who would queue up with us just to eat in her kitchen.

Acquaintances from the Balestier-Boon Keng neighbourhood and beyond would journey every Christmas to savour her to-die-for cooking, which made the queue to her kitchen stretch out of her living room and down the common corridor of her HDB apartment.

If I had to distil Portuguese Eurasian food to its fundamental tenets, this cuisine is rich but nuanced, which requires an experienced chef with a sharp palate to balance cooking durations and amounts of spices, in order to bring out the delicate, subtle, unmistakable and satisfying bottom notes of these dishes.

The flavour of devil’s curry, for example, is not supposed to be inundating and in your face, but nuanced with rarified sensations that don’t often grace the palate. Now, that’s something most Kristang chefs can agree on.

Who Gets to Define Tradition?

Currently, there are less than 20,000 Portuguese Eurasians in Singapore, and most descend from the conquerors of Malacca. And we can be quite argumentative about what constitutes our culture.

If you’re wondering, here’s my family’s devil’s curry recipe: Blend big onions, lemongrass, candlenuts, turmeric, galangal, dry chilli and ginger, then fry this blend with mustard seed powder, oyster sauce, salt, vinegar, meat and potatoes until you see it tumis, which is when the mixture undergoes a chemical reaction that changes its colour and flavour.

While Eurasians generally agree over these core ingredients, they like to argue over whether subjective ingredients like bacon bones, oyster sauce, and cocktail sausages are part of the ‘authentic’ devil’s curry recipe.

But here’s the thing: your leftovers are different from my leftovers. So who am I to say what goes into your curry of leftovers anyway?

Historical archives have proven that many ‘traditional recipes’ that we put on a pedestal today have not been passed down unaltered, but are dynamic culinary concepts that are still perennially evolving.

Chirashi don was invented only in the late 19th century, and salmon only became safe to consume as sashimi after the Europeans introduced fish farming to Japan in the 20th century.

Likewise, Thai food was not spicy until the Portuguese missionaries introduced the Thais to chilli. Moroccan mint tea is an idea that arose from the English offloading excess Chinese tea leaves in North Africa.

So I propose to you with confidence, that the first few renditions of devil’s curry in ancient times taste nothing like the devil’s curry recipes that we hold dear today. Ardent Eurasian traditionalists might find it difficult to stomach these facts, but Cheryl’s findings echo my sentiments.

“My research changed my perception of Eurasian cuisine. I’m intrigued by the dynamic nature of Eurasian food, appreciating how it continues to evolve over time,” she says.

“The dishes featured in the book serve as a testament to the evolving culinary landscape, not only across generations but also within the span of my grandmother’s lifetime.”

Cheryl and I do not know much about our great-grandfather and his wives, because most of them did not relay much of their life experiences and lineage to their children. Plus, they lived short lifespans.

“I love that the opaque past of most Eurasians means that they only know what a dish was like one or maybe two generations ago. So the way I create a dish is as authentic as how my grandmother did it, which is as authentic as how another family across Singapore makes it,” Cheryl affirms.

“I find that beautiful, and it removes the pretentiousness from the cooking, leaving just incredible food.”

Age-Old Arguments Over Authenticity

I asked local artist and illustrator Andre D’Rozario if he knew why Eurasians are so combative over their food.

“I think the hyper-focus on authenticity, at least in my experience, comes from not really having solid ground to root ourselves in because Eurasians in Singapore and Malaysia are part of a larger and global group of people whose identity is born of interracial mixing. The very thing that makes us special is shared by many others,” reckons Andre.

He would know—he published a graphic novel entitled Ki Sorti: Anoti Ngua (which translates from Kristang to ‘Hello: Night One’) in 2020 and also co-created the world’s first bilingual English-Kristang board game named Ila-Ila di Sul (‘The Southern Islands’).

While others like me might think that Eurasians fight over devil’s curry for shits and giggles, Andre opines that perhaps these combatants are simply trying to hold on to an identity that is loosely defined and relatively unknown.

“Sometimes, when your roots grow into something as shifty as sand, you end up all kinds of prickly. I think it’s hard to carve out an identity when your culture is drawn from your surroundings,” he offers.

“You’re everything and nothing, neither one nor the other, a partial imposter, especially when it comes to food. I think it’s hard not to feel your community’s identity is threatened when almost all aspects can be traced back to somewhere else.”

Andre opines that Eurasians shouldn’t agonise over the authenticity of their recipes or their heritage. Eurasians—or anyone searching for roots and identity—don’t have to dwell on finding similarities to reflect their community’s integration in a region. Rather than striving for conformity, shared idiosyncrasies add texture to a dish. Andre feels the authenticity of a dish lies in one’s own lived experience.

“Authenticity is subjective, and for me, it is about innovation, re-interpretation, and continuous movement, just as the Eurasians of the past moved forward,” Cheryl opines.

A Search for Roots

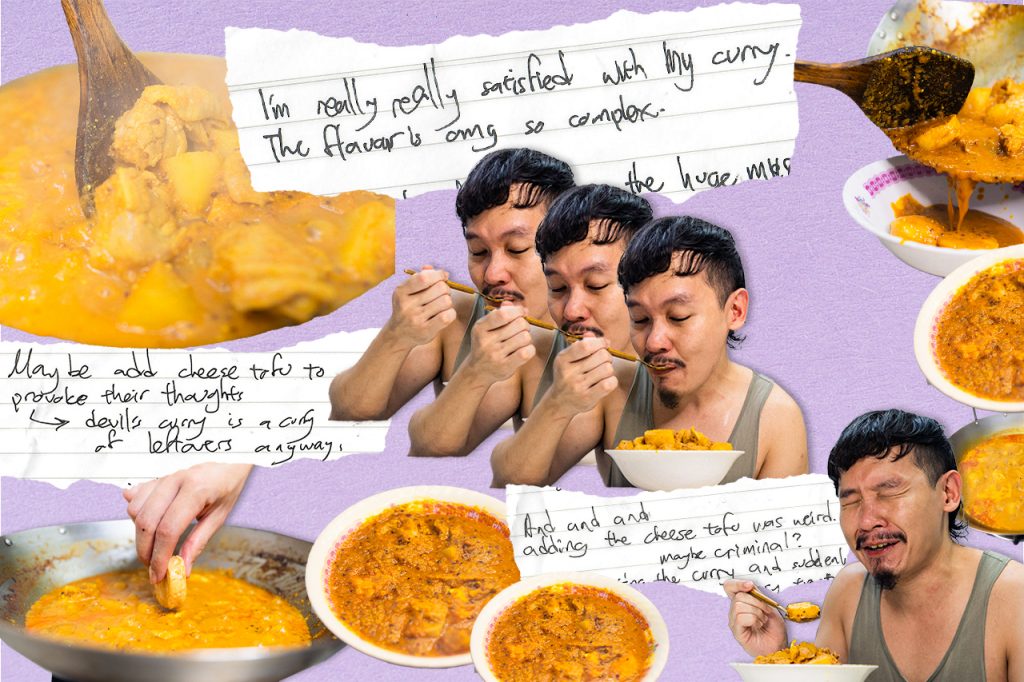

Emphasising the premise that devil’s curry is a curry of leftovers, I asked several Eurasians if plopping leftover cheese tofu into this curry would offend them.

Surprisingly, they all told me that if it tastes good, do it. Unorthodox as it is, cheese tofu is something that we all usually have as leftovers from the previous night’s Christmas hotpot. Who’s to say that it shouldn’t go into my curry?

As long as I live, there will be Eurasians who will argue over whose family’s devil’s curry is more authentic. Instead of zooming in on minute differences, perhaps we can focus on how Christmas is a culinary celebration of labour-of-love dishes that comprise great expertise and attention to detail.

At 91, Cheryl’s grandmother finds it difficult to stand up these days, so tasting her home-cooked dishes has become a rare treat. So I cling on with deep gratitude to the precious memories of her laborious Christmas meals.

Devil’s curry is not at all representative of Portuguese cooking styles. But it is historically reflective of the spice trade that drew the Portuguese to Southeast Asia and the culinary fusions of intermarried ethnic groups.

You can also view devil’s curry as a culinary microcosm of Eurasian culture; a combination of the best parts of everything and left to stew for richer character over decades.

Although I identify as Kristang, I don’t say this in public often because few people have heard of this ethnicity and understand its provenance. Even though most Singaporeans can grasp what a Eurasian is, Singapore currently states that any person of mixed European and Asian parentage can racially identify as ‘Eurasian’, which further exacerbates Andre’s aforementioned “identity shifting like sand” predicament of the Eurasian race and the Kristang people.

With that said, ethnic heritage comprises shared, fundamental traditions. Portuguese Eurasians are scions of recent-century interracial marriages and have not had a long runway to carve an identity by cementing such shared traditions (like devil’s curry). However, our young race has already been grouped as a drop in the vast ocean that is the ‘Others’ category.

So, if you meet a belligerent Eurasian who insists on defining a hard-and-fast devil’s curry recipe, understand that it comes from our valid desire to establish our roots.