When Singapore’s own circuit breaker began, I drew inspiration from them. I had a beatific vision that I, too, could not only survive the crisis, but make use of this sudden gift of time to become the Best Version of Myself.

I saw myself giving birth to a sourdough starter named “Molly”. Following one of those 28-day stay-home workout plans, I would transform my body from Christian Bale in The Machinist to Christian Bale in Batman Begins.

By the fifth day of the circuit breaker, I was lying in a foetal position on my exercise mat, my dog licking the single salty tear sliding off my cheeks.

Initially, I felt guilty for being so spineless. Then I remembered. I was at home trying to stay safe during a pandemic, not because I was taking an Eat Pray Love sabbatical of self-actualisation.

“Productivity” and “pandemic”, I realised, are two words that should never exist side by side.

As Alaa Hijazi, a trauma psychologist, writes:

This cultural obsession with [capitalistic] “productivity” and always spending time in a “productive” “fruitful” way is absolutely maddening.

Some people may find in productivity a shelter from the storm raging around us now. The certainties and predictability of, for example, baking—mix the wet ingredients with the dry, put the batter in a 180 degrees oven for one hour, and you will get a cake—are precisely what is lacking with the coronavirus. So it’s no surprise that people have been gravitating towards such projects.

Therefore, if you are tiding through the pandemic by throwing yourself into self-improvement, please, by all means, grab whatever keeps you afloat during this time.

But for the love of your deity of choice, don’t use your self-satisfied productivity to guilt-trip other people into feeling inadequate.

Here’s a quick refresher of the world we are still living in. At the time of writing, 1,919,913 people have contracted the coronavirus; 119,666 people have died. Because of the lack of ventilators, doctors in hard-hit countries have had to make decisions over who to save, and who to—for lack of a better word—sacrifice. People are losing jobs and the ability to support their families. Inequalities everywhere are being exacerbated because of the coronavirus: only 2000 frontline healthcare workers in the UK have been tested, but I’m sure a testing kit was personally sent to Boris Johnson the moment he had an itch in his throat.

We are, in other words, not luxuriating in the midst of a government-imposed holiday. We are struggling to come to terms with a vastly changed world, where children cannot see their grandparents for fear of transmitting an invisible virus to them and inadvertently sending them to the ICU.

And so on.

We are living through trauma. Hijazi describes it as such:

We are going through a collective trauma, that is bringing up profound grief, loss, panic over livelihoods, panic over loss of lives of loved ones. People’s nervous systems are barely coping with the sense of threat and vigilance for safety, or alternating with feeling numb and frozen and shutting down in response to it all. People are trying to survive poverty, fear, retriggering of trauma, retriggering of other mental health difficulties.

Frankly, under these circumstances, no one should give a shit as to whether you pick up Zoom yoga or learn about bitcoins during the month-long circuit breaker/lockdown/quarantine/stay-home notice.

And still, I’m beginning to feel overwhelmed, tired, depressed, by the coronavirus’s relentless bombardment on my mental health. As I was attempting to do some chest presses while lying on the floor, a sudden fatigue seized me and I just couldn’t move anymore.

It’s not just me. This feeling of Covid-19-related helplessness and exhaustion is as widespread as the disease, though it takes on different forms with different people.

The cult of productivity while working from home has taken its toll on one colleague: “Covid-19 has freed us from the prison of office culture, only to lead us into the greater prison that is paranoid self-surveillance—where you are constantly wondering if you’re being productive enough, as compared to your peers.”

Other friends are stressed by their own circumstances, but feel guilty about the stress because there are others who are suffering more than them: “You have to contend with the fact that your suffering is on a scale and it is not anywhere near the acute suffering of people in positions of severe economic/political disadvantage.”

“So you’re supposed to be a trooper. You’re supposed to do your best. Everyone is. You don’t get to grandstand about your struggle.”

But there is a mental toll that comes with suppressing your own feelings.

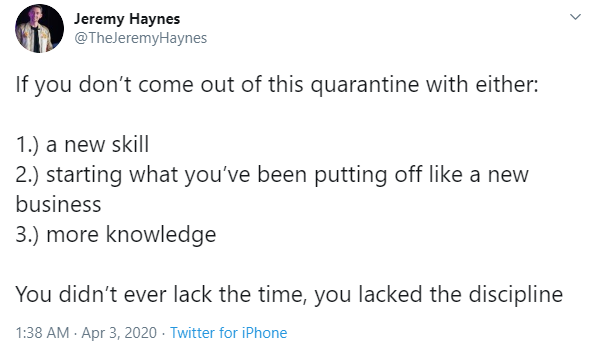

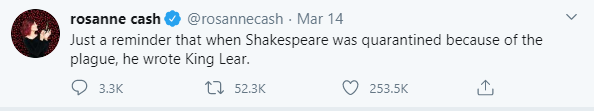

To shame people for not being productive—learn a new skill! a new language! improve yourself!—is plain cruelty.

In these times, staying sane is already an accomplishment. An achievement to celebrate. But if stability is not within grasp, that’s no worry either. Feeling as if you are losing it is, paradoxically, an indication that you are sane, a recognition that things are not normal but you will begin to process this new reality in your own time.

Allowing ourselves to experience this sense of uncertainty and coming to terms with what we can or cannot do during a crisis is, in my opinion, the most productive thing we can do for ourselves now.