Education has never been a one-size-fits-all affair. It’s common wisdom, but bears repeating: children learn differently, and have various interests, some of which exist outside the boundaries of school. There may be children with an innate curiosity for the language of mathematics, and respond well to verbal instructions; equally, others may be hands-on learners who enjoy discovering architectural principles by taping straws to build a bridge across their Lego buildings.

Accordingly, for decades, Singapore—and countries everywhere—have been trying to expand the parameters of their education system to accommodate a variety of passions and learning styles. For instance, the Ministry of Education (MOE) has recently introduced “makerspaces” in schools that let students tinker with engineering tools and create things.

Yet the end goal of our education is, arguably, still the same: (ideally) excelling at a standardised test to fulfil a national admission criteria, all of which do not take into account different paradigms of learning and doing, and, more broadly, of living in the world.

And despite the unusual circumstances in which it arrived, HBL has proven to be the same formula dressed in fancier clothes.

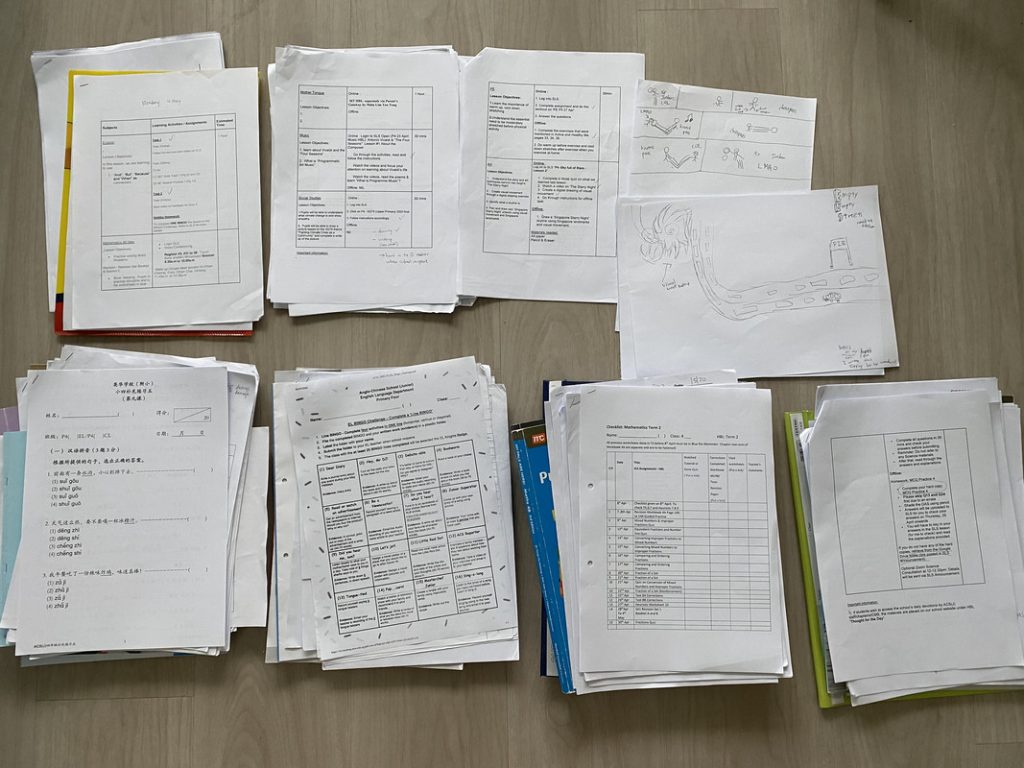

There are assignments not only for English, Mother Tongue, Math & Science, but also for Art, PE and Music.

Similarly, Michelle Choy, an occupational therapist, writes on her blog: “[My son] shows me his SLS portal. So many items under the ‘in progress’ column! With 8 subjects and various tasks tied to each, and some from the days before, it was a complete mess.”

Admittedly, it’s not “a complete mess” for all, but it’s been a challenge for many, students and parents alike. Students might not take to learning about algebra from an impersonal video, like Michelle’s son (“you couple ‘not knowing how to do it’ with ‘I don’t want to do it’ … and the child is just stuck,” Michelle laments to me). And parents now have to juggle their own work, their parenting, and their psychological health, with being a teacher.

“MOE states that parents are not expected to teach,” Michelle clarifies. “But the reality is that not all students can pick up these subjects via remote learning.”

Zac’s Mum agrees: “HBL was like having a trainee colleague suddenly forced under your wing. Besides your regular workload, you now have a green newbie who needs to be trained in how to use and navigate the unfamiliar I.T. system … You have to … brief him daily. And then check in on him to find out if he’s managing ok or simply slacking while you’re busy coping with your own work!”

For Michelle, her Primary 2 daughter enjoyed HBL, but her son struggled with HBL. He had so many incomplete assignments that his teachers inundated her with daily text messages. Eventually, Michelle sent an email to his school to explain that he was not coping, and both she and her son would take responsibility for any of his uncompleted assignments.

“HBL is not for everyone,” Michelle plainly states.

If they can’t?

“There’s no point [going on with HBL then]. They can do other things in the afternoons,” Michelle concedes.

“This is an experience that we’ll never have again, when the family is home the entire day. It’s a good opportunity to bond, to play games together. My kids are doing a lot of baking, cooking, and crafts. One had time to work on her painting hobby and has received orders for her portraits. Another is launching her own jewellery business … my 7-year-old was inspired by them … and started selling $1 bookmarks. And she’s donating the money to charity.”

“These are entrepreneurial skills. Empathy. Gratitude. I guide them to find their passions and purpose, and to look beyond themselves … They are learning about the world around them.”

What about her son?

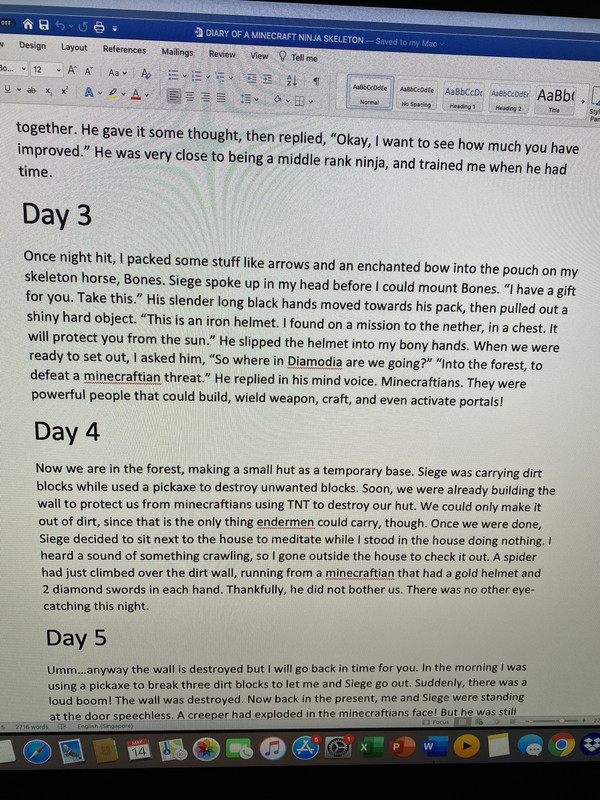

“That one … it’s a bit more challenging,” Michelle laughs. “It’s hard to get him off his games. I don’t have that issue with my five girls. … So, for the first time I sat and watched him play Minecraft. As an occupational therapist, any time I observe my children participating in activities, I’m assessing what skills they are learning.”

To her surprise, she realised that he was potentially learning more from his game than from his miserable experience with HBL.

“He says, ‘Mum, this is mimicking real life. This is a farm. We have animals, we learn how to cook them for food, we build our village.’ He tells me where to put windows, how to allocate his resources to maximise this or that. And he can explain his rationale for doing so. That is important.”

“There are so many skills involved. Problem solving, collaboration, creativity, design, and architecture.”

In addition, Michelle’s son is also teaching his 7-year-old sister how to play Minecraft, which has impressed Michelle.

“Being a teacher is difficult. You have to break down concepts into easily understood ways. You have to learn to be patient, and you have to enter a shared world together. You learn that it benefits you if you share resources and help each other out. ”

“I look at the skills he’s been acquiring by playing Minecraft, and I think, I’ll leave him to it.”

I was … unhappy about being told how to educate my child in my own home … I believe parents should have a choice or say in how they want to parent their children at home during the circuit breaker, since we are the ones most familiar with our circumstances (how many children and what ages), or space configurations (sufficient workstations or not?), number of devices available, availability of parent to help, etc.

Taken in totality, the design of HBL—its adherence to the standard curriculum in school, its insistence on one form of pedagogy, its assumption that families are homogenous in their ability to carry out HBL—is founded upon the desire, or some might say, delusion, that it is business as usual. Schooling and education, with its standardised teaching and testing, must go on. Consistency is the order of the day.

This approach seems to be designed to show that the nation can get its act together even when systems are disrupted and society is fragmented. That standardised education is still a priority and that children will not be left behind.

To be sure, neither of the mums I spoke to desired a radical overhauling of Singapore’s education system. Zac’s Mum states: “I’m not unhappy about education in SG, nor do I have any suggestions for schools and MOE.” And while Michelle “admires Finland’s education system” (which has moved from examining discrete subjects to “phenomenon-based learning”), she does not think the Singapore education system is “behind”. It’s just that “Finland is ahead”.

At the same time, it’s hard not to conceive this as a missed opportunity at re-evaluating the purpose of our children’s education and why schools exist. As the anecdote about Michelle’s son playing Minecraft illustrates, there are forms of child-directed learning (often termed “unschooling“) that do not involve the stress-inducing, competitive atmosphere fostered in schools.

I look at the skills he’s been acquiring by playing Minecraft, and I think, I’ll leave him to it.

“When we go back to school everything will be different – and it must be different,” Niamh Sweeney, a teacher, writes. “We cannot continue with a toxic exam system that is based on rote learning and an out-of-date curriculum … and an exam system that has been responsible for a dramatic rise in child and adolescent mental health illness.”

“We must end the fixation with A-levels as the ‘gold standard’, just because they’ve been around a long time. Our education system must recognise the achievements of all and must not continue to label those who take a vocational education route as less worthy or less valuable, or their qualifications less rigorous.”

After all, healthcare professionals aside, we don’t see degree holders deemed as essential workers or heroes during this time. It’s the people who are fixing our burst pipes, the locksmiths who save us from being homeless when we stupidly lock ourselves out of our houses, the hawkers feeding us, the bus drivers who keep Singapore moving. The pandemic reminds us that these vocational skills have for so long been undervalued, but none of us can do without them.

It’s also revealed to us that so many families, mine included, have forgotten how to coexist in a space for an extended period of time. We’ve forgotten how to communicate, how to manage our emotions, how to offer solace to one another. This is about cultivating emotional intelligence—something the current HBL curriculum doesn’t address even in passing.

As Helena Gillespie, a professor of learning tells the BBC, “Children won’t remember finishing that geography homework, but they will remember how it made them feel and what the vibe in the house was like.”

And if we insist on pretending that it is business as usual, then we are missing out on the opportunity to ask ourselves what we want our children to remember when they come out of the school year. Will it just be that they went to school “virtually” when there was a pandemic raging around them, and spent a lot of time feeling as frustrated as they did while in school? Or will it be that they picked up new things organically while pursuing their hobbies—with no one activity deemed more or less valuable— and learnt how to weather a storm with their family?