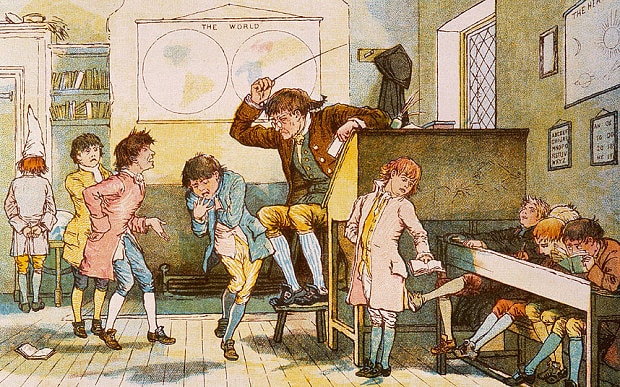

There are two types of stories on the subject of caning children.

Type A is what I call the ‘civilisation’ piece. Usually written and published by a Western liberal, the ‘civilisation’ camp condemns corporal punishment of any kind as barbarous, backwards and borderline human rights abuse.

The postmodern parent, it argues, should not use violence because that’s what African warlords use and spanking your child is no different from ‘torture’. It is only separated by degree.

Closer to home, we have Type B, a.k.a the ‘pragmatic punisher’. Written by a Singaporean of conservative bent, this camp never discusses the right and wrong of caning at all. Corporal punishment is a constitutional right, and the only questions we should ask are how hard, how often, and what type of cane.

Morality is irrelevant as long as the punishment is effective. This is the way it has always been and always should be, unless you want your child to grow into one of the rebellious young punks from Trainspotting.

Both types of arguments are incredibly annoying. Type A is not about parenting or children at all. It is a kind of high-level virtue-signalling where you prove your adherence to the flawed morality of Western liberalism.

While there are good arguments against caning, ‘civilisation’ is not one of them.

Type B is equally bad for different reasons. It argues in favour of caning because it is traditional and is ‘proven to work’ as a form of discipline. The problem with this is a total lack of evidence except anecdotes, and anecdotes cannot provide any meaningful conclusion to the issue.

For every child that turned out well thanks to caning, you can find another child who turned out equally well despite a lack of caning. Every school might be a good school, but every child is different; you can’t argue for its efficacy just because it seemed to work for your son. Who can say that it was caning and not good parenting that made him an upstanding Singaporean citizen? What if she had turned out even better had you spared the rod?

In any case, both of these perspectives miss the point. They are so obsessed with efficacy/abstract morality that they forget to answer the most basic question about caning: Is this the kind of pain that should be inflicted upon a child?

To answer the question, I got caned for the first time at the ripe young age of 26.

Allow me to explain.

In childhood, I was beaten and scolded but never caned. My parents were generous with their slaps but they refused to cane me because instruments of pain somehow crossed an invisible line. As a result, I’m a rotan virgin who has never experienced the pain that so many of my friends recollect with bitter fondness, possessing no real opinion on caning except ‘phew, lucky not me’.

Now that I’m a person in his mid-twenties, saddled by mortgage and career, this question seems more urgent than before. If I do have a child in the near future and make Josephine Teo proud, shall I continue to abstain as my parents have done or apply the rotan with judicious zeal as so many folks recommend?

This is not a question that I can answer—or anyone should answer—without the first hand experience of wood meeting flesh.

So in the interest of knowledge and content, I bought a thick rotan from the mamashop behind my house and handed it to my editor, who was more than eager to exact revenge for missed deadlines and lacklustre writing.

After changing into shorts and painting a target on my hand, legs and buttocks, I was ready for a thrashing. After all, I survived NS to box a little in uni, and my editor has the musculature of an anorexic weasel. How painful could this be?

Pretty fucking painful, as it turns out.

The first hit fell like a wet noodle upon my palm because Mr. Associate Editor felt odd caning his colleague. But his second, warmed-up blow stung like hell. I couldn’t help flinching and drawing my hand back instinctively.

On a scale of one to ten, with one being a warm breeze and ten being the most painful thing I’ve ever experienced (getting kicked in the ribs by a heavyweight boxer), this is a solid 4. It is definitely sharper and more memorable than my mom’s bare hand, even when she was on form.

After the sting wore off, the flesh on my palm remained warm. Soon, a visible red line would appear and remain for the rest of the day. A tangible souvenir of punitive justice that looked like this:

Before I could use maiming as an excuse to shirk off work, we moved on to the butt and I found myself bent against a table, reevaluating my life decisions as adult.

Since this is how our justice system canes rapists and drug traffickers, I thought this would be the most painful posture, but it wasn’t. The two strokes that landed on my glutes did hurt, but they were nowhere as painful as I expected and a far cry from the hand-caning I received 5 minutes prior.

The impact produced a satisfying thwack sound, but left no visible mark (I checked) or lasting pain, probably because you have abundant flesh on your posterior to cushion (and dissipate) the force of the stroke. In other words, fat ass = less pain.

Yet despite being less physically painful, I would much prefer to be caned on the limbs. Pain is easier to deal with if you can anticipate it; that’s why doctors always tell you ‘this is going to hurt’ before they stick the needle into your arm. Buttock-caning prevents you from seeing the instrument of suffering and leaves you unable to brace for impact.

The nervous anticipation of when-is-it-going-to-come ends up being more painful than the actual sensation of getting hit. And there is also the added humiliation of getting hit on a part of your body that is normally taboo to touch.

Finally, I was caned on the arms and legs, but all that felt like a mild afternoon breeze after the visceral experience of butt and hand.

8 strokes and some thinking later, I’ve decided against caning as a form of punishment for any potential offspring. Here’s why.

Unless he or she does something truly terrible like theft, punching a classmate, or failing to apologise to Grace Fu, I would advocate for non-violent punishments in place of corporal discipline.

Having now experienced it firsthand, I do not think that caning is reasonable amount of pain to inflict upon a child for minor offences like failing math or being ‘lazy’. If my emaciated editor could leave a mark and make a jaded leathery bastard ‘feel’ something, I cannot imagine how this would feel for a young child, tender of flesh and heart.

The pain he feels would probably be a 7 or 8 since it is not softened by experience, cynicism, or an ability to see the humour in his situation.

And I didn’t even get to experience the helplessness or the emotional turmoil that caned children undergo.

Of course, some people would argue that this is whole point of caning.

Pain is good. Pain educates. Pain reforms and deters.

But these so-called cardinal truths are no more than unsubstantiated conjecture. We often point to ‘rebellious youth culture’ in America or Europe as negative examples of what happens if you do not cane your children, but we forget to look at countries closer to home that do use corporal punishment to little effect.

According to a study by the Brookings institute, our main compatriots in caning are Nigeria, where 91% of children are violently beaten, and Egypt, where the violent discipline figure is 81%. Judicial corporal punishment is practised in the state of Indonesia, Pakistan and Somalia, all of which have abysmal public safety records.

Given these numbers, I find it hard to argue that corporal punishment leads to good behaviour. If Singapore is safe, it is probably not due to caning alone, or I would be planning my 2-week vacation in Somalia.

So given the not-insubstantial pain it causes and the lack of good evidence that it works, I don’t think caning should be used as your de facto disciplinary device.

Honestly, just smack your child instead. Unless your cane is made from a piece of the true cross, it probably doesn’t make much of a difference in getting the message across.