Not because I was rebelling against the system at the age of eight, but because I didn’t see the point in buying an outfit I would only wear for one day out of the entire year.

Back then, no one really cared about Racial Harmony Day. Coming from a SAP school, there was only one non-Chinese student in my entire cohort. Racial Harmony Day was more of an excuse to wear whatever Chinese New Year clothes you’d bought than anything else.

Fifteen years on, I’d like to think I have a more nuanced and in-depth understanding of race and related issues in Singapore. What I don’t know is how much of this is because of Racial Harmony Day.

These days, Racial Harmony Day is mostly observed in schools—it was launched as part of the Ministry of Education’s National Education programme—although grassroots organisations, like the People’s Association and Community Development Councils, also actively celebrate it.

In theory, there’s nothing inherently wrong with appreciating each other’s cultures, costumes, and food as long as these cultural exchanges are conducted respectfully.

But we can do more than this to lend meaning to the day.

First, Racial Harmony Day can often be superficial. Children get a brief glimpse into each other’s cultures, but aren’t taught how to dig deeper, to learn about the deeper meaning behind the fabric or the motifs of the clothes we wear, the symbolism in the colours of our traditional dress, or the stories that lie behind a simple item of clothing or accessory.

At best, we wear the clothes for the day, and forget about it until the next time we have to wear a baju kurung or a sari. We are taught to politely respect each other, but we aren’t necessarily inculcated with a sense of curiosity, which allows that respect to grow into stronger social bonds.

Second, Racial Harmony Day is looking more and more like an excuse to not talk about race. Issues like casual racism, discrimination in the army, or being unable to find apartments because of your race—these are lived experiences that have gained more and more attention in recent years, as more people speak up about what it’s like to be a minority in Singapore.

Yet race is still considered an OB marker, meaning that we often can’t have open conversations about it. Racial Harmony Day, then, can come across as somewhat absurd, because calls to celebrate ‘racial harmony’ don’t reflect the experiences of many minorities.

Playwright Alfian Sa’at has described how he feels “unsafe” as a minority; more recently, Umm Yusof spoke out about a children’s book he’d (ironically) borrowed for Racial Harmony Day, only to discover that it featured racist caricatures of minority Singaporeans.

None of this is new. From actor Shrey Bhargava’s public post about racism during movie auditions to outrage in response to brownface in a Nets e-Pay ad—none of these were widely accepted as racist incidents.

Instead of resulting in productive conversations about race, many of those who tried to confront these issues were accused of endangering Singapore’s social fabric.

Given all this, how then are we supposed to take Racial Harmony Day seriously?

Instead of fixating on how damaging the racial riots from 56 years ago were, we should be thinking about what race relations look like today. We should be looking to the future, and not remain obsessed with commemorating the past.

Singapore’s racial context has evolved. Racial Harmony Day might seem outdated if it doesn’t evolve to respond to what is arguably an even richer, more culturally vibrant Singapore.

Fourth, we need to incorporate these ‘difficult’ topics into our regular curriculum.

We must engage with ‘touchy’ questions about race from a young age; if kids are able to be open about their feelings, to articulate their confusion, or to ask questions without fearing they’ll be judged for it by their peers in the classroom, it helps to normalise the habit of having conversations about race and multicultural understanding outside the classroom as well.

In a recent visit to Tampines Secondary School, Education Minister Ong Ye Kung said: “We are encouraging all principals to hold more of such conversations in schools, not just during Racial Harmony Day, but do it as a normal course for CCE.”

It was an acknowledgement that it’s not just on Singaporeans to create a culture of openness when it comes to talk about race—it’s also on the government to implement race education early, to not only educate, but also inculcate a habit of having honest, productive discussions about difficult subjects.

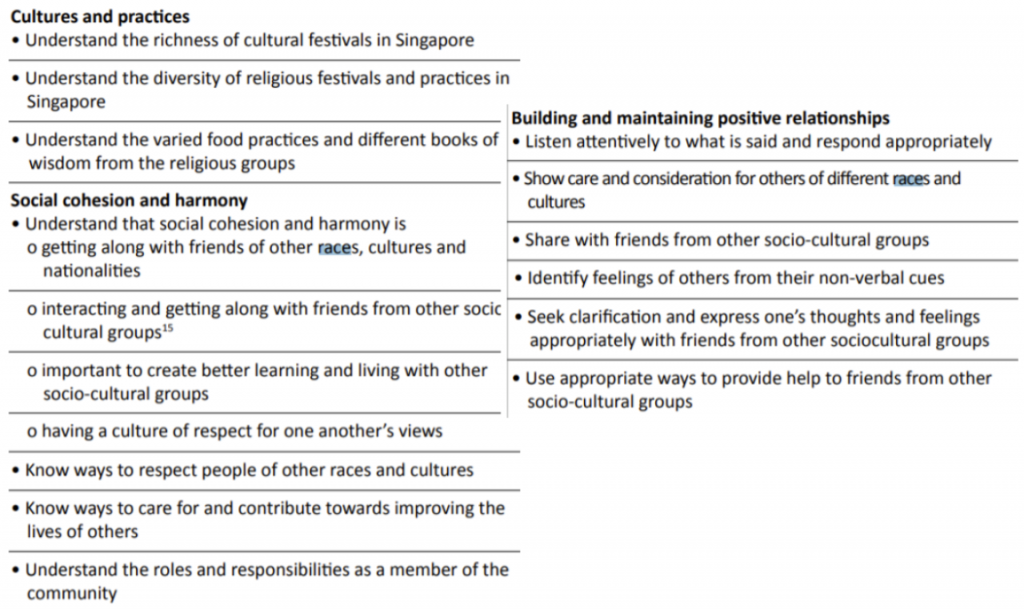

But it’s not enough to just “understand the diversity” of Singapore. The curriculum needs to be explicit about tackling racism and discrimination, instead of dancing around the issue.

For example, the curriculum can draw from actual incidents of racism in Singapore and show examples of what discrimination and microaggressions look like.

Finally, teachers must also be equipped with the appropriate skills to teach about race and Singapore’s postcolonial history, in the same way they need specific skills to teach any other subject, like Math or Science.

Trainers who specialise in Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion can be brought in to teach them how to create safe, productive spaces for discussion on a topic that has traditionally been treated as too sensitive or complex to be delved into at the primary or tertiary level.

The curriculum would also have to be forward-looking. For instance, students and teachers can brainstorm how to actively undo prejudices, moving the conversation on race forward.

In the end, race education has to teach students about Singapore’s present-day racial dynamics and how to navigate them. This can only be done if we have a holistic, comprehensive curriculum that is explicit about tackling race and discrimination.

We’ve mastered the art of appreciating each other’s cultures and celebrating multicultural diversity. Now we need to get better at educating our children on what our cultural histories, traditions, and practices mean.