All Images by Stephanie Lee unless otherwise stated.

“It appears that young couples live life and make decisions thinking they are immortal and hope nothing bad happens,” says an impassioned Shaik Amar, 30, a real estate agent better known as @thatproperty.guy on TikTok. “I understand people who want to stay in these Prime Location Housing (PLH) areas. But, as a young couple, buying yourself more options is much more important,” he stresses.

In just the last couple of months, the Singaporean housing market has been nothing short of a shark tank. There’s the BTO balloting system that left many Singaporeans disheartened, the much-maligned SERS project compensation saga, and the heated debates between MPs Mr Pritam Singh and Ms Indranee Singh about HDB pricing in parliament.

In response to all this heat, HDB and MND, in a historic move, made the decision to release the breakdown of the cost of BTO flats.

This story delves into yet another sticky tentacle of public housing in Singapore: HDB’s Prime Location Public Housing (PLH) model.

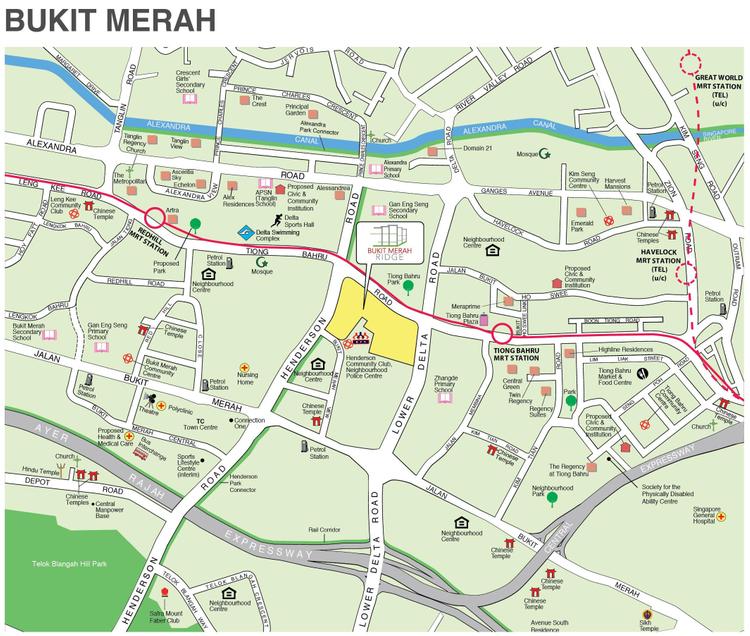

A subset of Build-To-Order (BTO) flats, the PLH model is the shinier, more coveted version of government real estate. These homes are located in mature and lauded areas like Kallang, Whampoa, Queenstown, and Bukit Merah.

As purported on HDB’s website, the PLH model is an effort to make “central locations affordable, accessible, and inclusive for Singaporeans”.

With PLH, everything from MRTs, hawker centres, expressways, and schools are only a hop, skip and jump away—what’s not to love and clamour? Still, like many things in life, especially in real estate, if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is.

Just like the slew of amenities you get with a PLH unit, there are a few caveats with PLH units that might give potential buyers a smidge of a pause.

Location, Location, Location

Those three little words make all the difference when hunting for property in Singapore. After all, a mansion in the far reaches of Singapore (think Pasir Ris) can’t beat a 4-room unit within minutes of the CBD.

“It’s mainly the location because, in terms of size between PLH units and other BTO projects, it is inconsequential,” says Xinyun, 26, who works in R&D and recently acquired a unit in the PLH project Bukit Merah Edge.

For both her and her husband, Suresh, 26, the unit at Bukit Merah Ridge fits their criteria since it was close to their parent’s home and workplaces.

“We like the location, and, besides the ease of access to the MRT, the area felt like somewhere we could potentially start a family in the future.”

More than that, they got a unit above 25 storeys, another important requirement Xinyun had for her future home.

For another successful pair of PLH buyers, Han Toh, 29, and his partner, the location of Bukit Merah Ridge in the trendy Tiong Bahru Estate, was what sealed the deal.

“I think the location is crucial to us; that’s the number one factor. Plus, my partner loves the Tiong Bahru area. She dreams of living in those black and white houses, but those go for S$1.5 million and only have 30 years left on the lease.”

Han and his partner have tried seven times to apply for a BTO flat, so getting this unit at Bukit Merah Ridge was a stroke of luck. As a proverbial cherry on top, Han and his partner managed to get a unit on the 46th floor, which is one of the highest floors of this project.

“We went to the neighbouring block of flats called City Vue@Henderson and went up to the 45th floor and saw the view. I was like, man; you cannot get this anywhere else,” gushes Han.

“We got the south-facing unit, right, so you can see Sentosa, a little bit of Bintan or Batam, Henderson hills, and a view of those black and white houses of Tiong Bahru. Plus, there’s no noise because you’re so high up.”

“Everything is accessible; there is Tiong Bahru market and Tiong Bahru Plaza, which has your bank, supermarket, and wet market. On top of that, it is also a stone’s throw away from Orchard. Everything is just perfect.”

It sounds like Suresh, Xinyun, and Han hit the real estate trifecta of location, view, and amenities, much to the envy of many prospective buyers. Still, real estate agents and publications are not so quick to laud this seemingly great housing equaliser.

Primed for Everyone

Introduced in October 2021, the PLH model was an affordable and accessible way to allow Singaporeans to live in central areas.

There have been eight PLH projects, starting with the oversubscribed River Peaks I & II with an oversubscription rate of 8.2. Other projects like King George’s Heights in Kallang-Whampoa saw oversubscription rates of 13.

Along with the prime location, PLH units are also afforded more subsidies, such that the price of the PLH unit is cheaper than a resale unit in the same area.

For example, a quick glance at figures for the PLH project Kallang Horizon sees a 4-room flat sold at a starting price of S$509,000. We can compare this to previous BTO projects in the area for the same-sized flats that range from S$488,000 to S$675,000. It’s a vastly lower price than the median resale flats in the area, which comes up to S$778,400.

If we were to make comparisons for the Bukit Merah Ridge projects, PLH units for a four-room flat go from S$540,000, while previous BTO projects in the area range from S$602,000 to S$710,000. The median resale flat price as listed on PropertyGuru comes up to S$750,000.

Some math will tell us that a PLH unit at Bukit Merah Ridge is about 28% cheaper than a resale flat in the area compared to the Kallang PLH projects, which is 34% cheaper than a resale.

So far, there is no reason or rationale for how HDB calculates this subsidy.

On top of that, buyers are afforded grants such as the Enhanced CPF Housing Grant, with a maximum payout of S$80,000, depending on their average monthly income.

Of course, one huge catch with PLH projects is the 10-year MOP period, which means that you would have to live in your unit for a minimum of 10 years before you can sell your HDB unit. This is double the time period for normal BTO flats.

There are also stricter renting rules. For regular HDB units, you can rent out the entire unit after five years. But PLH flat owners are not allowed to rent out the whole unit—they’re only allowed to rent out the spare bedrooms.

Additionally. seeing as PLH units are subsidised, if and when PLH homeowners sell their homes, there will be a subsidy clawback from HDB that homeowners will have to commensurate. This subsidy, according to HDB, varies from project to project and is not fixed to income levels.

To date, the exact percentage of the clawback amount has only been announced and confirmed for pilot PLH projects, River Peaks I and II, fixed at six per cent of the higher resale price or valuation. As for the other seven projects, more details have yet to be released.

A Mountain Out of MOP

The biggest elephant in the room when speaking about the PLH projects has to be the ten-year MOP. Not to mention, there is a five to six-year wait for the project to be completed.

Bukit Merah Ridge, for instance, will only be completed in late 2027 or early 2028. Surprisingly, this was the least of concerns to both Suresh and Xinyun.

“MOP was not an issue because when we made our purchase, we didn’t see our unit as an investment,” says Suresh. “We saw it as somewhere we are going to stay until maybe our hair turns white or until I’m bald, you know?”

“I think I never considered much about the MOP for the place,” Han chimes in. “We were just looking for a place where we hope to stay for the longest period of our lives. Since it met our criteria, it meant there was a less likely chance for us to move out after the MOP. The fact it has increased from five to 10 years doesn’t impact our decision.”

While the new homeowners I spoke to seem relatively unaffected by these new MOP rules, as a real estate agent, Shaik is much more uncomfortable with this significant change.

“We are looking at a 10-year holding period, which is a very long time to lock yourself and your funds into an asset,” asserts Shaik. “It is effectively two real estate cycles if you think about it.

He goes on to explain that while a young 25-year-old couple earning a combined income of about S$7,000 can afford a PLH now, he stresses that their life would look completely different by the time they are 35 years old.

“One small thing can upend the best-laid plans,” Shaik reminds me. “Even for the five-year MOP, that’s still a significant amount of time to be unable to sell. It’s really scary.”

“The problem for me is that you have so much growth in just five years, and to think that you would remain stagnant for the next 15 years, is a little naive,” Shaik explains. “I feel that you are locking yourself in for a future where you would have no idea how it would turn out or the kind of person you are going to be.”

The capriciousness of the real estate market is something Shaik knows all too well. Even as homeowners emerge from the 10-year MOP, there is no guarantee there will be demand for PLH units, as a fresh 10-year MOP and rental restrictions would be passed on to resale owners.

We also have to consider the eligibility criteria for the family nuclei of PLH units. Families that apply must be Singaporean citizens or Singaporean Permanent residents.

“As such, the overall pool of buyers that would be willing to put themselves in the resale position for a PLH unit 10 years from now, assuming there will be buyers, is very low,” add Shaik. “That makes it very hard for you to exit the property.”

Of course, Shaik stresses there will always be people who can afford to take that risk, but he fears it might lead to a possible domino effect in the real estate market.

According to Shaik, the prices of HDB flats that are not considered PLH projects but are in PLH areas will skyrocket in future. He cites projects such as Sky Oasis@ Dawson along Margaret Drive, a BTO project in Queenstown, which doesn’t have the same MOP and rental restrictions as other Queenstown PLH projects such as Ulu Pandan Banks and Ghim Moh Natura.

“Look, it’s not wrong to buy a forever home. Sure, buy a forever home, but have plans and options to exit. Having an exit strategy in place, especially with housing, is very important,” he stresses.

Renting Is Not Just Passive Income

PLH, with all its new restrictions, is quite clearly an effort by HDB to curb rent-seeking behaviour and discourage buying homes as investments.

Not everyone, like interviewees I’ve spoken to, buys an HDB unit with the intent to flip to make a profit; rental restrictions don’t even cross most people’s minds, if at all. Most buyers like Suresh, Xinyun, and Han are in it for the long haul. For them, renting just seems like a greedy money grab.

“If you want to live in a house, you shouldn’t see it as somewhere you are only going to stay for five years. Why impose a limit of just five years rather than 50 or 60 years?” asks Han. “So a 10-year MOP shouldn’t affect your decision. If you can’t see yourself living in your BTO for ten years, maybe you shouldn’t have got it.”

“For all intents and purposes, every time we were looking into a house, we never thought about it as an investment,” adds Suresh. “When we look at a house, we focus on how many years it has left or whether it even meets our conditions.”

Plus, Suresh and Xinyun stress that given the renting restrictions, they are uncomfortable sharing family or private space with strangers. “No matter the conditions set, we probably will not rent out,” says Suresh. “We want to build a home, a family and have a house where we can spend the rest of our days.”

Even though Shaik agrees that renting has a bad rap, he also sees it as a lifeline for some who desperately need the money.

“Because I’m on the ground, I often see people who cannot pay their mortgage move back with their parents,” says Shaik. “Renting for them is a way to sustain those tough months.”

“You have people who have fallen ill and need to move back with their family and use their rental income to pay bills. There are also some older people who want to live with their kids.”

Shaik has even encountered people working abroad for a year or two who rent out their units to cover their mortgages. “Sure, you might never want to rent your property, but you just want the option in the event you have to.”

The Folly of Youth vs a Looming Housing Crisis

Attaining a queue number is akin to winning the lottery—what more is a house that fits all your needs. You too, I’m certain, would say yes in a heartbeat and start scouring Pinterest boards. Xinyun and Suresh are already thinking about how they are going to fit in a Harry Potter-themed room.

As much as playing house is fun, Shaik believes that this rush for housing without thinking about the long-term effect is truly the folly of youth.

“It is the inability to delay gratification and to look at where you are going to be versus where you’re now,” says Shaik.

He agrees and understands a strong need for home ownership that’s precipitated by Circuit Breaker and Covid-19. “Still, people must understand that this is the only compulsory investment every young Singaporean has to make, so don’t lock yourself into a decision you cannot get out of.”

Rather than trying so hard to get a house, financial literacy is the most important thing we can focus on.

“I hope the current generation will know how to handle their money and property better because only then will we see a much better, more stable property market with lesser people letting go of their properties because they can’t afford it anymore.”

We Can’t Let Go

Even as Suresh, Xinyun, and Han are cognizant of the drawbacks of PLH housing, getting a house in this climate is such an achievement that letting it go seems like a waste.

When Suresh proposed to Xinyun in 2020, they immediately made plans to secure a house. “Even if the MOP rules pose a risk, I think that the flat’s location is too good to let up,” says Suresh.

“Of course, I wouldn’t say ‘never’ to moving out because of the appreciation of the PLH unit, given the location. But it will not factor into whether we get another house unless we are strapped for money. It’s improbable for us to go through a financial crisis because I think we are sufficiently prepared with our finances,” Suresh tells me, confident.

“It’s a risk that I hope will never happen. I hope that there will be no emergency in which we both would require to live with our families or even be in a situation where they need to live with us.”

On top of not giving up a good flat, there is also a rush and peer pressure to secure a house as soon as possible. Suresh and Xinyun are only 26, but they consider themselves geriatric buyers compared to other buyers in their chat group.

“I think we are purchasing our flat a little late. When I was in the chat group, there were mentions of some people who were still studying. I was quite shocked.”

The same fear of losing something great is also evident in Han and his partner. “If we give this up, who knows when the next opportunity will come?” says Han. “On the record, it is stated that you turned down this HDB unit, so your chances of getting the next one are lower.”

“Everything worked out for us, and it’s the unit we’ve always dreamed of. Our unit is next to the black and white houses and is so convenient; the location is just too good to let go.”